Due to the disruptions and economic shutdowns caused by COVID-19, many corporate taxpayers will have net operating losses (NOLs) in 2020. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act offers these taxpayers the opportunity to turn 2020 NOLs into cash refunds. The CARES Act revived the NOL carryback that was previously eliminated by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA). For a limited time, 2018, 2019, and 2020 NOLs can be carried back for up to five years.

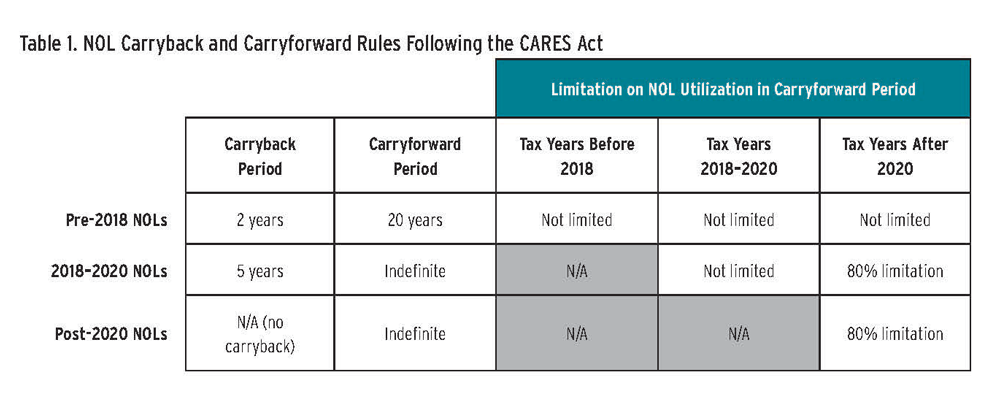

Prior to this CARES Act amendment, the TCJA had eliminated carrybacks and permitted NOLs to be carried forward indefinitely for post-2017 NOLs subject to a limitation of eighty percent of taxable income (hereafter called the eighty percent limitation). Special rules apply to non-life insurance companies (that is, insurance companies other than life insurance companies) and farming losses. Non-life insurance companies are allowed to carry NOLs back two years and forward twenty years and are not subject to the eighty percent limitation. Farming losses may be carried back two years and carried forward indefinitely, subject to the eighty percent limitation.

Under the TCJA as modified by the CARES Act, an NOL deduction for the year is the sum of 1) the total NOLs arising in taxable years beginning before January 1, 2018 (pre-2018 NOLs) that are carried to that year plus 2) the lesser of the total of NOLs arising in taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017 (post-2017 NOLs), or eighty percent of taxable income less pre-2018 NOLs.

Corporate taxpayers with taxable income during the 2015‒2019 tax years should consider the potential benefit of maximizing 2020 NOLs to claim a refund from those earlier tax years. It is important to accelerate or otherwise maximize losses in 2020, because unless Congress extends the CARES Act NOL carryback provision, losses recognized beyond 2020 may only be carried forward (and NOL carryforwards from taxable years beginning after 2017 are subject to an eighty percent limitation when carried to tax years beginning after December 31, 2020).

In some circumstances, however, it may not be in a taxpayer’s best interest to maximize its 2020 losses or to carry them back. For example, as discussed below, the interaction of NOL carrybacks with other TCJA provisions (for example, GILTI, BEAT, and Section 965) may make such carrybacks inadvisable. In addition, if tax rates are expected to rise in future years, an NOL may be more valuable in a subsequent tax year than during the post-TCJA reduced-rate years. In addition, the rules under Section 382 regarding ownership changes and the resulting limitations on NOLs and other tax attributes must be considered in connection with NOL planning. Taxpayers must also consider state and local tax implications, since state and local income tax calculations based on federal taxable income may be affected. Many states do not conform to the CARES Act provisions and, even where they do, some states limit the ability of certain taxpayers to carry back NOLs.

Potentially Surprising TCJA Interactions

Taxpayers considering carrying back NOLs to 2017 and later taxable years will need to consider a variety of potential interactions with the TCJA. As described in more detail below, NOL carrybacks to 2017 and later years may be considerably less valuable than NOL carrybacks to earlier years. Moreover, although taxpayers can waive the carryback of NOLs to Section 965 inclusion years, they cannot elect what years NOLs may be carried back to on a year-by-year basis.1

Taxpayers carrying back NOLs to 2017 and 2018 will need to consider the potential interaction of the NOL carryback with their Section 965 inclusion. Section 965 imposes a transition tax on earnings of controlled foreign corporations (CFCs) in connection with tax reform. Whether 2017 or 2018 or both were Section 965 inclusion years for a taxpayer depends on the year-end of the CFCs to which the Section 965 transition tax applied. Because these CFC earnings were taxed at a lower rate than corporate income in general, Congress permitted taxpayers to elect under Section 965(n) not to apply NOLs to offset their Section 965 inclusion so taxpayers could instead utilize NOLs to offset income taxed at a higher rate. In addition, Section 965(h) permitted taxpayers to elect to pay their Section 965 transition tax liability over an eight-year period. The CARES Act prevents taxpayers from utilizing NOL carrybacks to offset their Section 965 inclusion by deeming the Section 965(n) election to be made with respect to such NOLs.2 However, it does not prevent the Internal Revenue Service from using refunds taxpayers would otherwise be eligible to claim for Section 965 inclusion years to offset unpaid future installment payments due from having made a Section 965(h) election. As a result, taxpayers with significant unpaid Section 965 installments may want to waive the carryback of NOLs to Section 965 inclusion years.

Taxpayers carrying back NOLs to 2018 and 2019 also need to consider the potential interaction of NOL carrybacks with Section 250. For 2018 and 2019, Section 250 provides a fifty percent deduction with respect to global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) earned in those years.3 As a result, corporations subject to GILTI generally are taxed at 10.5 percent after taking into account the Section 250 deduction prior to accounting for foreign tax credits. Similarly for 2018 and 2019, Section 250 provides a 37.5 percent deduction with respect to foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) earned in those years.4 As a result, FDII is generally taxed at 13.125 percent. However, the Section 250 deduction is limited to taxable income.5 Consequently, if a corporation carries back NOLs to 2018 and 2019, it may lose some or all of its Section 250 deduction and be subject to tax on its GILTI and FDII income at a full 21 percent for those years.

In addition, taxpayers carrying back NOLs to 2018 and 2019 should consider the potential interaction of NOL carrybacks with the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT). In general, the BEAT is calculated by comparing the calculation of regular taxable income to modified taxable income calculated without base erosion payments and certain tax credits, including foreign tax credits.6 Although carrying back NOLs will reduce regular taxable income for a given year, it will not change the way in which modified taxable income is calculated. As a result, a taxpayer subject to the BEAT in 2018 or 2019 may have increased BEAT liability for those years after carrying back NOLs. Furthermore, a taxpayer that was not previously subject to the BEAT in 2018 or 2019 may have BEAT liability after taking NOL carrybacks to those years into account.

Claiming CARES Act NOL Carrybacks

To carry back an NOL from a taxable year, the corporation must first file a tax return for the loss year showing an NOL. Calendar-year taxpayers cannot claim a 2020 carryback without filing a Form 1120 for the 2020 calendar year. Unfortunately this means that calendar-year taxpayers cannot use the expedited fax hotline to file refund claims on Form 1139 (discussed below) unless the IRS extends the deadline for using the hotline, which was set to expire on December 31, 2020.

To try to accelerate the refund claim, a taxpayer could file an initial Form 1120 for 2020 based on estimates showing an NOL, thereby allowing the taxpayer to make a refund claim. The taxpayer could subsequently file a superseding Form 1120 before the due date (including extension if applicable) with the final amounts. This could allow a taxpayer to get a refund claim on file faster than waiting until the Form 1120 is final.

Corporate taxpayers generally have two options for making a refund claim, with several differences between the two options that should be weighed carefully. The taxpayer can make a carryback claim on Form 1139 (Corporation Application for Tentative Refund) or on Form 1120X (Amended US Corporate Income Tax Return) for each of the carryback years.

The quickest way to obtain a refund is by filing Form 1139, known as a “quickie refund” claim. In theory, the IRS is required to process these applications and issue a refund within ninety days of the later of 1) its receipt of a completed application or 2) the last day of the month that includes the due date (including extensions) for filing the corporation’s income tax return for the year in which the NOL arose.

The IRS set up a special fax number to process Form 1139 filings and indicated that faxed refund claims will be processed in the order received. However, the fax number expired at midnight Eastern Time on December 31, 2020. After that date, taxpayers will need to file Form 1139 by regular mail. Because of the substantial backlog and reduced resources, it is likely that refund claims submitted on Form 1139 by mail could take significantly longer than ninety days to process.

Generally, the corporation must file Form 1139 within twelve months of the end of the tax year in which an NOL arose. However, if a corporation had an NOL that arose in a tax year that began during calendar year 2018 and ended on or before June 30, 2019, the corporation is allowed a six-month extension to file Form 1139. If a corporation’s tax year ends because it has joined a group of consolidated corporations, the twelve-month (or eighteen-month as applicable) deadline to file begins at the end of the full tax year of the acquiring group of consolidated corporations—not from the end of the short year triggered by joining the group.

The benefit of using Form 1139 is the speed of obtaining a refund. The taxpayer can obtain a refund prior to an IRS examination of the return year that is generating the NOL and before a Joint Committee on Taxation review that is required when the refund exceeds $5 million. The primary drawback of using Form 1139 is that it allows only for a “tentative” refund, and the payment of the claim does not mean the IRS has accepted it as accurate. If the IRS later determines the claimed refund amount is overstated and negligent, penalties may be assessed. Furthermore, if Form 1139 is rejected due to a mistake that cannot be cured within twelve months of the close of the tax year of the loss, then the taxpayer must file an amended tax return on Form 1120X to claim the credit.

The second way to claim a refund from an NOL carryback is to file an amended tax return on Form 1120X for each of the years to which the carryback applies. The deadline for filing this claim is three years after the filing date of the return for the tax year in which the NOL arose (or the original due date of that return if it was filed early).

The benefit of this procedure is that it does not provide a tentative refund, but the detriment is that processing time can be longer than that for filing Form 1139. The additional time arises from the fact that the ninety-day expedited review process for Form 1139 does not apply, the Form 1120X must be filed by mail (because the fax procedure described above no longer applies), and refunds claimed on Form 1120X will be subject to Joint Committee on Taxation review if the refund exceeds $5 million.

In addition to the claim for the refund attributable to the carryback of an NOL, some other items must be considered in the refund filing. If the taxpayer would prefer to waive the NOL carryback to the Section 965 inclusion years (as discussed above), then it can do so by following the procedures set forth in Revenue Procedure 2020-24. A taxpayer must make an election to exclude Section 965 inclusion years from the carryback period for an NOL arising in a taxable year beginning in 2018 or 2019 by the due date (including extensions) for filing its return for the first taxable year ending after March 27, 2020. For an NOL arising in a taxable year beginning in 2020, the election must be made by the due date (including extensions) for filing the federal income tax return for that taxable year. Additionally, if the carryback of an NOL to a pre-2018 tax year would result in an alternative minimum tax for that year, the taxpayer can use the resulting minimum tax credits or request a refund of those minimum tax credits on the applicable Form 1139 or 1120X.

A refund claim is filed by the corporation incurring and carrying back the NOL. The claim must be signed by an authorized officer of the corporation at the time of filing. If a corporation was sold after the carryback period but before the loss period, the transaction documents governing the sale might affect the corporation’s ability to file a carryback refund claim or to address which party is entitled to any refund received. Those documents should be carefully reviewed.

The purchase agreement might force the corporation to waive the carryback or provide that if an NOL is carried back, any refund is for the benefit of the seller. In such case, the buyer would generally carry forward the NOL for use in future years. However, if the carryback period is to a pre-2018 tax year, such that a refund of taxes imposed at a thirty-five percent rate is available, there is a fourteen percent arbitrage that could allow the buyer and the seller to agree on a split of the refund proceeds.

If the purchase agreement provides that the buyer is entitled to any refunds from a carryback, or if it does not address refunds, then the buyer might be able to obtain 100 percent of the benefit of any refund claim. The relevant parties should carefully analyze any contractual provisions in the purchase agreement applicable to claiming and obtaining tax refunds in addition to the procedural considerations described above.

Split-Waiver Election of NOL Carrybacks

A consolidated group generally must make a single election to waive the carryback of an NOL on a groupwide basis. However, existing consolidated return regulations permit a consolidated group to separately elect to waive the carryback of NOLs allocable to an acquired member to the extent that such a carryback would be to a different consolidated group without waiving the carryback of the remainder of the group’s NOLs. This split-waiver election, under Treasury Regulation 1.1502–21(b)(3)(ii)(B), must be attached to the acquiring consolidated group’s original tax return for the year of the acquisition of the member (that is, not the year in which the NOL is incurred). This is not a yearly election and cannot be made on an amended tax return. Instead, it applies to all consolidated NOLs (CNOLs) attributable to an acquired member that otherwise would be subject to a carryback to a taxable year of a former group to which the acquired member belonged.

Given that many groups may not have made these elections on originally filed tax returns with respect to corporations acquired after the enactment of the TCJA provisions repealing NOL carrybacks for corporations, the IRS issued temporary regulations that add new provisions allowing acquiring consolidated groups to make an irrevocable split-waiver election in a year after the year of acquisition.

Additional Split-Waiver Elections Under Temporary Regulations

The temporary regulations add two more types of split-waiver elections covering circumstances where Congress amends the NOL carryback period applicable to a group’s NOLs. These elections must be made with the tax return for the year the NOL is incurred for which Congress amended the carryback rules. In the event that such a return is due prior to the date that is 150 days after the date of the statutory amendment to the carryback rules, an amended return may be filed to make these elections, provided that this amended return is filed within that 150-day period.

The temporary regulations apply to any CNOLs arising in a taxable year ending after July 2, 2020. However, taxpayers may apply the provisions to any CNOLs arising in a taxable year beginning after December 31, 2017. The temporary regulations will expire on July 3, 2023.

The two additional types of temporary split-waiver elections are as follows.

Amended Statute Split-Waiver Election

The amended statute split-waiver election permits an acquiring group to relinquish that part of the carryback period of the acquired member’s NOL during which it was a member of a former group. The election applies only to the portion of a CNOL that is attributable to the acquired member for the portion of the carryback period during which the acquired member was a member of a former group. The acquiring group makes an amended statute split-waiver election on a year-by-year basis with respect to the acquired member’s NOL for that year.

Extended Split-Waiver Election

Alternately, acquiring groups can make an extended split-waiver election that applies solely to the extended carryback period (that is, the additional carryback years provided under the amended carryback rules). The election affects only the extended carryback period for an acquired member’s attributed loss.

Applying the 80% Limitation Under New Consolidated Return Regulations

In October 2020, the IRS published new final regulations that explain how the eighty percent limitation on post-2017 NOLs applies to consolidated groups. As a result of the CARES Act amendments, the eighty percent limitation does not apply to tax years beginning before January 1, 2021. The regulations generally implement the eighty percent limitation on a consolidated group basis by limiting a group’s deduction of post-2017 NOLs for any such taxable year to the lesser of:

- the aggregate amount of post-2017 NOLs carried to that taxable year;

- or eighty percent of the excess (if any) of the group’s consolidated taxable income (CTI)—computed without regard to any deductions under Sections 172, 199A, and 250—over the aggregate amount of pre-2018 NOLs carried to that year.

As a result, the amount allowed as a deduction for a particular consolidated return beginning after December 31, 2020, equals the sum of:

- pre-2018 NOLs carried to that year; and

- post-2017 NOLs carried to that year after applying the eighty percent limitation described above.

The regulations also provide special rules applicable to consolidated groups that include at least one non-life insurance company as well as rules applicable to losses arising in a separate return limitation year (SRLY). Groups whose members include both non-life insurance company members, such as a captive insurance company, and other types of companies must follow a multistep process to determine the group’s CNOL deduction for the year:

Step 1. Create two pools of income/loss, one pool for non-life insurance company members and a second pool for other members of the group;

Step 2. Allocate pre-2018 NOL carryovers between these two income pools based on the relative amounts in each pool;

Step 3. The limitation on post-2017 NOLs available to offset the remaining pool of income from the non-life insurance company members (after reduction for the pre-2018 NOLs) is equal to the total post-2017 NOL carryovers to that year; and

Step 4. The limitation on post-2017 NOLs available to offset the remaining pool of income from the other members of the group (after reduction for the pre-2018 NOLs) is equal to eighty percent of that amount.

If one of the two pools (non-life insurance or other) is less than zero (that is, a loss), however, the regulations provide that one must net the two first and apply the eighty percent limitation to post-2017 NOL carryovers only if the non-life insurance income pool was less than zero.

For losses from SRLYs, the regulations provide that the SRLY limitation must be determined so as to reflect the eighty percent limitation on post-2017 NOLs. For taxable years beginning after December 31, 2020, this provision effectively requires a SRLY limitation of $100 to permit the deduction of $80 of post-2017 NOLs.

For calendar-year taxpayers, the regulations are applicable to losses arising in taxable years beginning January 1, 2021. However, a taxpayer deducting post-2017 NOLs may rely on the regulations concerning the treatment of post-2017 NOLs if the taxpayer relies on the regulations consistently and in their entirety.

Bryan P. Collins is a managing director at Andersen. David Peck is a partner at Vinson & Elkins LLP. Jay Singer is a partner at Shearman & Sterling LLP.

Endnotes

- Internal Revenue Code (hereafter IRC) Section 172(b)(1)(D)(v).

- IRC Section 172(b)(1)(D)(iv).

- IRC Section 250(a)(1)(B).

- IRC Section 250(a)(1)(A).

- IRC Section 250(a)(2).

- IRC Section 59A.