On June 23, 2016, the United Kingdom voted in a national referendum on whether the UK should remain a member of the European Union. It was a simple in-or-out question asked of the British people, of whom 51.9 percent voted to leave the EU and 48.1 percent voted to remain. The consequences of this so-called “Brexit” vote will shape the future of the UK for perhaps a generation or more.

The UK has been part of the EU (originally the European Economic Community, or EEC) since January 1, 1973. Membership in the EU has had a major impact on the UK’s ability to trade with the rest of the EU. The founding treaties are based on four so-called fundamental freedoms: free movement of goods, free movement of persons, free movement of services, and free movement of capital. These fundamental freedoms and other rights and obligations of EU membership are laid down in various EU treaties and secondary legislation such as EU directives and regulations.

The single market created by the EU has greatly facilitated trade between EU member states as well as the free movement of travelers and workers. Since joining the EU, the UK has opted out of certain obligations of EU membership. For example, it is not a member of the eurozone and so does not share the EU’s common currency. It is also not party to the Schengen Agreement, which allows free movement of persons, with no border controls, between most EU member states (the exceptions being Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Ireland, Romania, and the UK) and a few non-EU States: Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein.

Following the referendum and a vote in the UK Parliament, on March 29, 2017, the UK government gave the European Council formal notification under Article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon of the UK’s intent to withdraw from the EU. It is still uncertain when the UK will formally exit, but Brexit is anticipated to happen by March 2019, two years after the UK’s Article 50 notification. Paragraph 3 of Article 50 provides that “The Treaties shall cease to apply to the [withdrawing] State in question from the date of entry into force of the withdrawal agreement or, failing that, two years after the notification referred to in paragraph 2, unless the European Council, in agreement with the Member State concerned, unanimously decides to extend this period.” The remaining member states have made it clear that they wish to agree to the formal process for the UK leaving the EU (which will identify how much the UK must pay into the EU budget for previous commitments) before the UK is entitled to agree to any form of trade deal with the remaining member states.

The exact mechanism for a member state’s exit from the EU under Article 50 is unprecedented, and much remains uncertain about how the withdrawal process will unfold. This article will focus on how the UK’s exit from the EU will affect indirect tax in the UK and will consider the changes to value-added tax (VAT) and customs duties that Brexit might bring. Currently, the operation of both VAT and customs duties in the UK depends wholly on EU law.

The UK government has said, “At the heart of [the referendum] decision was sovereignty. A strong, independent country needs control of its own laws. That, more than anything else, was what drove the referendum result: a desire to take back control.”1 Whether a desire to reclaim sovereignty truly was in the minds of those who voted to leave the EU, it will undoubtedly be the issue of greatest impact for the UK upon leaving the EU. This will be acutely apparent for the operation of both VAT and customs duties, and to a certain extent other indirect taxes such as excise duties, which are all taxes charged on the supply and movement of goods and the supply of services within and beyond the EU.

Supremacy of EU Law

When the UK joined the EEC (which subsequently became the EU), Parliament gave supremacy to EU law insofar as rights and obligations were created by the UK’s membership in the EU.2 The supremacy of EU law and the UK’s requirement to adhere to decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) will end upon Brexit. This will leave a huge gap in the UK’s legislature, and so the UK government intends to incorporate existing EU law into UK law at the moment the UK leaves the EU. The UK government has also said that the decisions of the CJEU up to the point of Brexit will be binding on UK courts in the same way that decisions of the UK Supreme Court are. The effect will be that the CJEU judgments that have been delivered up to the point of the UK leaving the EU will be binding on UK courts, unless and until the UK Parliament legislates to neutralize or vary the impact of any particular decision of the CJEU.

The Conservative Party Prime Minister, Theresa May, has called an election, she says, “to guarantee security for years ahead” and no doubt she will be hoping to increase the Conservative Party majority in Parliament, which she hopes will enable her “to make a success of Brexit.” Before the government called an election to be held on June 8, 2017, the UK had set out in a white paper3 the framework for achieving a smooth transition from the UK’s membership in the EU to its place in the world outside the EU. In short, the UK intends to enact legislation that will repeal the European Communities Act 1972, the legislation that gives effect to EU law within the UK. The “Great Repeal Bill,” as this proposed legislation has been labeled, is a bit of a misnomer, as it will also actually incorporate the existing body of EU law (known as the “acquis”) into UK law. It is said that by so doing, it will allow businesses to continue operating, knowing that the rules have not changed significantly overnight, and provide fairness to individuals, whose rights and obligations will not be subject to sudden change. The idea is that this new legislation will ensure that it will be up to the UK Parliament (and, where appropriate, the devolved legislatures) to amend, repeal, or improve any piece of EU law (once it has been brought into UK law) at the appropriate time once the UK has left the EU. If the Conservative government is reelected in June 2017 with a majority in Parliament, then we can assume that this legislation will be passed and will enter into law. This, however, is only the beginning, laying the groundwork for the UK to exit the EU. As we discuss below, the real issue is what (if any) trade deal the UK manages to secure with the EU. Before we discuss this, however, it is important to understand how the EU, and EU law in particular, impacts VAT and customs duties in the UK.

Harmonized Indirect Taxes System Within the EU

Customs Duties

The EU is both a customs union and a single market. As a customs union, there are no customs duties on the movement of goods within the EU’s territory, and member states share common external tariffs with third countries. Customs legislation is laid down in EU regulations that are directly applicable in all member states without the need for national implementing law. If a question is raised by an individual business as to the meaning of customs legislation (for example the meaning of a tariff classification of a particular product which is being imported into the EU or the legal basis for a particular customs operation), the EU treaties require the national court in the relevant member state to refer any questions over the interpretation or validity of EU law to the CJEU. The CJEU’s decisions are binding on all member states in order to ensure a uniform interpretation and application of EU law throughout the EU.

VAT

As a single market, the EU operates a harmonized VAT system that is charged on a consistent and integrated basis across the whole of the EU’s territory. Although direct taxation is left to the member states to determine (subject to the obligation not to tax in contravention of the four freedoms), VAT is very much a harmonized tax within the EU. EU directives are agreed upon by EU member states, and those directives must be applied (transposed) by the member states and incorporated into their national law. The so-called Principal VAT Directive (PVD) lays down in very precise detail how member states are to apply VAT. By way of example, the PVD sets down, among other detailed provisions, what should appear on a VAT invoice; the definition of a taxable person for the purposes of applying VAT; what services are eligible for VAT exemption; that the minimum rate of VAT must be fifteen percent; and that there can be no more than two reduced rates for certain goods and services, neither of which can be lower than five percent.

That said, the UK has been allowed certain derogations since it joined the EU. For example, the UK is entitled to apply zero-rates to certain goods and services such as certain foods, but it is not entitled to expand that list of zero-rated items. Accordingly, the UK has limited powers to change or adapt the UK VAT system. The only way that the EU VAT system can be changed is by unanimous agreement with the other member states to pass new EU law on the subject. This is a long and cumbersome process and cannot be achieved at all without unanimity. For example, the UK has been campaigning to modernize the VAT exemption system for financial services for many years, but without success, because the member states cannot agree on what changes should be made.

As set out above, EU countries must transpose EU directives into national law to achieve the objectives set by the directive. National authorities must communicate these measures to the European Commission. Transposition into national law must take place by the deadline set when the directive is adopted (generally within two years). When a country does not transpose a directive, the Commission may initiate infringement proceedings, which may culminate in a hearing before the CJEU to decide whether the member state in question has properly transposed the relevant directive into national law. The idea is that the CJEU, as guardian of the rule of law within the EU, can ensure that member states fully observe the objectives set by EU treaties.

In addition, individuals and businesses are also able to ensure that member states comply with EU law because they are entitled to rely on the wording of a directive, once the time limit for the member state to implement the directive has passed and the provision in the directive is sufficiently precise and unconditional (in such circumstances the directive in question is said to be “directly effective”). Direct effect means that individuals or businesses may rely on the terms of the directive instead of conflicting national legislation or practice. If the meaning of a directive is in question during legal proceedings in which a national court is required to give judgment, that court can refer the matter to the CJEU. The decisions of the CJEU are binding on all member states so that EU law can be consistently applied in the courts and by the authorities of the member states themselves. Thus, when a taxpayer challenges a local VAT decision in a particular member state through the national court, and where there is a question as to the interpretation of the PVD, the court should refer the question to the CJEU. This condition has meant that the CJEU has given many decisions over the years that have significant impact on the interpretation of EU VAT law and the laws of the member states. It is a principle of EU law that national member state legislation that implements a directive should be read, so far as possible, in a manner consistent with the directive or, where the national law conflicts with the directive, the national law has to be rendered invalid. Accordingly, one can see that the EU, and EU law in particular, has had a significant impact on the operation of many laws in the UK, and on VAT in particular.

Although following Brexit it would be possible for the UK to overhaul UK VAT and replace it with an entirely different system, the cost to business is likely to be too great, and the VAT system is widely considered to be a relatively efficient and effective way of raising national taxes.

Trade Negotiations

It is likely that different sets of negotiations will be required to establish the nature of the UK’s relationship with the EU post-Brexit. Ultimately, the aim is for the UK’s future trading position with the EU to be determined by way of a new EU-UK Free Trade Agreement (FTA). This is separate from the withdrawal agreement, which should be limited to the consequences of the UK’s exit from the EU—for example, how much the UK may have to pay into the EU budget to extricate itself from the EU. A transitional arrangement might also be sought to bring clarity to the terms of trade between the UK and the EU until a new FTA (if any is agreed upon) comes into force. It is further likely that separate international agreements between the UK and the remaining twenty-seven EU member states will be sought covering other aspects of international law including security, defense, and, possibly, some aspects of joint foreign policy.

Three main issues must be determined in the trade negotiations: (1) whether the UK seeks to be outside the EU customs union; (2) whether the UK can maintain full access to the EU single market; and (3) to what extent can limitations upon immigration (especially on free movement of people) be achieved.

We have set out below a number of models on which Brexit negotiations could be based, although the UK government has so far said that it does not want to follow existing models for any trade agreement between the EU and third countries and wants instead to achieve a bespoke agreement with the EU:

- Remain a member of EU Customs Union. Remaining in the EU Customs Union would mean that goods would not (in principle) be subject to tariffs or border controls upon crossing from the UK into the EU and vice versa. There would be more formalities and potential barriers to trade, although these would be minimal as the UK currently complies with EU standards for products. Although all goods exported to the EU would need to comply with relevant EU legislation, they would not be subject to the “rules of origin” (see below). However, remaining a member of the customs union would compromise the UK’s ability to negotiate its own FTAs with third countries. It is likely that the UK would also have to comply with the judgments of the CJEU insofar as they affect the EU’s customs union, which would then affect the government’s stated aim of taking back control of its laws.

- Seek membership in the European Economic Area (EEA). The EEA model would provide access to the EU single market for a wide range of qualifying goods and services. It would also allow the UK to negotiate its own FTAs with third countries independently. However, membership in the EEA would require the UK to accept the principle of the “free movement of people.” Exports and imports between the UK and the EU would also be subject to customs formalities. The EEA establishes its own “rules of origin” (i.e., the criteria for determining the national origin of a product) to prevent circumvention of tariffs by, for example, importing products from third countries at tariffs lower than the EU tariff and then shipping them to EEA countries tariff-free. Customs duty exceptions and exceptions from quantitative restrictions would apply only to goods “originating” in the EEA. In addition, the UK would have to pay to be a member of the EEA.

- Reliance on World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. The WTO rules would likely be a fallback position if the UK exits from the EU without a trade agreement. Although reliance on WTO rules would give the UK the freedom to negotiate its own FTAs, it is not desirable, as tariffs would be reimposed on trade in goods between the UK and the EU. The effects would be felt particularly in areas where average tariffs are high (such as agriculture and food products, clothing and textiles). The reintroduction of customs inspections of goods crossing the EU/UK border would be a significant administrative burden and could slow down trade flows to and from the UK. Although a form of “transitional arrangement” is possible as part of the Brexit agreement, there is a material risk that there will be a period during which WTO tariffs will apply to the import and export of goods between the UK and the EU, until an EU-UK FTA (if any) is agreed upon. The WTO rules are also quite tricky for the UK to fall back on. Under the WTO agreements, countries cannot ordinarily discriminate among their trading partners. Accordingly, if the UK were to grant the EU a special favor (such as a lower customs duty rate for a single product), then the UK would have to do the same for all other WTO members, under the principle known as most-favored-nation (MFN) treatment. As the WTO itself states: “In general, MFN means that every time a country lowers a trade barrier or opens up a market, it has to do so for the same goods or services from all its trading partners—whether rich or poor, weak or strong.”4

Potential Impact of Brexit on VAT

Businesses that are registered for VAT in the UK and all businesses that supply services and move goods to or from the EU will be concerned about how Brexit might affect their operations. Too much rests on what the post-Brexit relationship between the UK and the EU would look like to predict with any accuracy the exact impact to businesses. Although following Brexit it would be possible for the UK to overhaul UK VAT and replace it with an entirely different system, the cost to business is likely to be too great, and the VAT system is widely considered to be a relatively efficient and effective way to raise national taxes. It is likely, therefore, that VAT will remain largely consistent with the current EU system in order to facilitate any trade agreement between the UK and the EU.

However, there are several areas, some described below, where the UK might want to depart from the current EU model or may have to adapt its model post-Brexit to avoid a potential loss of tax.

- VAT rates and VAT liabilities. The UK has benefited from the zero-rating of certain products and services (e.g., certain food items) and may want to extend this benefit to more goods and services post-Brexit. The UK would also be in a position to reduce VAT rates or extend the list of goods and services that qualify for VAT exemption or reduced VAT rates. The UK has already demonstrated that its view of how VAT law should be interpreted in relation to exempt supplies is, in certain limited respects, at odds with that of the EU. For example, the cases of Arthur Andersen (Case C-472/03) and Aspiro (Case C-40/15) both held that back office activities provided in the insurance sector did not qualify for the VAT exemption for insurance services under EU VAT law. So far the UK has not sought to implement these CJEU decisions into UK law. Accordingly, the UK’s interpretation of the VAT exemption for insurance services remains somewhat wider than that permitted under the PVD, according to the CJEU. Conversely, the UK will have to make changes to other financial services exemptions before Brexit to ensure that UK investment managers can benefit from the VAT exemption which applies to the management of certain special investment funds, including certain types of pension fund and property fund, the management of which has been subject to UK VAT and which, according to the CJEU, should be VAT-exempt.5

- MOSS and digital services. In 2015, the EU introduced the Mini One Stop Shop (MOSS) regime, which allowed UK businesses selling telecommunications, broadcasting, or electronic services to consumers to account for VAT due in other EU member states through a single UK portal. Similar rules apply in the other EU member states. When the UK leaves the EU, it is likely that UK businesses selling relevant services to consumers in EU member states will either have to register for VAT in each relevant member state or register under a non-Union MOSS facility administered by another member state.

- VAT groups. Recent CJEU case law6 has shown that the UK’s VAT group rules do not comply fully with EU law. The CJEU case Skandia America Corporation (Case C-7/13) highlighted how different EU member states treat VAT grouping differently, which can adversely affect competition between member states. Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs has announced that it will review its VAT grouping legislation in light of this case law. The relevant legislation is not directly effective, so the UK is not bound to make any changes, and post-Brexit it may decide not to do so. Again, we suspect that any changes will depend upon the trade deal, if any, that the UK reaches with the EU.

- Place of supply. The EU VAT system operates broadly to ensure that VAT is collected in the country of consumption. The UK will have to amend areas of UK VAT legislation which refer to the EU and the Community, as well as other references to supplies between member states, to ensure that the UK does not lose tax. For example, most financial services that are supplied by providers (such as EU banks and financial institutions) to consumers in the EU are VAT-exempt. Although the consumer does not have to pay VAT on the services provided, the providers have higher costs because they are not entitled to deduct the input VAT on costs associated with supplying those services. Conversely, the PVD permits EU financial institutions to recover input VAT on supplies of most financial services provided to consumers outside the EU without charging them VAT (an effective zero-rate), thereby encouraging those outside the EU to use the EU’s financial services providers. However, as UK law currently stands, when the UK leaves the EU, a French bank, say, will be able to zero-rate its services to UK consumers, theoretically making it cheaper than the same service provided by a UK bank. One would expect the UK to change the UK law pre-Brexit to ensure that anomalies of this sort are ironed out.

At the moment it is very difficult to predict on what basis trade between the UK and the EU will occur post-Brexit.

Potential Impact of Brexit on Customs Duties

One area where tangible post-Brexit consequences will be felt most acutely is customs duties and border controls on goods entering and leaving the UK. At the moment, it seems highly likely that upon leaving the EU, the UK will cease to be part of the customs union. The EU alone negotiates trade agreements between the EU and third countries, and member states cannot negotiate unilaterally. Although while outside the EU the UK will be free to negotiate its own FTAs, the time and cost of achieving these agreements will be significant and potentially quite complex because of the MFN principle discussed above.

If the UK does leave the EU Customs Union, a system of border controls between the UK and the EU will be necessary. The same formalities required for goods entering the UK from outside the EU will be required for UK goods entering the EU. This will have a major impact on the flow of goods cross-border and the ability of global businesses to move goods across the EU as part of a manufacturing process. Famously, the manufacture of cars in the EU requires various components to be manufactured and to be moved back and forth between member states before the car is assembled and ready for sale. The introduction of border controls will increase the costs and time to do this and is likely to greatly hinder the import and export of goods into and out of the UK. For this reason, it is hoped that the UK can negotiate some sort of free trade deal with the EU that allows it to move goods across borders without customs formalities or tariffs.

Conclusion

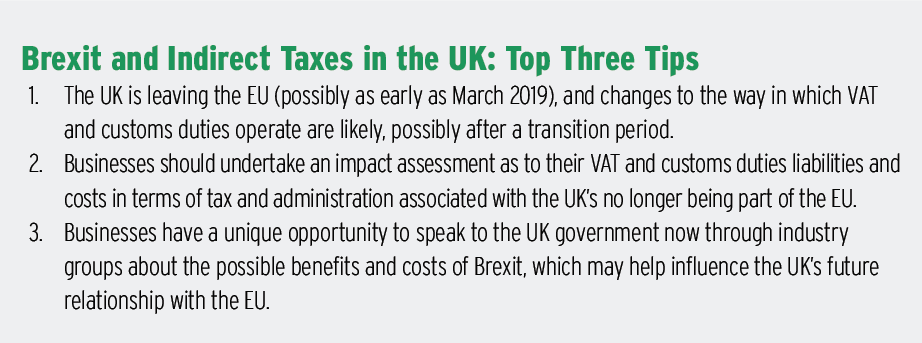

At the moment, it is very difficult to predict on what basis trade between the UK and the EU will occur post-Brexit. Of course, the result is highly political, and the EU has made it clear that it will not discuss the subject until the terms of the UK’s exit from the EU are settled. If this occurs, it is likely to be some years before we see any cohesive system emerge. One can only hope that the parties agree to a transitional period which will allow businesses to carry on as they are doing for now. Change will come eventually, and it is likely that indirect taxes, particularly customs duties and VAT, will change or adapt to the new regime. The extent of this change will inevitably depend on the nature of any trade deal between the UK and the EU. Until then, business will be left in a state of uncertainty as to what the picture will look like. This may affect third-country investment in the UK and may encourage those investors to look to the remaining EU member states so as to benefit from the EU trade bloc rather than to reach that market via the UK. It is therefore difficult at this stage for business to plan. However, many global businesses across all sectors are actively planning for the possible costs and benefits of Brexit and are no doubt lobbying to ensure that a good outcome is achieved.

Giles Salmond is a partner and heads the indirect taxes and tax dispute resolution practices at Eversheds Sutherland (International) LLP.

Giles Salmond is a partner and heads the indirect taxes and tax dispute resolution practices at Eversheds Sutherland (International) LLP.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not those of Eversheds Sutherland (International) LLP.

Endnotes

- See foreword by David Davis MP, the Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, to “The Great Repeal Bill: White Paper” (March 30, 2017) www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-great-repeal-bill-white-paper.

- Such rights and obligations are derived from the European Communities Act 1972. Section 2(1) states: “All such rights, powers, liabilities, obligations and restrictions from time to time created or arising by or under the Treaties, and all such remedies and procedures from time to time provided for by or under the Treaties, as in accordance with the Treaties are without further enactment to be given legal effect or used in the United Kingdom shall be recognised and available in law, and be enforced, allowed and followed accordingly; and the expression [‘enforceable EU right’] and similar expressions shall be read as referring to one to which this subsection applies.”

- “The Great Repeal Bill: White Paper” (March 30, 2017).

- See World Trade Organization website link, “Principles of the Trading System,” www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/fact2_e.htm.

- See, for example, the CJEU judgments in Case C-464/12 (ATP PensionService, which held that the management of a defined contribution pension scheme is VAT-exempt) and Case C-595/13 (Fiscale Eenheid X, which held that the management of a property fund is VAT-exempt).

- In July 2015, the CJEU released its judgment in the joined Cases C-108/14 and 109/14 (Larentia + Minerva and Marenave, respectively) which held that EU member states may restrict VAT grouping only to legal persons, when those restrictions are appropriate and necessary to prevent abuse, avoidance, or evasion