Never before has international taxation been in such a spotlight in the business press. Cross-border mergers, international tax policy, and base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) have each been the subject of major front-page articles in the financial news. Over the last two years another topic has increasingly been in focus: the “state aid” cases being brought by the European Commission (EC) against various European Union (EU) member states with respect to tax rulings issued by those member states to multinational corporations.

EU state aid is a European concept that prohibits EU member states from providing impermissible aid to companies, which, as these cases have demonstrated, may be in the form of tax treatment or benefits. The notion of a government providing improper tax benefits may remind U.S. tax practitioners of the debate between the United States and the World Trade Organization (WTO) relating to whether the United States was providing an export subsidy to manufacturers by means of the foreign sales corporation (FSC) regime.1 The WTO eventually found that the FSC regime provided such a subsidy. But the WTO’s challenge to the FSC regime focused on trade law, while the state aid challenges are based on competition and European internal market law. Additionally, the WTO struck down the FSC regime as itself inappropriate. Here, the EC is focused both on the legitimacy of a tax regime itself and on how the regime is being applied—for example, through the issuance of tax rulings such as advance pricing agreements (APAs)—by the EU member state in a manner that the EC considers to distort competition.2

The recent state aid cases represent the first time the EC has exercised state aid control to address corporate tax practices on an EU scale.3 If the EC is successful, companies that received these rulings and APAs may be forced to repay up to ten years of “tax savings” to the very EU member state that granted the ruling in the first place. As discussed below, one key question for multinationals is the degree to which the EC will challenge rulings, APAs, and, potentially, settlements with various EU member states. A multinational may have hammered out the terms of a ruling or APA with a country such as the Netherlands or Ireland years or even decades ago and, having followed its terms, used the APA as a basis for further tax planning. The actions of the EC might well now upend that planning on a retroactive basis, with consequences beyond anything a taxpayer might have considered possible under the typical challenges a multinational faces due to having tax years that remain open under the relevant statute of limitations.

Moreover, the EC has made clear its state aid investigations are focused not just on whether a ruling or APA process itself constitutes state aid but also on whether the substantive tax treatment applied to particular taxpayers constitutes state aid. This raises the question of how far the EC’s actions might go. Would the EC review settlements between taxpayers and an EU member state, other tax cases in the EU, or even simply informal agreements reached between taxpayers and a taxing jurisdiction in the course of day-to-day compliance and examinations? The audit of a recurring issue between an EU member state and Taxpayer A may have resulted in a détente between the two on how to treat the particular intercompany pricing of an item.4 Are those types of settlements, based in part on substantive tax issues and, as is often the case, in part on the mutual administrative benefits of settling audits and providing consistency to the taxpayer and the tax examiner, now subject to EC challenge?

This article outlines the historical background of the state aid issue and the technical process behind the recent EC actions. While there has been considerable attention in the press and seminar circuit on the various EC cases and the specific companies involved, the focus here is on the general issue of EU state aid as applied by the EC to tax rulings and APAs, along with the EC’s overall initiative. Included are brief and high-level summaries of two published EC cases and the rulings at issue, merely to illustrate the type of routine rulings under EC scrutiny. Summaries of the various reactions to the EC’s initiative follow, including very strong responses from Congress and the U.S. Department of the Treasury. The conclusion discusses the potential for obtaining a U.S. foreign tax credit for amounts paid a result of state aid decisions.

Key Questions and Actions for Multinationals

The corporate and adviser communities and the U.S. government will continue to watch the unfolding actions initiated by the EC. As discussed below, while one cannot consider the use of state aid in a tax context unprecedented, there is no doubt the last two or three years have seen a relatively new phenomenon of EU-wide targeting of seemingly routine tax rulings and APAs. There is no set playbook for the taxpayer community to handle state aid investigations, unlike in the case of a typical EU member state tax audit.

The best that a taxpayer and its advisers can do as these cases continue to unfold may be to:

- Continue to monitor where the EC is focused.

- Assess the status of all current rulings, APAs, and other formal or informal agreements with EU member states over tax issues.

- Assemble documentation as best as possible to support the correctness of the actions taken by the EU member state.

- Continuously determine with the help, if available, of an EU member state whether any such agreement or ruling is the subject of an EC investigation. Unfortunately, there may not be a set process or obligation of the member state to do so.

- Intervene before the EC, to the extent that a ruling or agreement is being investigated, represent its own position and, to the greatest extent possible, advocate for the correctness of the EU member state’s actions. This will both support the original positions taken and, as importantly, demonstrate that any eventual payment by a taxpayer under an EC decision was made after seeking all effective and practical remedies.5

Historical Background on Application of State Aid in Tax Context

Pre-2012 Application of State Aid Control to Tax Issues

State aid law prohibits EU member states from granting aid in a manner that distorts competition and the European internal market.6 The application of state aid control to tax issues represents a unique intersection between competition law and tax law and is likely new for many U.S. tax practitioners. There appears to be no direct parallel in domestic U.S. law.

As the broad description of state aid law suggests, state aid control is by no means geared solely toward tax regimes or practices.7 Over the decades, the EC has examined whether various EU member state actions have constituted impermissible state aid in a wide variety of areas such as transport, energy, and agriculture. In a more traditional direct economic benefit situation, the EC has routinely assessed and approved aid for the purposes of coordinating the transport and shifting of freight from road to rail, such as by providing incentives for private investment.8

The application of state aid rules to tax law is built upon the concept that a reduced tax burden may constitute an impermissible advantage provided by an EU member state to a beneficiary. The EC, the sole body charged with state aid enforcement, has in the past applied its authority to challenge an EU member state’s tax regime or a specific application of the tax regime as anticompetitive when it provides a “selective advantage” to certain taxpayers.9 The EC has found that tax measures can provide an “advantage” because the “loss of tax revenue is equivalent to consumption of State resources in the form of fiscal expenditure.”10

Recent Focus of State Aid Control to Tax Rulings

While the EC has in the past used state aid control to address individual EU member state tax issues,11 recently the EC has begun to rely more heavily on state aid to address tax practices it perceives as harming the distribution of tax revenues among the member states. After the Great Recession, in a period of tight public budgets and sluggish growth, the EC considered its two options to attempt to reduce the effects of a lack of unified tax treatment of company profits throughout the EU: tax harmonizing legislation (which requires unanimity by the EC and thus is very difficult to reach) or state aid control (for which the EC has exclusive competence). As described below, the EC has begun focusing on the latter option while continuing to pursue options for introducing tax harmonizing legislation.

On December 6, 2012, the EC laid the framework for using state aid to challenge tax rulings when it issued two formal recommendations: one on “aggressive tax planning,” which it described as “taking advantage of the technicalities of a tax system or of mismatches between two or more tax systems for the purpose of reducing tax liability”12 and the other regarding “measures intended to encourage third countries to apply minimum standards of good governance in tax matters.”13 The latter recommendation explained that a number of tax measures “are subject to scrutiny under the rules on state aid.”14 The EC has also stated its concern that some rulings may be misusing international tax treaties to permit double nontaxation: “The purpose of Double Taxation treaties between countries is to avoid double taxation—not to justify double nontaxation.”15

In February 2014, the EC launched an inquiry into the tax rulings practice of six EU member states: Luxembourg, Ireland, the Netherlands, the UK, Cyprus, and Malta. Joaquín Almunia, then commissioner for competition, stated that “[a] limited number of companies actually manage to avoid paying their proper share of taxes by reaching out to certain countries and shifting their profits there. In those cases, where national laws or tax-administration decisions permit or encourage these practices, there might be a state aid component involved and I intend to go to the bottom of it.”16

The application of state aid rules to tax law is built upon the concept that a reduced tax burden may constitute an impermissible advantage provided by an EU member state

to a beneficiary.

In March 2014, the EC requested information from Luxembourg regarding its tax ruling system and intellectual property tax regime “in order to assess whether certain tax practices favour certain companies, in breach of EU state aid rules.”17 Also in March 2014, the EC issued a draft notice on the notion of state aid, which indicated that the EC would focus on tax rulings that are discretionary, are not available to all taxpayers, treat one taxpayer more favorably than similarly situated taxpayers, or contradict applicable tax law. 18 The EC extended its inquiry to tax rulings of all other EU countries in December 2014.19

The EC’s review of the rulings obtained resulted in the opening of formal state aid investigations against several EU member states. The EC ruled against the Netherlands and Luxembourg in two final decisions released on October 21, 2015.20 A number of these investigations still remain outstanding, including another investigation against Luxembourg announced on December 3, 2015.21

The EC has also recently challenged an entire tax ruling regime: the Belgium “excess profit” tax ruling system. The “excess profit” ruling system allows a company to request a ruling that would determine its tax liability in part by determining the amount of “excess profits,” or profits that result from being part of a multinational group. The EC began a state aid investigation on February 3, 2015, on the basis of information requested from Belgium.22 The EC challenged the regime on the basis that the system “appears to grant substantial tax reductions only to certain multinational companies that would not be available to stand-alone companies.”23 The EC issued its final decision on January 11, 2016, concluding that the tax regime was illegal under the state aid rules and ordering Belgium to recover some €700 billion ($763 billion) from the thirty-five companies that had obtained rulings on the basis of the “excess profit” system.24

These EC decisions will likely face challenges from the EU member states in the EU General Court under the process described below.

The EC’s Process of Applying State Aid to Tax Regimes

Investigation and Opening Decision Process

A state aid investigation may arise from notification to the EC of a measure constituting state aid by an EU member state, from a complaint, or of the EC’s own initiative, as is the case for the recent investigations relating to tax rulings.25 The recent tax ruling investigations have primarily resulted from the EC’s inquiry into the EU member states’ rulings, which commenced as described above. With the exception of the Belgium “excess profit” ruling system, the EC has not challenged the overall ruling regimes themselves but has instead challenged specific tax rulings.26 Because EU member states have not generally contemplated the possibility that individual rulings or ruling systems would constitute state aid, the EU member states have generally not notified the EC of their rulings or tax ruling system. Note that the lack of notification may be raised by the EC when the EU member state and the alleged state aid beneficiaries (that is, the taxpayers) argue that they relied on the legality of the tax measure under national law.27

The EC begins a formal investigation by issuing a published decision that sets forth a preliminary assessment of whether the ruling at issue constitutes state aid.28 The EU member state may submit comments to the decision, usually within one month.29 The taxpayer at issue may also participate in the investigation, but, to be clear, the EC’s investigation is against the EU member state rather than the taxpayer.

In investigating the state aid claims, the EC must determine whether the EU member state provided a “selective advantage” to a company in the form of a tax benefit or subsidy. The following criteria, first listed in the EU Treaty of 195730 and subsequently in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (the EU Treaty),31 are used to determine whether a public measure, such as the tax rulings and regimes at issue, constitutes state aid:32

- A tax measure under consideration must confer on recipients an advantage.33

- Such advantage must be granted by the state or through state resources.34

- Such measure must affect competition and trade between EU member states.35

- Such measure must be specific or selective.36

Final Decision and Recovery Process

After completing its investigation, the EC will issue a final decision to the EU member state. If the EC considers that state aid exists and that it is “incompatible,” in the sense that it does not correspond to any of the common European objectives indicated by the EU Treaty, then the EU member state is required to recover the state aid.37 When striking down rulings as state aid, the EC may estimate the amount of the aid, but the precise amounts must be determined by the EU member state on the basis of the methodology set forth in the final decision.38 The EU member state will thereafter calculate the amount of aid and recover such amounts from the taxpayer who had received the ruling. If an EU member state or taxpayer seeks an appeal, the EU member state must still seek recovery, but the taxpayer might be able to make the payment to a blocked bank account while the appeal is ongoing.39

Appeal Process

Although an EC final decision would be issued against the EU member state itself, an EU member state, the beneficiary of the state aid (i.e., the taxpayer), or other interested parties may challenge the validity of EC decisions on state aid before the EU General Court in the first instance.40 The judgment of the EU General Court may be appealed to the European Court of Justice for review of legal issues only (i.e., not factual issues). As such, the EU General Court and the European Court of Justice will review the legality of the state aid decision and may annul such decision.41

According to EU Courts, taxpayers who have received a tax ruling that has been determined to be state aid in a final decision issued by the EC must challenge the final decision in order to preserve the right to contest the EU member state’s recovery order before that member state’s national courts.42 Regardless of whether the taxpayer challenges the final decision, the EU member state must still calculate the amount of the state aid it must recover, which provides an additional opportunity for taxpayer advocacy. In these types of cases, where the state aid arises from the use of allegedly improper transfer pricing methodologies, the EU member state must apply the EC-sanctioned transfer pricing methodology to the taxpayer to determine the amount of state aid it must recover. That process must to some degree involve the taxpayer’s cooperation to determine the recovery amount.

The EU appeal process can be rather lengthy. For example, the European Court of Justice recently overruled the EC’s final decision in the Spanish financial goodwill amortization cases.43 The EC opened its investigation in 2007 and issued final decisions in 2009 and 2011 stating that the Spanish measure constituted unlawful state aid. However, it was not until 2014 that the EU General Court annulled both the 2009 and 2011 EC decisions.

Examples of Recent Tax Rulings and EC Challenges to Rulings

The following is a summary of two published EC cases and their description of the tax rulings issued to two large multinationals.44 These summaries provide examples of the types of rulings under EC scrutiny.

In challenging these rulings, the EC alleges improper transfer pricing analyses and conclusions by the EU member state. In effect, the EC appears to be substituting its own interpretation of OECD transfer pricing guidelines for those of the EU member state. It is noted that the two published EC decisions are quite lengthy and detailed.

Example 1

Example 1

In its decision opening the formal investigation,45 the EC first outlined several general concepts of taxing multinational enterprises and the basis for transfer pricing rules, notably the “arm’s length principle” as set forth in Article 9 of the OECD Model Tax Convention. The EC then provided the following factual summary.

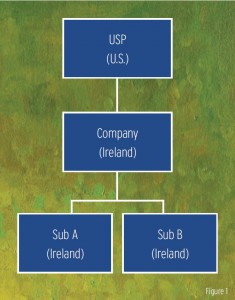

U.S. parent (USP) was a large U.S. public company with operations in various countries including Ireland. An abbreviated summary of the entities at issue are set forth in Figure 1.

USP held two Irish incorporated but non-Irish resident subsidiaries (Sub A and Sub B), each of which had an Irish branch. In 1991, Ireland issued an APA providing that the profits attributable to the Irish branch of Sub A should be calculated as sixty-five percent of operating costs (for the amount of expenses up to $60 million) and twenty percent of operating costs (for the amount of expenses in excess of $60 million). The APA also provided that profits attributable to the Irish branch of Sub B should equal twelve and a half percent of all operating costs.

The APA was updated in 2007 to state that the Sub A Irish branch should have a margin of ten to twenty percent of branch operating costs plus one to nine percent of branch turnover (the latter being considered an appropriate return on IP) and that the Sub B Irish branch should have a margin of eight to eighteen percent of branch operating costs.

The EC challenged the APAs as impermissible state aid that provided a selective advantage to the ruling recipient primarily on the basis that it “is of the opinion that the contested rulings do not comply with the arm’s length principle” central to the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines.46 The EC made a number of allegations with respect to the APAs, including:

- The APAs were negotiated instead of substantiated by reference to comparable transactions.

- The EU member state did not provide a transfer pricing report to the EC to support the 1991 APA.

- The EU member state did not provide an explanation of why the particular transfer pricing methodology was accepted by the EU member state.

- The transfer pricing methodology contained inconsistencies.

- The 1991 APA had no expiration date and was applied for fifteen years without change.47

It is noteworthy that the EC makes the point that:

If, instead of issuing a ruling, the tax administration simply accepted a method of taxation based on prices which depart from conditions prevailing between prudent independent operators, there would also be State Aid. The main problem is not the ruling as such, but the acceptance of a method of taxation which does not reflect market principles.48

This statement raises the question of whether, in another case outside the context of a ruling or APA, the EC might challenge a settlement of a tax dispute. In other words, the EC has apparently substituted its judgment for the manner in which the EU member state government determined the taxable income of a taxpayer. So, presumably, that substitution might be applied outside the context of a ruling or APA.

This EC case is still ongoing.

Example 2

Example 2

In its decision opening the formal investigation,49 the EC similarly first outlined several general concepts of taxing multinational enterprises and the basis for transfer pricing rules, notably the “arm’s length principle” as set forth in Article 9 of the OECD Model Tax Convention. The EC then provided the following factual summary:

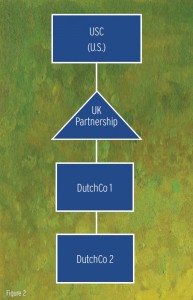

U.S. parent (USC) was a large U.S. public company with operations in various countries including the Netherlands and the UK. An abbreviated summary of the entities at issue are set forth in Figure 2.

UK Partnership had entered into a cost-sharing agreement with USC to develop IP. UK Partnership licensed that IP to DutchCo 1, which sublicensed the IP to various EU related and unrelated distributors. UK Partnership also licensed IP to DutchCo 2 to allow the latter to engage in certain manufacturing activities. The product manufactured by DutchCo 2 was then sold to related and unrelated distributors.

The Netherlands issued an APA to the group providing that the manufacturing profit margin for DutchCo 2 should equal a markup of between nine to twelve percent of DutchCo 2’s total costs, less costs for raw materials. This was based on the transactional net margin method (TNMM) with certain adjustments. The APA provided that the remaining profit of DutchCo 2 should be paid as a royalty to UK Partnership. According to the EC, this royalty was not taxed in the UK, due to UK Partnership’s fiscal transparency under UK law.

The EC challenged the Netherlands APA as constituting state aid primarily on the basis that the APA violated the arm’s-length principle under OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines. The EC provided a lengthy description of what it viewed as inappropriate assumptions and factors considered in the transfer pricing analysis. The EC made several allegations, including the following, with respect to the APA:

- “Questionable adjustments” were made to the TNMM to achieve the nine to twelve percent markup, which had the effect of lowering the resulting corporate income tax basis in the Netherlands.50

- The royalty rate for use of the IP had no actual bearing on the value of the IP.

- The EC “questions the economic rationale” for DutchCo 2 to surrender functions and risks normally undertaken by manufacturing companies in the same field that would lead to a higher return.51

The EC ultimately decided on October 21, 2015, that the APA constituted state aid, effectively overruling the EU member state’s interpretation of OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines.52

Reactions to EC Investigations and Decisions

Reactions by EU Member States

Luxembourg and the Netherlands53 have both appealed the decisions issued by the EC in October 2015. Luxembourg stated that, while it is committed to combating abusive tax practices, “[t]he vast majority of EU member states use tax rulings to provide legal certainty for the taxpayer.”54 The Netherlands also stated its support in fighting tax avoidance, including amending Dutch legislation and treaties where necessary, but maintained that it followed OECD transfer pricing guidelines.55 The Netherlands also criticized the EC’s approach as causing confusion and uncertainty in the proper application of transfer pricing rulings.56 Belgium has announced it will appeal the EC’s decision relating to its “excess profits” ruling regime.57

Reactions by the United States

The reaction to the EC actions from various policymakers, business groups, and academic scholars in the United States has been sharp and almost universally critical.

In a December 2014 letter, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce told the EC that the investigations place U.S. businesses in a position where they are “caught between EU treaty provisions that on one hand leave member states to govern their own direct taxation laws while on the other hand provide the European Commission competency to enforce state aid laws.”58 The letter went on to say that “competition enforcement is not the appropriate means through which to settle what is fundamentally a policy debate rather than a competition violation.”59 In a separate statement regarding the October 2015 EC decisions against Luxembourg and the Netherlands, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce noted that the decisions “inject a significant degree of uncertainty into the business climate, retroactively calling into question thousands of tax arrangements that were previously understood to be legal and appropriate.”60

Some scholars have been equally critical. A December 2015 Wall Street Journal piece by a longtime and frequent commentator on tax issues and policy criticized the EC’s actions.61 The author notes that taxpayers reliance on national governments’ representations and written rulings are to “no avail” given the subsequent actions by the EC, and that the process by which the EC determined the amounts owed by these companies “does not pass the smell test” to a U.S. lawyer steeped in due process and the rule of law. Moreover the author appears to point out the irony that, pursuant to the EC’s actions, the EU member states that issued the rulings would “astonishingly” get to keep the amounts at issue in the EC’s decisions. Finally, the author notes that the practical consequence of these actions by the EC may result in an offset to U.S. taxes.62

The Netherlands also criticized the EC’s approach as causing confusion and uncertainty in the proper application of transfer pricing rulings.

U.S. government officials have also weighed in with several concerns, including the disproportionate targeting of U.S. multinationals and the potential loss of U.S. tax revenue. In December 2015, in a combination of congressional testimony and public statements, Robert Stack, deputy assistant secretary for International Tax Affairs for the U.S. Treasury, criticized the EC’s role as “final arbiter”63 of transfer pricing issues, as it may “potentially undermine our rights under our tax treaties” because the “EU Commission is in effect telling member states how they should have applied their own tax laws over a ten-year period.”64 Stack noted that four of the five companies involved in ongoing investigations at that time were U.S. multinationals65 and that “EU Commission appears to be disproportionately targeting U.S. companies.”66 While Stack stated that “the IRS and Treasury have not yet analyzed the equally novel foreign tax credit issues raised by these cases,” he said that “it is possible that the settlement payments ultimately could be determined to give rise to creditable foreign taxes [and] U.S. taxpayers would wind up footing the bill for these state aid settlements.67 Stack has also recently met with the EC in person to personally express these views.68

In January 2016, a bipartisan group of senators wrote to the Treasury regarding the investigations.69 The senators praised Treasury’s efforts in communicating U.S. concerns to the EC, but went on to say that it “alarms us, however, that the EU Commission is using a nontax forum to target U.S. firms essentially to force its member states to impose taxes, looking back as far as ten years, in a manner inconsistent with internationally accepted standards in place at the time.”70 Because of this potential discrimination, the senators encouraged the Treasury to consider “whether corporations of the United States are being subjected to discriminatory or extraterritorial taxes” within the meaning of section 891 of the Code.71 Section 891 would double tax rates imposed on citizens and corporations of a foreign country that the president finds is imposing discriminatory taxes on U.S. citizens or corporations.

U.S. Tax Implications

As noted above, scholars, the Treasury, and Congress have directly and indirectly spoken about the issue of U.S. foreign tax credit (FTC) eligibility with respect to any amounts that may ultimately be paid to a member state pursuant to the actions of the EC. In the event that an EC state aid investigation results in an EU member state recovering amounts from the beneficiary of the state aid (i.e., the company that received the subject ruling), the question remains whether such payment will constitute creditable taxes under the Code and applicable Treasury regulations. While FTC eligibility is a complex issue,72 the fundamental questions regarding such eligibility are likely (1) whether any payment to an EU member state meets the definition of an “income tax” and (2) whether the taxpayer has exhausted all effective and practical remedies to reduce the amount of the tax payable.73

The state aid cases involve the EC imposing its determination on the proper application of OECD transfer pricing rules upon the EU member state. In effect, the EC is telling the EU member state to adjust the tax base to which the member state’s otherwise applicable corporate tax regime would apply under the member state’s domestic tax law. Because the amounts paid by taxpayers as a result of the EC state aid decisions would essentially be based on the same statutory levy imposed by the member state prior to the income reallocation mandated by the EC decision, there is no reason why such payments would not meet the definition of “income tax.” Consequently, any payment resulting from a negative state aid decision should be seen as additional income tax.74 Additionally, while the regulatory definition of “income tax” specifically excludes penalties, fines, interests, customs duties, and similar payments,75 there is no indication that any payment to a member state would constitute a fine or penalty. A company that engaged the EU member state and followed the specific directives of that state in calculating its income tax liability could hardly be accused of not following the law of that state.

Another relevant question is whether a taxpayer will be seen as pursuing all “effective and practical” remedies to reduce the amount of taxes payable. The Treasury Regulations contemplate balancing the cost of pursuing the remedy (including additional or offsetting tax liability) against the amount at issue and the likelihood of success.76 A taxpayer need not exhaust all litigation remedies with respect to firmly establishing its liability (or lack thereof) for the levy before applying for the credit.77 The degree to which a taxpayer must pursue available remedies remains unclear even in typical disputes with foreign taxing authorities. In the state aid cases, where the amount to be paid is driven by a EC decision against the EU member state rather than against the U.S. taxpayer, there appears to be no precedent regarding what steps, if any, the U.S. taxpayer should take. However, a taxpayer’s advocacy in the state aid investigation process coupled with a taxpayer’s subsequent advocacy in the determination of any final tax adjustment with the EU member state would presumably satisfy this element.

Conclusion

Prior to its recent focus on tax rulings, the EC has used the state aid concept to address certain isolated tax issues. Thus, one cannot say that the EC’s recent use of state aid control to challenge EU member states’ application of tax rules is totally unprecedented. But, the EU-wide scope, the forcefulness of the EC actions and the manner in which the EC has challenged EU member state applications of international tax principles, is unprecedented. The EC’s vigorous, high-profile pursuit of tax rulings and tax ruling regimes has drawn the attention and criticism of not only the subject member states, but also widespread segments of the business and academic communities. Moreover, in an era of large differences in the views of the political parties in the United States over other tax issues, the EC’s actions have succeeded in uniting a bipartisan consensus of U.S. government officials and politicians in sharply criticizing the EC’s actions.

While the EC’s opening of formal investigations is outside of any company’s direct control, multinational corporations should review their rulings, APAs, and informal and formal agreements with EU member states to determine if there is any risk of such an investigation. If an investigation relating to a ruling or other agreement does arise, companies should monitor the investigation and advocate for their position in the EC and, if need be, the EU member state. Such an advocacy role should be undertaken, to the extent possible, at every step in the process in order to support eventual FTC eligibility for any subsequent payments.

Nicholas J. DeNovio is a partner in the Washington, D.C., office of Latham & Watkins and global chair of the firm’s international tax practice. Elisabetta Righini is counsel in the antitrust and competition practice in the Brussels, Belgium, office of Latham & Watkins and visiting professor at the Centre of European Law of the King’s College London School of Law. She was formerly legal and policy adviser to the former competition commissioner and vice president of the European Commission. Nicolle Nonken Gibbs is an associate in the tax department of the Washington, D.C., office of Latham & Watkins.

Endnotes

- The FSC regime, found in former Internal Revenue Code (Code) §§ 921-927, allowed a U.S. company to sell products or services to a subsidiary, the FSC. The FSC would in turn sell the goods or services to a foreign buyer. The FSC regime allocated income to the FSC based on the services it performed for the U.S. company, such as negotiating contracts and scheduling and fulfilling deliveries. Qualifying income earned by the FSC was given favorable tax treatment in the U.S. In 1999, the WTO concluded that the FSC regime constituted a “subsidy contingent on exporting.” World Trade Organization, “United States—Tax Treatment for Foreign Sales Corporations,” Report of the Appellate Body, Feb. 24, 2000, AB-1999-9. After several years of transatlantic legal wrangling, the FSC regime was repealed in favor of the short-lived ETI regime and finally replaced by Code § 199.

- The conflict with the United States relating to the FSC regime was also forward-looking, while recovery for violation of state aid law can go back up to ten years. The implications of state aid control are therefore more far-reaching for taxpayers than the implications of the WTO decisions.

- The only similar precedent relates to fifteen state aid investigations the EC launched in 2001 into the coordination centers of twelve EU member states. (See Europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-01-982_en.pdf).

- See, e.g., J. P. Finet, “Vestager Willing To Investigate Google’s U.K. Tax Deal,” Worldwide Tax Daily, Doc 2016-1942 (Jan. 29, 2016) (Noting that Commissioner Margrethe Vestager has indicated that “[t]he European Commission will investigate the recent tax agreement the U.K. reached with Google if asked”).

- See discussion on page 22 regarding U.S. foreign tax credit issues.

- Art. 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) (2007) (“Save as otherwise provided in the Treaties, any aid granted by a Member State or through State resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods, shall in so far as it affects trade between Member States, be incompatible with the internal market.”). The EC is the sole authority tasked with assessing whether any action by an EU member constitutes state aid and whether it can nonetheless be acceptable because in line with common European objectives (for instance in terms of regional developments, environment protection, and many others). Any decision of the EC is subject to judicial review in front of the European Courts in Luxembourg (the EU General Court and the Court of Justice of the European Union).

- Since its very creation, the European project has foreseen a generalized prohibition on state aid, together with antitrust control, as the second pillar of the internal market next to regulatory intervention. However, if other objectives beyond free market and free competition have to be protected, these can justify an exception to the absolute prohibition of State intervention in the economy. Thus, in such situations, the state aid may be declared compatible, in line with Article 107(2) and (3) TFEU.

- See, for example, Commission Decision C(2015) 5642 of Aug. 12, 2015, in which the EC accepted as compatible state aid a Czech Republic’s law providing incentives for private investment in the construction of sufficient trans-shipping capacity, available at ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/255511/255511_1685635_116_2.pdf. A more recent and more telling example of state aid enforcement concerns the banking sector where, between Oct, 1, 2008, and Oct. 1, 2014, the commission issued more than 450 decisions authorizing state aid measures to support the financial sector during the Great Recession. Of the approved aid, €892.6 billion (29.8 percent of EU GDP in 2013) was approved for guarantees on liabilities; €821.1 billion (6.3 percent of EU 2013 GDP) was approved for recapitalizations; €379.9 billion (2.9 percent of EU 2013 GDP) was approved for short-term liquidity measures, and €188.2 billion (1.4 percent of EU 2013 GDP) was approved for asset relief measures. See EC State Aid Scoreboard 2014, “Aid in the context of the financial and economic crisis”, available at ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/scoreboard/financial_economic_crisis_aid_en.html.

- An example concerns the Spanish financial goodwill amortization cases. In 2002, Spain adopted legislation allowing Spanish companies to deduct from their taxable base the difference between (i) the acquisition cost of a five percent or higher stake in a foreign company and (ii) the net book value of the company up to a certain amount. In 2009 and 2011, the EC found that this measure constituted unlawful state aid because it resulted in an advantage for Spanish companies over their competitors when acquiring shares in foreign companies. In 2014, the EC found that unlawful state aid exists also when the acquisition is indirect (i.e., the Spanish entity acquires shares of a holding company which then buys the shares in the foreign company). In 2014, the EU General Court, a constituent court of the Court of Justice of the European Union, annulled both the 2009 and 2011 EC decisions.

- Commission Notice 98/C 384/03 (Oct 12, 1998).

- As early as the 1970s, the EC used state aid to strike down an entire tax regime. See, e.g., Case 173/73 Italy v. Commission [1974] ECR 709. In 1998 the EC issued a notice on the application of the state aid rules “to measures relating to direct business taxation.” Commission Notice 98/C 384/03. This notice set forth four factors to be considered in determining whether certain tax measures would constitute state aid, which continue to be used today.

- Commission Recommendation of 6.12.2012 on aggressive tax planning, COM(2012) 8806, final.

- Commission Recommendation of 6.12.2012 regarding measures intended to encourage third countries to apply minimum standards of good governance in tax matters, COM(2012) 8805, final.

- Id.

- European Commission—Press Release, “Statement of Margrethe Vestager” (Dec. 3, 2015), available at europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-6221_en.htm.

- Almunia, Joaquín, “Fighting for the Single Market,” European Competition Forum, Brussels, Belgium, Feb. 11, 2014, available at europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-14-119_en.htm.

- European Commission—Press Release, “State Aid: Commission Orders Luxembourg To Deliver Information on Tax Practices” (Mar. 24, 2015), available at europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-309_en.htm.

- European Commission, “Consultation on the Notice on the Notion of State Aid and Communication From the Commission — Draft Commission Notice on the Notion of State Aid Pursuant to Article 107(1) TFEU” ¶ 177, available at ec.europa.eu/competition/consultations/2014_state_aid_notion/draft_guidance_en.pdf.

- European Commission—Press Release, “State Aid: Commission Extends Information Enquiry on Tax Rulings Practice to All Member States” (Dec. 17, 2014), available at europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-2742_en.htm.

- European Commission—Press Release, “Commission Decides Selective Tax Advantages for Fiat in Luxembourg and Starbucks in the Netherlands Are Illegal Under EU State Aid Rules” (Oct. 21, 2015), available at europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-5880_en.htm.

- European Commission—Press Release, “State Aid: Commission Opens Formal Investigation Into Luxembourg’s Tax Treatment of McDonald’s” (Dec. 3, 2015), available at europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-6221_en.htm.

- Commission Decision SA.37667, Belgium—Excess Profit exemption, C(2015) 563, final.

- European Commission—Press Release, “State Aid: Commission Opens In-Depth Investigation Into The Belgian Excess Profit Ruling System” (Feb. 3, 2015), available at europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-4080_en.htm/.

- See Fairless, Tom, “EU Orders Belgium to Recover Unpaid Taxes From 35 Firms,” The Wall Street Journal (Jan. 11, 2016), available at www.wsj.com/articles/eu-to-rule-on-illegal-tax-breaks-for-multinationals-1452506740.

- All state aid granted in Europe should be notified by the member states to the European Commission and approved before being put into effect. Article 108(3) TFEU and Article 2 of Regulation No. 659/1999. This obligation covers any new tax provisions, such as a new tax credit, that can be qualified as state aid. When state aid is not notified, such as with the tax ruling regimes, the European Commission can begin a formal investigation also on the basis of a complaint or of its own motion.

- European Commission—Press Release, “State Aid: Commission Investigates Transfer Pricing Arrangements on Corporate Taxation of Apple (Ireland) Starbucks (Netherlands) and Fiat Finance and Trade (Luxembourg)” (June 11, 2014), available at europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-14-663_en.htm. (“Tax rulings as such are not problematic: they are comfort letters by tax authorities giving a specific company clarity on how its corporate tax will be calculated or on the use of special tax provisions. However, tax rulings may involve State Aid within the meaning of EU rules if they are used to provide selective advantages to a specific company or group of companies.”).

- According to the EU Courts, “… so far as State aid is concerned, it is settled case-law that, in view of the mandatory nature of the review of State aid by the Commission …, undertakings to which aid has been granted may not, in principle, entertain a legitimate expectation that the aid is lawful unless it has been granted in compliance with the procedure. A diligent business operator must normally be in a position to confirm that that procedure has been followed …”, Judgment of June 15, 2010, Mediaset/Commission (T-177/07, Rec._p._II-2341) (cf. point 173).

- Article 4(4) of Council Regulation No. 2015/1589 (Jul. 13, 2015), replacing Council Regulation No 659/1999 (Mar. 22, 1999) (“Where the Commission, after a preliminary examination, finds that doubts are raised as to the compatibility with the internal market of a notified measure, it shall decide to initiate proceedings pursuant to Article 108(2) TFEU (‘decision to initiate the formal investigation procedure’)”). See, e.g., EC Decision C(2014) 3626, final (June 11, 2014); EC Decision C(2014) 3606, final (June 11, 2014).

- Article 108(2) TFEU; Articles 6(1), 20(1) of Regulation No. 2015/1589 (Jul. 13, 2015), replacing Council Regulation (EC) No. 659/99 (Mar. 22, 1999) (“The decision to initiate the formal investigation procedure shall summarise the relevant issues of fact and law, shall include a preliminary assessment of the Commission as to the aid character of the proposed measure and shall set out the doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market. The decision shall call upon the Member State concerned and upon other interested parties to submit comments within a prescribed period which shall normally not exceed one month. In duly justified cases, the Commission may extend the prescribed period.”).

- Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (1957).

- Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (2007).

- The EC explained how these factors were specifically applied to tax measures in Commission Notice 98/C 384/03.

- To be considered an “advantage” to recipients, the tax measure must relieve such recipients “of charges that are normally borne from their budgets.” Commission Notice 98/C 384/03. To determine whether a tax measure (or entire tax regime) confers an advantage to a specific beneficiary, the EC may compare the tax measure or regime with the common, generally applicable tax system, frequently termed a “reference system.” Id.

- As stated above, the EC takes the position that “a loss of tax revenue is equivalent to consumption of State resources in the form of fiscal expenditure.” Commission Notice 98/C 384/03. As a result, this factor will always be met in a tax case.

- The EC views this factor as being met so long as the beneficiary engages in economic activity that involves trade between EU member states. Commission Notice 98/C 384/03.

- To determine if the tax measure is selective with respect to a particular measure, the EC will examine whether the measure results in different treatment of companies in a similar legal and factual situation. If the measure results in different treatment, it may still not be considered selective the different treatment arises from the nature or logic of the reference tax system. Commission Notice 98/C 384/03.

- See article 25 of Council Regulation (EU) 2015/1589 of July 13, 2015, laying down detailed rules for the application of Article 108 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, OJ L 248, 24.9.2015, p. 9. For a comprehensive commentary of the recovery obligation see E. Righini, “Godot Is Here: Recovery as an Effective State Aid Remedy,” in EC State Aid Law—Liber Amicorum Francisco Santaolalla Gadea (Kluwer Law International, 2008).

- Id.

- Case C-331/09, European Commission v. Republic of Poland, ECLI:EU:C:2011:250, at point 33.

- The EU General Court has jurisdiction to hear and determine actions brought by individuals and companies in the first instance.

- Article 263 TFEU.

- See Case C-583/11 P, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and Others v. Parliament and Council (Judgment of Oct. 3, 2013) ¶ 93.

- See supra note 9.

- EC Decision C(2014) 3626, final (June 11, 2014); EC Decision C(2014) 3606, final (June 11, 2014). The EC issued a final decision determining that the aid at issue in the Netherlands ruling constitutes impermissible state aid on Oct. 21, 2015 (EC Decision C(2014) 3626). The EC is still investigating the Ireland ruling.

- EC Decision C(2014) 3606, final (June 11, 2014).

- Id. See also OECD, OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations, 2010.

- The EC was of the view that a ruling used for such a lengthy time period without reassessment is contrary to the arm’s-length principle set forth by the OECD.

- EC Decision C(2014) 3606, final (June 11, 2014).

- EC Decision C(2014) 3626, final (June 11, 2014).

- Id. at ¶¶ 118-122.

- Id. at ¶ 90. This point is particularly concerning because the EC is questioning the specific business decisions and roles of companies within an intercompany structure itself rather than just questioning whether amounts paid between the companies were at arm’s length.

- European Commission—Press Release, “Commission Decides Selective Tax Advantages for Fiat in Luxembourg and Starbucks in the Netherlands Are Illegal Under EU State Aid Rules,” (Oct. 21, 2015), available at europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-5880_en.htm. The Netherlands has formally appealed the decision. See Case T-760/15, Netherlands v. Commission (Action brought on Dec. 23, 2015).

- See Case T-760/15, Netherlands v. Commission (Action brought on Dec. 23, 2015); Case T-755/15, Luxembourg v. Commission (Action brought on Dec. 30, 2015).

- European Commission—Press Release, “Commission/Luxembourg To Appeal the Commission’s Fiat Decision,” (Dec. 4, 2015), available at www.mf.public.lu/actualites/2015/12/fiat_041215/index.html.

- “Cabinet Response to the European Commission Decision on Starbucks Manufacturing BV” (Nov. 27, 2015), available at www.government.nl/binaries/government/documents/parliamentary-documents/2015/11/30/cabinet-response-to-the-european-commission-decision-on-starbucks-manufacturing-bv/cabinet-response-to-the-european-commission-decision-on-starbucks-manufacturing-bv.pdf.

- Id.

- Alan Hope, “Belgium will appeal EU decision on excess profits” Flanders Today, available at www.flanderstoday.eu/politics/belgium-will-appeal-eu-decision-excess-profits.

- Letter from Myron A. Brilliant, executive vice president and head of international affairs, Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America, to Margrethe Vestager, commissioner for competition, European Commission (Dec. 5, 2014).

- Id.

- “U.S. Chamber Statement on EU State Aid Decisions” (Oct. 21, 2015), available at www.uschamber.com/press-release/us-chamber-statement-eu-state-aid-decisions.

- Michael J. Graetz, “Behind the European Raid on McDonald’s,” The Wall Street Journal (Dec. 3, 2015), available at www.wsj.com/articles/behind-the-european-raid-on-mcdonalds-1449187952.

- Id. Note that Dan Shaviro, Wayne Perry Professor of Taxation at New York University School of Law, proposes that the United States may not directly bear a burden, because the subject earnings in these cases might have been subject to indefinite deferral or in any case limited U.S. residual tax. Shaviro speculates that any such payment to the EU member state would prompt a U.S. multinational to repatriate earnings to the United States. But he also asks whether, absent the EC actions, such a repatriation would have ever taken place, thus calling into question whether the U.S. fisc is indeed paying for the EC actions. In other words, Shaviro argues that a U.S. residual tax on those earnings may never have been triggered, due to indefinite deferral or an eventual tax holiday from Congress or permanent tax reform. Dan Shaviro, “Foreign Tax Credits to the Rescue?”, (Dec. 5, 2015), available at danshaviro.blogspot.com/2015/12/foreign-tax-credits-to-rescue.html.

- Stephanie Soong Johnston, “Stack Questions Fairness of EU State Aid Investigations” Worldwide Tax Daily, Doc 2015-27774 (Dec. 18, 2015).

- Testimony of Robert Stack Before the Senate Finance Committee, Dec. 18, 2015, available at www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/01dec2015Stack.pdf.

- Stephanie Soong Johnston, “Stack Questions Fairness of EU State Aid Investigations” Worldwide Tax Daily, Doc 2015-27774 (Dec. 18, 2015).

- Testimony of Robert Stack Before the Senate Finance Committee, Dec. 1, 2015, available at www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/01dec2015Stack.pdf. At least one commentator has also argued that U.S. based multinationals are the recipient of more such rulings. See, e.g., Itai Grinberg, “A Constructive U.S. Counter to EU State Aid Cases,” 81 Tax Notes International 167 (Jan. 11, 2016).

- Id. See also Stephanie Bodoni “Treasury’s Stack Criticizes EU Probes of American Companies” 20 Daily Tax Report, I-1 (Jan. 29, 2016).

- Teri Sprackland, “Stack Meets With EU Officials Over Crackdown on Multinationals,” 150 Tax Notes 605 (Feb. 8, 2016).

- Senate Finance Committee letter to Treasury Secretary Jack Lew on U.S. concerns about European Commission state aid investigations (Jan. 15, 2016), available at www.finance.senate.gov/chairmans-news/finance-committee-members-push-for-fairness-in-eu-state-aid-investigations-.

- Id.

- Id. (internal quotations omitted). See also, Itai Grinberg, “A Constructive U.S. Counter to EU State Aid Cases,” 81 Tax Notes International, 167 (Jan. 11, 2016).

- Readers of this journal are knowledgeable on the workings of the FTC, and there is no need for a detailed discussion of many of the requirements to obtain a FTC.

- Treas. Reg. § 1.901-2(a).

- It is not clear how an EU member state would impose this burden, but presumably it would do so under its normal procedures to assess taxes for prior years (i.e., the equivalent of an IRS Notice of Proposed Adjustment).

- Treas. Reg. § 1.901-2(a).

- Treas. Reg. § 1.901-2(e)(5)(i).

- International Business Machines Corp. v. United States, 38 Fed. Cl. 661, 668-69 (1997) (citing § 1.901-2(e)(5)(i)).