Causes worthy of support are plentiful, and new ones seem to appear daily. How a company responds to societal needs is more important than ever. More than 2,800 corporate foundations are estimated to exist in the United States.1 Many companies are moving away from traditional or responsive models of philanthropy toward more strategic approaches using creative partnerships to solve society’s challenges. Most companies choose to participate in philanthropy in one or more of three important ways:

- making grants to existing charitable organizations in communities where the company and its related entities and workforce have a significant presence;

- centering philanthropy on the company’s workforce, such as matching gift programs, workforce development and education, scholarships for children of company employees, or employee assistance (disaster/hardship relief) to address unexpected needs; and

- using elevated thinking and solutions to address societal issues as an investment.

Companies might use multiple methods to deploy resources efficiently and flexibly for charitable purposes, including:

- direct grants, a low-cost method for making charitable contributions;

- a donor-advised fund, which, for a fee, shifts the administrative burden to a third party;

- a charitable entity (a public charity or, more likely, a private foundation) to use company resources more efficiently for deferred and innovative giving; and

- a partnership with other organizations (charitable, government, and for-profit) to direct resources to particular needs.

Each option has its own costs, benefits, and degree of flexibility. The in-house tax professional often will be asked to participate in broader corporate discussions to determine which methods best meet the company’s charitable objectives.

The most complicated of these options is to establish a separate legal charitable entity, often a corporate foundation. Although some corporate foundations have their own employees and operate independently of the companies that established them, many share resources across several different company departments. Most often, the in-house tax department, from staff-level accountants up to the chief financial officer, is tasked with managing the foundation’s accounting and compliance and, in some instances, guiding program decisions based on tax law and regulatory schemes. Balancing compliance with these issues and empowering the foundation to meet charitable objectives, particularly when engaging in nontraditional philanthropy, can be challenging. But the in-house tax professional can play an important role in pulling together the appropriate corporate resources and thinking creatively about the company’s philanthropy. A well-rounded group of corporate professionals, coordinated by the in-house tax professional, could include representatives from the C-suite and the legal, treasury, and risk departments as well as participants from the program team, public relations, or other committees established to facilitate philanthropy.

Challenges of Regulatory Regimes

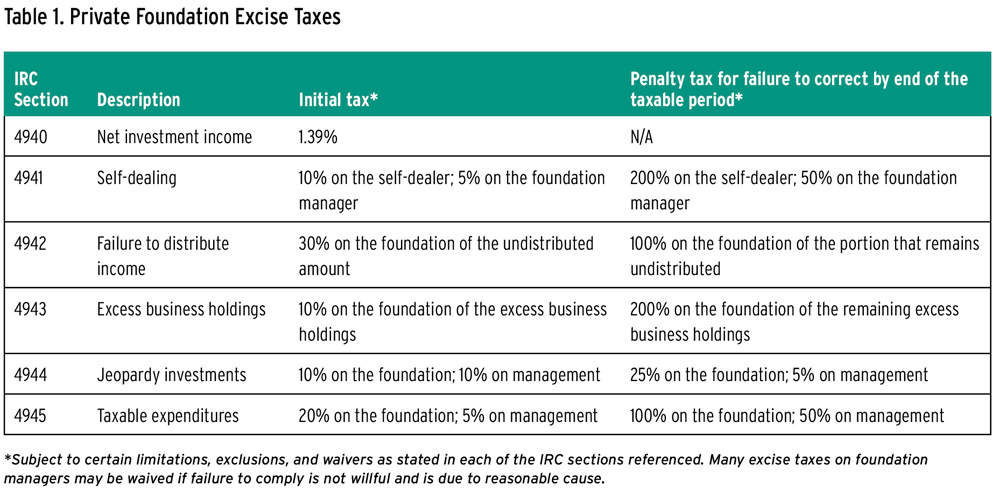

If a corporate foundation does not qualify as a publicly supported organization (such as, for example, a public charity), it will be described as a private foundation in Internal Revenue Code Section 509 and will be subject to the private foundation excise taxes described in IRC Sections 4940 through 4945. Although these excise taxes can pose challenges, implementing proper internal controls, approval requirements, and grant-making procedures usually can mitigate the gravest consequences.

Two of the excise taxes are grounded in mathematical computations: the excise tax on net investment income (Section 4940) and the excise tax on failure to distribute income (Section 4942). In-house tax professionals usually find themselves assisting the private foundation with these calculations, which could require preparing or reviewing the annual Form 990-PF (Return of Private Foundation) and, if required, Form 990-T (Exempt Organization Business Income Tax Return).

The other four excise taxes, delineated in Sections 4941, 4943, 4944, and 4945, should be viewed as prohibitions rather than as excise taxes, in that each requires the taxpayer to make a “correction” and imposes additional punitive taxes for failure to correct the activity that gives rise to the excise tax. In these cases, in-house tax professionals should work closely with colleagues in legal, treasury, public relations, grants administration, program, and program support to develop procedures that will allow the private foundation to pursue its charitable mission while mitigating regulatory issues.

Table 1 presents the broad strokes of each of the six IRC sections, including penalties for failure to comply.

Section 4940: Taxes Based on Income

Although a private foundation is exempt from federal income tax, it is subject to Section 4940, which imposes an excise tax of 1.39 percent on the private foundation’s net investment income. If the private foundation has income from any unrelated trade or businesses, it is also subject to the unrelated business income tax of Section 511 and must file Form 990-T. Many states also impose their own income taxes on unrelated business income and have a corresponding tax filing. In certain cases, a private foundation must make estimated tax payments on both its net investment income and unrelated business income.

Net investment income includes interest, dividends, rents, and royalties.2 It also includes capital gains3 that are subject to the 1.39 percent excise tax on net investment income. If the capital assets are received via a donation, the private foundation will retain the donor’s carryover basis and holding period for the appreciated stock and will have a taxable gain when the stock is sold. This situation routinely occurs when a corporation funds the corporate private foundation with stock contributions.

Section 4941: Self-dealing

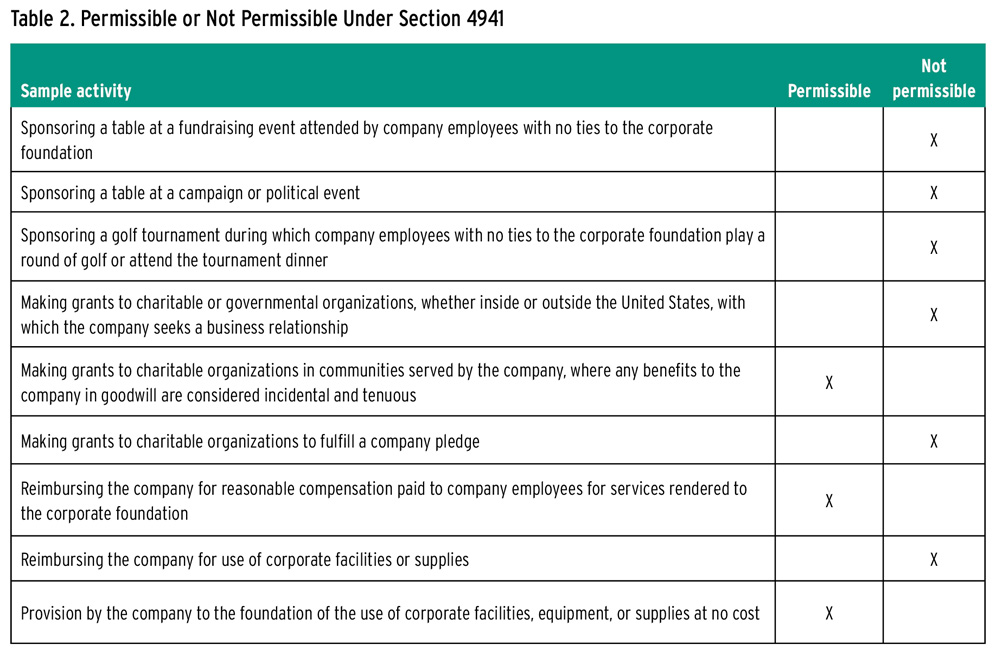

One of the more common challenges corporate foundations encounter results from transactions among the company, its private foundation, and the foundation’s other disqualified persons. Disqualified persons include (A) a substantial contributor to the foundation, (B) a foundation manager, (C) a more-than-twenty-percent owner of an entity that is a substantial contributor to the foundation, (D) a family member of any disqualified persons listed in (A), (B), or (C), and (E) any organization in which the previously listed disqualified persons own a share of more than thirty-five percent.4 Generally, Section 4941 prohibits most direct or indirect transactions between a company and its private foundation, even in cases where the transaction is fair and reasonable or benefits the corporate foundation, because that would be considered self-dealing. Corporate foundations cannot engage in activities intended to market the products or services of the company or that result in other tangible economic benefits to the company. The following types of transactions may be considered self-dealing:

- selling, exchanging, or leasing of property;

- lending money or otherwise extending credit;

- furnishing goods, services, or facilities;

- paying or reimbursing expenses;

- transferring to or using the private foundation’s income or assets; and

- paying money or other property to a

government official.5

Issues might arise in common situations where there are quid quo pro contributions, intangible benefits received by the company, employees providing services to both the company and the foundation, and assets shared between the company and the foundation. Table 2 presents common examples of potential self-dealing that could pose problems for a foundation at tax time.

Section 4942: Failure to Distribute Income

A private foundation must distribute, for charitable purposes, approximately five percent of its average monthly fair market value of noncharitable use assets annually.6 Since the exact amount of the calculation cannot be determined until the last day of the taxable year, the private foundation has until the last day of the following tax year to distribute the required amount.7 Failure to distribute the required amount triggers the excise tax under Section 4942.

Amounts distributed for charitable purposes are referred to as “qualifying distributions,” and for the foundation to meet the minimum requirement, these qualifying distributions include grants paid to government entities and public charities, expenses incurred in direct charitable activities, expenses allocable to charitable purposes,8 the purchase of assets placed in service for charitable purposes,9 and certain grants paid to other foreign or noncharitable entities when expenditure responsibility has been exercised.10 Any qualifying distributions beyond the required amount may be carried over for a five-year period.11

Sections 4943 and 4944: Excess Business Holdings and Jeopardy Investments

A private foundation may not hold, in total with its disqualified persons, more than twenty percent of the voting stock of a business enterprise.12 Even though this rule typically is irrelevant to publicly traded companies, it is a complicated issue for many closely held companies if their private foundation holds company stock. A private foundation may rely on a safe harbor de minimis rule that permits the private foundation to hold no more than two percent of the voting stock and no more than two percent of the value of all outstanding shares of stock.13 Additionally, a private foundation is not permitted to hold an investment that would jeopardize the carrying out of its exempt purpose.14 In the case of both prohibitions, exceptions exist for certain program-related investments.15 Program-related investments are investments whose primary purpose is to accomplish one or more of the charitable purposes described in IRC Section 170(c)(2)(B) and does not have, as a significant purpose, the production of income or appreciation of property.16

Section 4945: Taxable Expenditures

Private foundations are required to make grants for charitable purposes as defined in Section 170(c)(2)(B).17 Any amounts paid or incurred for the following other purposes are considered taxable expenditures:

- to carry on propaganda or otherwise attempt to influence legislation;18

- to influence the outcome of any specific public election, or to carry on, directly or indirectly, any voter registration drive;19

- to make a grant to an individual for travel, study, or other similar purpose unless the foundation has obtained advanced Internal Revenue Service approval for its grant-making process;20

- to make a grant to any organization that is not described as a public charity in Section 509(a)(1)

or (2) or is an exempt operating foundation, unless the foundation exercises expenditure responsibility with respect to the grant;21 and - to make a grant for any purpose other than one specified in Section 170(c)(2)(B).22

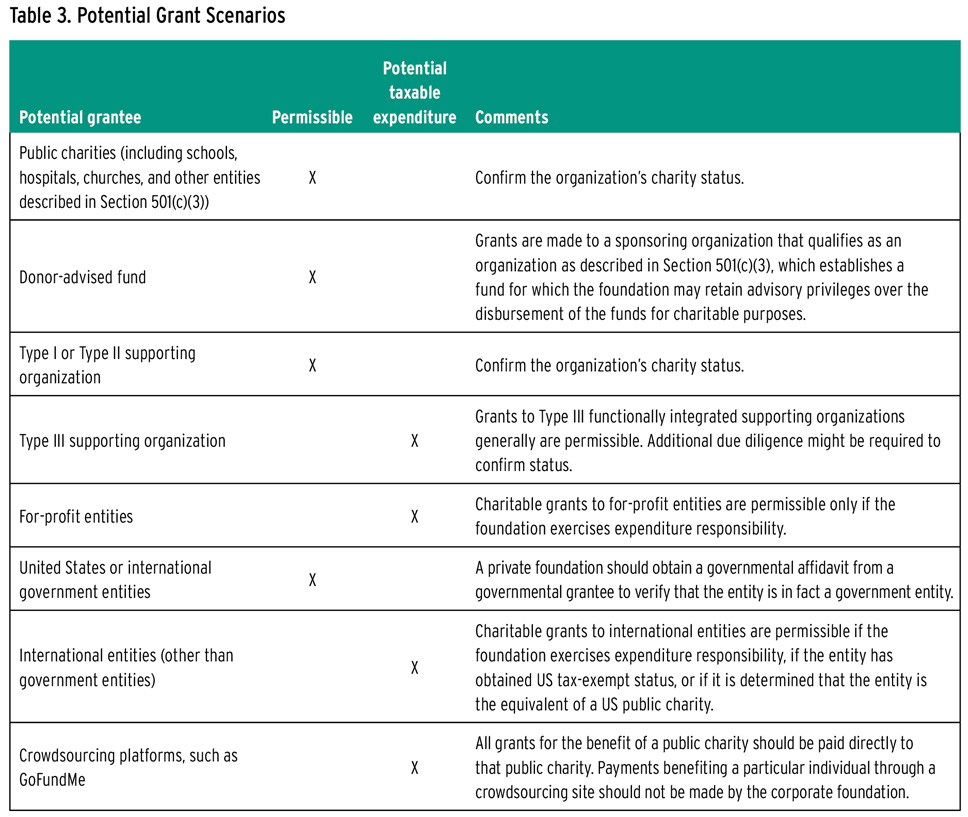

Due to this requirement, some private foundations will not make grants to any individuals or to any organizations that are not described in Section 501(c)(3) as public charities. However, this practice could curtail the private foundation’s ability to carry out its charitable objectives, particularly if they include scholarships or grants and charitable activities outside the United States.

Instead of imposing restrictive eligibility requirements, in-house tax professionals can help the foundation fulfill its charitable objectives by working with foundation personnel to put in place processes to accomplish these objectives while remaining in compliance with Section 4945. Good grant-making policies and procedures, developed using a risk-based approach to financial, operational, programmatic, and reputational risks, will permit the foundation to consider and make grants with an exclusive charitable purpose to organizations, including for-profit entities and international organizations, by exercising expenditure responsibility. In doing so, the foundation must exert all reasonable efforts and establish adequate procedures to ensure that its grants are spent solely to achieve their intended purpose, to obtain full and complete reports from grantees on how the funds are spent, and to make full and detailed reports regarding the grants to the IRS.23 Most foundations already have a grant-making process that meets many of these requirements, so the in-house tax professional can help to align those procedures with any added steps required under the related Treasury regulations. Table 3 identifies several grant-making scenarios with comments regarding permissibility under

Section 4945.

Other Regulatory Requirements

For corporate foundations making grants to non-US charitable or governmental organizations, additional steps should be added to the grant-making procedures to verify that making a grant to the non-US entity will not subject the corporate foundation to penalties imposed by Treasury. Grant-making procedures to non-US entities should consider reviewing:

- the Treasury’s “Anti-Terrorist Financing Guidelines: Voluntary Best Practices for US-Based Charities” notice;24 and

- the Office of Foreign Assets Control Sanctions Programs and Information.25

In addition, corporate foundations that receive any funding from a foreign government should discuss with their counsel whether they have any registration requirements under the Foreign Agents Registration Act administered by the US Department of Justice.26

A Word on Reputational Risk

One of the biggest risks companies and their corporate foundations now face is reputational risk. Reputational risk causes embarrassment and threatens both the foundation and the company. This risk can manifest itself in many ways, including affiliations with certain donors, affiliations with certain grantees, grants (or lack of grants) addressing a particular issue, and more.

Conclusion

Now more than ever, companies are expected to invest in society through their business activities and specific charitable efforts. As companies move away from responsive philanthropy to a more strategic approach, they need to rely on the experience of in-house tax professionals, along with outside advisors, to guide them and their foundations along the appropriate path. It can be a balancing act to mitigate regulatory risks while pushing the boundaries to improve the community around it.

Diane L. Kirmaci, JD, LLM, is a principal and Lori A. McLaughlin, CPA, PFS, is a partner at Crowe.

Endnotes

- Anna Koob, “Key Facts on US Nonprofits and Foundations, 2021,” Candid, June 17, 2021, https://candid.issuelab.org/resource/key-facts-on-u-s-nonprofits-and-foundations-2021.html.

- Internal Revenue Code [hereafter IRC] Section 4940(c)(2).

- IRC Section 4940(c)(1).

- IRC Section 4946(a)(1).

- IRC Section 4941(d)(1).

- IRC Section 4942(e)(1).

- IRC Section 4942(a).

- IRC Section 4942(g)(1)(A).

- IRC Section 4942(g)(1)(B).

- IRC Section 4945(d)(4).

- IRC Section 4942(i)(2).

- IRC Section 4943(c).

- IRC Section 4943(c)(2)(C).

- IRC Section 4944.

- IRC Section 4944(c); IRC Section 4943(d)(3)(A).

- IRC Section 4944(c).

- IRC Section 4945(d)(4) and IRC Section 4945(d)(5).

- IRC Section 4945(d)(1).

- IRC Section 4945(d)(2).

- IRC Section 4945(d)(3).

- IRC Section 4945(d)(4).

- IRC Section 4945(d)(5).

- IRC Section 4945(h); Treasury Regulations Section 53.4945-5(b).

- US Department of the Treasury, “Anti-Terrorist Financing Guidelines: Voluntary Best Practices for US-Based Charities,” Federal Register 71, no. 210 (October 31, 2006): 63838, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2006/10/31/06-8961/anti-terrorist-financing-guidelines-voluntary-best-practices-for-us-based-charities.

- “Office of Foreign Assets Control—Sanctions Programs and Information,” US Department of the Treasury, accessed June 28, 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/office-of-foreign-assets-control-sanctions-programs-and-information.

- “Foreign Agents Registration Act,” US Department of Justice, accessed June 28, 2022, www.justice.gov/nsd-fara.

Sidebar: Action Item

To mitigate the risk of self-dealing when assets or employees are shared between the company and the corporate foundation, the parties should consider a written shared services agreement to:

- document the roles and obligations of each party;

- provide a framework for allocating personnel costs so that the corporate foundation reimburses the company only for the provision of personal services allowable under the US Department of the Treasury regulations; and

- document the corporate facilities, equipment, and supplies that will be provided to the corporate foundation at no cost and list other provisions for confidentiality, intellectual property, and the like.

Sidebar: Action Item

A corporate private foundation should adopt a payout or spending policy to guide its charitable disbursements. Corporate foundations take different approaches to a spending policy: although some foundations pay out the minimum five percent requirement discussed earlier, others pass through most of their donations each year to charitable organizations. Thus, a private foundation should formalize its preferences in a written spending policy document for a consistent giving approach. The spending policy also can incorporate planning opportunities to manage cash flow, preserve assets, and maximize the use of excess distribution carryovers.

Sidebar: Action Item

Corporate foundations should adopt a written investment policy to guide the investment of the private foundation’s assets in a manner consistent with the fiduciary and prudent investment standards of the prudent investor rule and codified in the Uniform Prudent Investor Act of 1992, as well as to avoid potential excess business holdings.

Sidebar: Action Item

Before dismissing a potential charitable grant, consider whether the foundation may exercise expenditure responsibility on a potential charitable grant to meet its objectives. The foundation should consider developing a risk-based matrix to use as a tool for conducting due diligence and monitoring its grants. A risk-based approach to grant-making will:

- assess the likelihood and severity of future grant problems by reviewing grant risks (financial, programmatic, operational, and reputational) of each grant and grantee;

- tailor the grants’ due diligence and monitoring approach (for example, resources and scrutiny) to the identified risks of grants and grantees;

- manage the use of foundation resources (such as staff and financial resources) on those grants and grantees based on risk (in other words, not a one-size-fits-all approach) through a consistent grant-making approach; and

- manage grants and grantees effectively given both short- and long-term risks (including IRS compliance and grantee capacity building).

Sidebar: Action Item

Sidebar: Action Item

In-house tax professionals can assist a corporate foundation in crafting gift acceptance policies and grant eligibility guidelines to help the foundation mitigate potential reputational risks based on the organization’s level of risk tolerance.