For a large majority of business taxpayers and their in-house tax professionals worldwide, the Large Business & International Division (LB&I) of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) represents the principal point of regular interface with the U.S. taxing agency. Thus, any changes, whether large or small, in scope, focus, or operation will usually attract some measure of attention. In the present case, however, because the changes to LB&I represent a wholesale restructuring of its operations, the scrutiny from every corner of the business taxpayer and advisory communities has been intense. This article puts the current reorganization in a broader context, highlights specific structural and operational issues, and proposes practical solutions to the identified issues.

Background

On September 17, the IRS announced a major reorganization of LB&I. The reorganization is significant not only in its details but also in how relatively quickly it comes on the heels of the last reorganization in 2010, in which the former Large and Mid-Size Business Division (LMSB) was restructured and renamed LB&I with a renewed focus on international issues.

When LMSB “stood up” on June 4, 2000, its goals were laudatory. Its vision was “to be a world-class organization, responsive to the needs of customers in a global environment, while also applying innovative approaches to customer service and compliance.”1 The LMSB structure was aligned by industry (five groups with industry directors) instead of geography. The revised structure included 80 territory managers who were to “ensure that the appropriate resources are available to resolve issues referred by team managers,” who in turn were to manage the front-line examination process.2 This new “customer focus” was designed to “reduce examination costs and burdens” through new alternative dispute resolution (ADR) techniques, prefiling guidance, issue resolution, and new technology.3

The goals of the most recent reorganization, however, appear to be very different and reflect a very practical response to the environment in which the IRS currently finds itself (see box, IRS Woes: Changes Since 2000). In 2000, approximately 210,000 LMSB filers made annual cash payments of approximately $721 billion.4 Nearly ten percent of these taxpayers were examined each year, and LMSB had a staff of approximately 7,200.5 In 2010 LB&I administered the tax law for corporations, partnerships, and individuals with assets greater than $10 million with a staff of only about 6,000. Today, as in 2010, the IRS finds itself struggling to keep up with the rapid pace of globalization and its impact on the 296,000 taxpayers now within the jurisdiction of LB&I. Since 2010, however, the IRS’ budget has declined significantly and, accordingly, so have its resources. At the same time that the IRS has been asked to take on additional responsibilities, between fiscal years 2010 and 2015, the IRS’ budget has been reduced by more than $1.2 billion (ten percent; eighteen percent when adjusted for inflation).6 The IRS has significantly fewer employees, including fewer enforcement staff, and the number of audits and the amount collected from audits have shown a marked decline.

IRS Commissioner John Koskinen’s all too familiar refrain of “doing less with less” has begun to inform almost every decision the agency makes. One such decision: How to most efficiently allocate dwindling IRS examination resources and effectively enforce the tax laws.

Everything Old Is New Again

From a structural perspective, the most significant changes are the return to a single deputy commissioner rather than two (one domestic and one international)7 and the replacement of “industries” with nine practice areas.

The practice areas are each led by a director who reports to the deputy commissioner. The four regional practice areas are Western, Central, Eastern, and Northeastern, and the five subject matter practice areas are Pass-through Entities, Enterprise Activities, Cross-border Activities, Withholding and International Individual Compliance, and Treaty and Transfer Pricing Operations. Still unclear is how all of these practice areas will work together. LB&I Commissioner Douglas O’Donnell has indicated that more than one practice area may be involved in the audit of a taxpayer, but he has also indicated that the majority of LB&I’s now only 4,500 employees—sixty to seventy percent—will likely be assigned to one of the four regional compliance areas.8 These details are still being sorted out.

IRS Woes: Changes Since 2010

| Fewer Resources and Services | Additional Responsibilities |

| Funding cut 10% | Implement FATCA |

| At least 13,000 fewer employees (14% decline) | Implement ACA |

| Nearly 10,000 fewer enforcement staff (20% decline) | Increased number of identity theft cases |

| Lowest individual and business audit levels in a decade | |

| More than half of calls unanswered |

Sources: National IRS Taxpayer Advocate 2014 Annual Report to Congress; June 2015 GAO Report to Congress: “IRS Is Scaling Back Activities and Using Budget Flexibilities To Absorb Funding Cuts”; Prepared remarks of Commissioner John A. Koskinen before the Tax Policy Center

The “Campaign” Approach

Beyond the organizational chess game, the potentially revolutionary change is how the IRS proposes to identify issues (and presumably taxpayers) to be audited. For a number of years, LB&I has been talking about moving toward a more “issue-focused” approach for conducting examinations, advocating limited scope examinations for all taxpayers, and more recently instituting a requirement that information document requests (IDR) be issue-focused. More recently, there has been talk of phasing out the continuous audit program for most taxpayers and eliminating the CIC/IC distinction.

The proposed reorganization takes this approach to the next level, proposing that LB&I will identify potential areas of noncompliance and design “campaigns” to address them. Campaigns may involve a combination of “treatment streams,” including examinations, outreach, or guidance. LB&I acknowledges that it doesn’t really know what those campaigns may look like in the context of large business taxpayers, but it cites the Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program (OVDP) as an example of a campaign. Perhaps most significantly, agents will no longer be assigned returns and then be responsible for finding issues to audit. Rather, risk will be centrally assessed, and agents will be directed what to examine when they are assigned a return. As O’Donnell has acknowledged, this approach presents “complicated, cultural” challenges9 in an agency where agents have enjoyed relative autonomy for years.

A More “Agile” IRS?

A PowerPoint presentation announcing the rollout indicates that LB&I needs to “continuously evolve in order to keep pace with the way the world does business and with our taxpayers” and reflect “one LB&I,” instead of international versus domestic, field versus headquarters, and strategy versus execution. The materials also indicate LB&I will engage in “effective tax administration by updating examination processes that have not been refreshed for many years.”

The materials set out a “core set of guiding principles” that establish “the foundation for where LB&I wants to be in the future.” These are: (1) a flexible, well-trained workforce; (2) the selection of better work; (3) tailored treatments; and (4) an integrated feedback loop. The principles of enhanced training of agents and increased collaboration within the organization are laudable. However, as discussed below, these principles have little chance of translating into workable, sensible practices without the input of the taxpayer community. In that spirit, we proffer the following observations about opportunities and challenges with respect to each principle.

Flexible, Well-Trained Workforce

Desired outcome: Cultivate an environment of continuous learning to support a flexible workforce with focused training, foundational skillsets, specialized knowledge, and dynamic tools.

Opportunities and Challenges: A better-trained workforce is essential for the IRS to move into the twenty-first century. The International Practice Units published in recent months represent a step in the right direction in terms of training agents how to approach a particular issue, and the IRS is to be commended for its transparency in this regard. However, the IRS would also benefit from greater external input from taxpayers, through organizations such as TEI, that can best educate IRS agents regarding not only technical tax issues but also industry trends and other business decisions that drive behavior. With no sign of a significant increase in the IRS training budget any time soon,10 the agency should welcome some input from stakeholders. This training could be delivered via webinar in partnership with TEI and professional service providers. The audience from the IRS could include field, practice area personnel, and targeted national office employees. This training will give the IRS a taxpayer “point of view” around key issues, which should further productive discussions between taxpayers and the IRS.

The proposed reorganization takes this approach to the next level, proposing that LB&I will identify potential areas of noncompliance and design “campaigns” to address them.

Selection of Better Work

Desired outcome: Utilize data analytics and examiner feedback to identify better work with intended compliance outcomes.

Opportunities and challenges: The IRS does not hide the fact that for decades some returns have been selected for examination on the basis of computer scoring. Computer programs assign numeric scores to particular line items. The Discriminant Function System (DIF) score rates the potential for change, based on past IRS experience with similar returns. The Unreported Income DIF (UIDIF) score rates the return for the potential of unreported income. IRS personnel screen the highest-scoring returns, selecting some for audit and identifying the items on these returns that are most likely to need review.11 The algorithms themselves, however, are a closely guarded secret and change over time.12

What exactly the IRS has in mind for the twenty-first century (not to mention what resources it has available) in terms of data analytics is not entirely clear.13 A few public comments of IRS employees may shed some light on where the IRS is headed in this regard. For example, Jeff Butler, associate director of data management for the IRS Research, Analysis, and Statistics organization, was recently asked about the agency’s work in predictive analytics. In addition to the more obvious efforts to use data to combat ID theft and refund fraud, he explained a more interesting goal:

“The U.S. taxpayer population has some complexities that present unique challenges to the IRS. For example, high-wealth individuals often behave more like a business, and businesses with connected entities often look more like a group of interrelated economic structures than a single business. There is growing interest in network analysis and related methods as an exploratory approach to better understand these types of patterns.”14

This “network analysis” apparently has been applied to LB&I taxpayers. In June 2015, the IRS and the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center co-sponsored a tax administration research conference at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., where researchers from The University of Texas and the IRS presented “An Analysis of Flow-Through Entities Using Social Network Analysis Techniques.” The researchers measured various characteristics of roughly 6,000 enterprises that filed Forms 1120 in the 1120 LB&I taxpayer population for 2009 to determine “whether the ways that enterprises embed flow-throughs in their corporate structures facilitate noncompliance.”15

Previously, a computer scientist in the Intelligent Business Solutions group at the IRS Office of Research described a tool being developed to identify possible “abusive tax-avoidance transactions.” She provided an example of a taxpayer setting up an S-corporation to receive income from a partnership, thus avoiding the self-employment tax. The tool would enable an IRS agent to search for transactions in filings by entering a simple diagram of the structure of the transaction.16

It is likely that much of the IRS’ data analytics strategy will remain confidential, but these glimpses are revealing. Even assuming the IRS has the capabilities to perform and utilize meaningful data analytics, however, data analytics alone cannot effectuate meaningful enforcement. Consistent with our observations regarding training, the IRS would benefit from taking into account the feedback not only of examiners but also of taxpayers in defining intended compliance outcomes.

Tailored Treatments

Desired outcome: Employ an integrated set of tailored treatment streams to improve flexibility to address current and emerging issues and achieve compliance outcomes.

Opportunities and challenges: The operative word here is flexibility. This is perhaps where the IRS will have its greatest challenge: The changes it proposes will encounter a firmly entrenched culture in an agency where “agility” and “flexibility” are not the first words that come to mind. Flexibility will also require the IRS to recognize changes in taxpayer business models that may affect the way tax results are evaluated and reported. This could require the IRS to re-evaluate and possibly adjust long-standing audit positions. Because a number of tax issues are inherently fact-intensive, and because business is changing the way it manufactures, sells, and delivers its products and services, the IRS should be more open to understanding business models than before. In turn, taxpayers should be willing to make the investment with the field at the beginning of the audit to describe changes at its company since the previous audit.

Integrated Feedback Loop

Desired outcome: Drive continual collection and analysis of data and feedback to enhance ability to focus, plan, and execute work, and promote innovation and feedback-based improvement.

Opportunities and challenges: The IRS seeks to improve collaboration across all levels of the organization, which is commendable. Taxpayers are increasingly frustrated by a growing disconnect between the principles espoused by the national office and execution in the field. The IRS should strive for alignment on IRS audit positions between the field, practice area managers, and national office employees so that taxpayers are only audited once on an issue, as opposed to being exposed to multiple inquiries from various departments within the agency.

The Aspirational and the Practical

While many of the goals of the proposed reorganization are laudable, the proverbial devil will be in the details. IRS officials have indicated most taxpayers will not perceive a significant change in how their audits are conducted in the short-term, which provides scant comfort to taxpayers frustrated with the current process. The transition period is likely to be long, and without a clear delineation of roles and procedures, the reorganization is likely to fail. There are some recurring questions taxpayers would like to see resolved in the short-term.

Who’s In Charge?

IRS officials have indicated publicly that there will be no single member of the examination team with fifty-one percent of the vote in an examination, and the first point of convergence in the new organization structure is the deputy commissioner. Taxpayers need a single point of contact closer to the case who is empowered to make decisions as to when an issue will be considered resolved or abandoned. Being forced to elevate to the deputy commissioner is not desirable for several reasons. First, recent collective taxpayer experience indicates that there would be numerous occasions for such requests, which is not an efficient use of senior IRS resources. Second, the process of elevating to this level would likely contribute to further delays in resolving cases. Taxpayers are already frustrated with repeated requests for statute extensions. The IRS needs to understand that CFOs and audit committees expect tax departments to drive audits to conclusion within a reasonable amount of time. Having the IRS “disperse” its decision-making process throughout the organization is not congruent with the way in which taxpayers operate in their own organizations. Finally, as a practical matter, taxpayers are unlikely to want to elevate most issues to this level out of concern over the impact on the overall IRS relationship, resulting in reluctant acceptance of the status quo.

Although the role of the territory manager in the new structure is unclear, we propose that territory managers or their equivalent be retained and that there be a single such manager with tie-breaking authority assigned to each case. Today LB&I has only seventy territory managers, twenty percent of whom are performing in an “acting” capacity. These individuals are frequently where the buck stops when taxpayers need to elevate issues beyond their immediate team.17 Territory managers have served as an important safety valve when audits go astray and have been key (and more objective) decision-makers in both formal and informal mediations.18 For years the IRS has engaged in outreach efforts to encourage taxpayers to meet and confer with their territory manager. In any event, as noted, the introduction of multiple practice areas into an audit will only heighten the importance of a single point of contact to coordinate all of these moving parts.

Additionally, taxpayers should be aware of and have access to all decision-makers, specialists, and other advisers, including counsel, involved with their case. A growing concern among taxpayers has been the assignment of multiple specialists, counsel, issue practice groups (IPG), etc. to their cases, all operating on their own timetables with little apparent coordination. Still unclear at this time is whether under the reorganization, IPGs and international practice networks will remain intact or whether such specialists will be absorbed into the practice areas. However structured, specialists clearly will continue to play a role in the reorganized LB&I, and it is critical both that they be transparent to taxpayers and that territory managers have the authority and inclination to resolve any internal disputes on the team. In this regard we advocate that such managers receive both technical training and conflict resolution training.

When Will Our Examination End?

Taxpayers have also noticed an increasing trend of declining emphasis on estimated completion dates. It is even rumored that agents will no longer be measured on completions but rather on audit openings. This, coupled with the apparent intended autonomy of the various practice areas discussed above, leaves taxpayers potentially with little predictability as to when an audit might be resolved and the specter of unlimited requests for statute extensions. As noted above, tax departments are under increasing pressure—from the C-suite and audit committees—to achieve certainty sooner.

While the IRS has in the past shared the goal of achieving certainty sooner (see the discussion of the Compliance Assurance Process below), resource constraints seem to have shifted the focus to how best to allocate resources to meet immediate needs. For the reorganization to be successful in the long term, the IRS needs to think ahead to how and when resources it deploys today are redeployed. Examination teams should be charged with establishing estimated completion dates and making all reasonable efforts to close an examination by that date, even if it means abandoning an issue in some cases. In addition, where examination teams are unable to resolve an issue, after a concerted effort to use all of the dispute resolution tools at their disposal, they should be charged with facilitating moving cases to Appeals rather than delaying or completely blocking this avenue, which is occurring with increasing frequency.

Beyond the organizational chess game, the potentially truly revolutionary change is how the IRS proposes to identify issues (and presumably taxpayers) to be audited.

Do I Really Have To Respond to This IDR?

Overall, the new IDR process appears to have worked reasonably well for both taxpayers and the IRS. However, implementation has not been uniform. Many taxpayers, for example, have received IDRs that don’t define an issue or that define an issue too broadly. And, while activation of the enforcement process has been relatively infrequent, the increased possibility of summonses makes it all the more important that the original IDRs comply with the procedures now set forth in the IRM.

One area that should be addressed is the continued issuance of “any and all” IDRs. More specifically, the IRS should shift its focus from having taxpayers run extensive electronically stored information (ESI) queries to a more targeted IDR that focuses on the documents directly related to a transaction or an issue. Simply because taxpayers store much of their records today in an ESI form that is searchable should not be a basis for seeking documents that often are not directly related either to business purpose or the evaluation of the tax position. Additionally, these ESI searches produce such a large volume of documents, the taxpayer is left wondering if the IRS can meaningfully consume this material.

Similarly, many taxpayers continue to receive general books and records IDRs requesting large amounts of potentially irrelevant information even before the opening conference is held. If the reorganization works as described, in the long-term, IDRs presumably could be standardized for a particular campaign and more tailored to a particular taxpayer or industry than they are now. This merits a concerted focus by LB&I. In the interim, agents should receive ongoing training both in how to draft IDRs and what factors should be taken into consideration in establishing due dates and granting discretionary extensions.

My Company Is Under Continuous Audit Now — Should We Still Be Considering CAP?

The future of the Compliance Assurance Process (CAP) is one of the greatest uncertainties. Commissioner O’Donnell has suggested that CAP might not have a place in the new regime, noting that the reorganized IRS will be focused on noncompliant taxpayers, while CAP, which is resource-intensive, is a program designed for compliant taxpayers.19 Recently, some taxpayers looking to get into CAP for 2016 have been told that no new CAP taxpayers will be admitted in 2016. It is hard to imagine a world in which even the most cooperative taxpayers of a particular size are not audited at all by the IRS. The question then becomes: If not CAP, what is the right model for auditing large corporate taxpayers?

We should not lose sight of the benefits of CAP for taxpayers and the IRS alike. For taxpayers, CAP provides the benefit of certainty sooner. From the IRS’ perspective, CAP provides a real-time, in-depth experience of learning and understanding not only the current and emerging tax issues of CAP companies but also the business side of the industries participating in CAP. (Those industries include retail, financial services, insurance, medical devices, food services, hospitality, agriculture, pharmaceuticals, energy/utilities, transportation, media, and defense.) Any downsizing or elimination of CAP would certainly impact the IRS’ ability to more accurately assess risk within those industries and would also serve as a missed opportunity to extend the knowledge gained from the program to other LB&I taxpayers outside of CAP.

In addition, with the phase-out of the CIC program, taxpayers now under continuous audit are wondering what will happen to their ability to get penalty protection under Rev. Proc. 94-69 for disclosures made at the beginning of an audit. Presumably this needs to be replaced with another mechanism for taxpayers to voluntarily disclose needed changes to previously filed returns.

What Happened to Transparency and Collaboration?

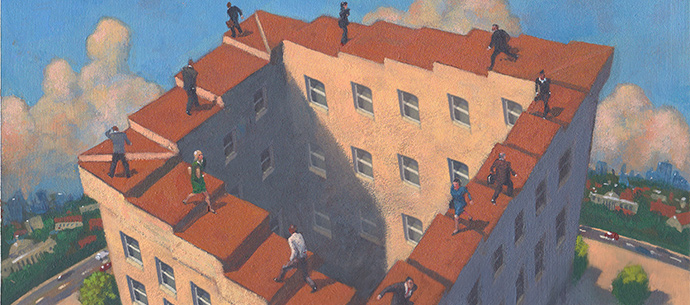

While shifting resources away from compliant taxpayers on the surface seems consistent with the goals of the reorganization, the suggested dichotomy between compliant taxpayers and noncompliant taxpayers is potentially troubling, even as LB&I professes to be focused on issues. We seem to be moving away from the principles of transparency and collaboration that informed initiatives such as CAP and Schedule UTP to a more adversarial “us versus them” system. Even the use of the term “campaign” suggests a military style assault on perceived tax noncompliance.20 We posit that the pendulum perhaps has begun to swing too far from the customer focus that characterized the LMSB stand-up in 2000. In fact, the IRS is no longer even paying lip service to the principle of resolving issues at the lowest possible level, or at least certain parts of the organization are not.

In this regard, taxpayers have noted with some trepidation recent highly publicized examples of the IRS using increasingly aggressive tactics, particularly in transfer pricing audits, to obtain information and keep statutes open, with an apparent view toward setting certain cases up for litigation as opposed to resolving issues at the lowest possible level. These include: (1) designating cases for litigation, thus precluding access to Appeals;21 (2) issuing designated summonses, which suspend the statute of limitations;22(3) summarily issuing a statutory notice of deficiency (ninety-day letter) with no prior thirty-day letter; and (4) retaining outside legal counsel to conduct examination activities.23

The IRS’ current process for designating cases for litigation in particular arguably does not fit within the framework of the reorganization’s focus on issues—the IRS’ process permits designation of a particular taxpayer’s case for litigation even while the identical issue for another taxpayer is allowed to be settled at Appeals. Similarly, taxpayers have found their access to Appeals blocked—unjustifiably so, they believe—or at least delayed when the clock starts to run out in a complex examination and the IRS resorts to designated summonses or summary ninety-day letters. The use of outside counsel in examinations (and the hasty after-the-fact issuance of temporary regulations to permit this) is particularly troublesome. Not only does retaining outside counsel in an examination contribute to an increasingly adversarial environment, but it also puts sensitive and confidential taxpayer information at risk.

One can surmise that the dollars at stake in these cases are at least in part responsible for this “play to win” mentality, but it can be unfair to the particular taxpayer and provides little predictability to others with similar issues who fear being forced into expensive and protracted litigation. While the efficient use of IRS examination resources is in part behind the changes announced in the reorganization, skeptical taxpayers with certain significant issues are left wondering whether they will be forced to choose between full concession and litigation. Appeals should remain a viable and meaningful option for most tax issues, and the IRS’ ability to extend an audit to develop a case for litigation should be limited. Taxpayers should not have to pay the price for the IRS’ resource constraints, regardless of the dollars involved.

The Path Forward: Crowdsourcing the Solutions

LB&I examination procedures contained in the Quality Examination Process (QEP) have been under revision for nearly two years. In 2014, a draft of a new Publication 5125 made it into the public domain, apparently unintentionally. The QEP was itself an outgrowth of a collaboration between LMSB and TEI that resulted in the Joint Audit Planning process. In recent years, taxpayers have had less opportunity to have input into the process. Draft Publication 5125 needs to be reworked and finalized to provide a concrete and workable framework around roles, responsibilities, milestones, and expectations in audits conducted by the reorganized LB&I, ideally with taxpayer input.

In this era of crowdsourcing, LB&I reforms will be most effective with the input of the taxpayer community. Many of the details of the reorganization are left to be filled in, but challenges taxpayers are currently experiencing with IRS audits are at risk of only being exacerbated if LB&I leadership listens only to its internal feedback loop. The reorganization of LB&I provides an ideal opportunity for the IRS to work with TEI, taxpayers, and practitioners to update and finalize revisions to the examination process that further our common goals. We hope they take us up on this offer.

Elizabeth Askey is a tax principal at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. Michael Bernard is U.S. tax counsel at Microsoft Corporation. Jean Pawlow is co-chair of the tax controversy practice at McDermott, Will & Emery. The views expressed herein are their own and do not necessarily represent those of their employers.

Endnotes

- Larry R. Langdon & John Dalrymple, Developments in the Reorganization of the Internal Revenue Service, Administrative Law Review, Vol. 53, No. 2 (Spring 2001), p. 641.

- “Modernizing America’s Tax Agency, IRS Organization Blueprint 2000,” available at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/27877d00.pdf.

- Id. at 648. Examples of new ADR developments included: a new Pre-Filing Agreement program (piloted in 2000 and made permanent in Jan. 2001), see Rev. Proc. 2001-22, 2001-9 I.R.B. 745; a new Fast Track Settlement program (piloted in Nov. 2001 and made permanent in 2003), see Notice 2001-67, 2001-2 C.B. 544 and Rev. Proc. 2003-40, 2003-1 C.B. 1044; and an extended and expanded post-Appeals mediation program, see Announcement 2001–9, 2001–1 C.B. 357, and Rev. Proc. 2002–44, 2002–2 C.B. 10. The IRS also spent more than three years on the design and development of a corporate e-file program culminating in temporary regulations issued Jan. 11, 2005, and final regulations issued Nov. 13, 2007, (TD 9363), requiring corporations with $10 million or more in total assets and that file 250 or more returns a year to electronically file their Form 1120 or 1120S.

- LMSB initially was responsible for corporations, Subchapter S corporations and partnerships with assets greater than $5 million.

- Id. at 641 and 643.

- www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2015reports/201530035fr.pdf.

- The move to a single deputy commissioner may have been in response to what some perceived as tension between the domestic and international arms of LB&I. See, e.g., Jaime Arora, Amy S. Elliott, & Andrew Velarde, Major Shake-Up at LB&I? Tax analysts, July 3, 2014. In addition, both former Director of Transfer Pricing Samuel Maruca and former Deputy Commissioner (International) Michael Danilack spoke frequently about the challenges involved in integrating transfer pricing experts into field operations, particularly in light of the increasingly tight resources. See, e.g., Tax Executives Institute, Minutes of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue and Large Business & International Division Liaison Meeting, June 4, 2014, www.tei.org/Documents/Final%202014_CIR-LBI_minutes.pdf.

- Amy S. Elliott, CAP Real-Time Audits May be Inconsistent with New LB&I Strategy, Tax Notes Today, Nov. 4, 2015, Doc:2015-24395.

- Id.

- The IRS training budget declined 83 percent between 2010 and 2014. National Taxpayer Advocate 2014 Annual Report to Congress at 16.

- www.irs.gov/uac/The-Examination-(Audit)-Process.

- David Cay Johnston, Your Taxes: Some New Tricks To Help Filers Avoid an Old Audit Trap, The New York Times, Feb. 25, 1996, www.nytimes.com/1996/02/25/business.

- See, e.g., National Press Club, Prepared Remarks of John A. Koskinen, Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, Washington, D.C., March 31, 2015 (“We are operating with antiquated systems that are increasingly at risk, as we continue to fall behind in upgrading both hardware infrastructure and software. … We have many applications that were running when John F. Kennedy was President”).

- www.predictiveanalyticsworld.com/patimes/wise-practitioner-predictive-analytics-interview-series-jeff-butler-at-irs-research-analysis-and-statistics-organization09022015/6243.

- www.irs.gov/uac/SOI-Tax-Stats–2015-IRS-TPC-Research-Conference.

- http://data-informed.com/irs-implements-analytics-for-compliance-fraud-detection-and-workforce-management.

- See IRM 4.51.1 Rules of Engagement.

- See, e.g., Michael Gregory, How to Work with IRS Management to Resolve IRS Field Specialist Issues, Tax Executives Institute.

- Amy S. Elliott, CAP Real-Time Audits May be Inconsistent with New LB&I Strategy, Tax Notes Today, Nov. 4, 2015, Doc:2015-24395.

- A “campaign” is frequently defined as “a series of military operations undertaken to achieve a large-scale objective during a war,” www.thefreedictionary.com/campaign. The choice of imagery is interesting and quite different from the tone and tenor of LMSB’s formation.

- Kelly Phillips Erb, Coca-Cola Says IRS Wants $3.3 Billion In Additional Tax Following Audit, www.Forbes.com, Sept. 18, 2015; Dolores W. Gregory, “IRS Joins Amazon in Request for Judge, Saying Case Designated for Litigation,” https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/wp-content/pdf/transfer-pricing/IRS-Joins-Amazon-In-Request-For-Judge.pdf.

- Dolores W. Gregory, Transfer Pricing Practice Has Strengthened IRS’ Hand in Section 482 Cases, Ralph Says, BNA Transfer Pricing Report, May 28, 2015; see also Marie Sapirie, “Former Territory Manager Describes Transfer Pricing Changes,” 2015 TNT 103-5 (May 29, 2015).

- Alison Frankel, “Judge in Microsoft Tax Case to Decide If IRS Improperly Hired Quinn Emanuel,” http://blogs.reuters.com/alison-frankel/2015/06/18/judge-in-microsoft-tax-case-to-decide-if-irs-improperly-hired-quinn-emanuel.