In the world of real estate, it’s all about location, location, and location. In the tax world, it is becoming all about data, data, and data. And whatever facet of tax technology you’re talking about—whether it’s hardware, software, Big Data, the cloud, data storage, or cybersecurity—the data are the key drivers.

Especially in the last decade, the relationship between tax and data has helped to produce technological advancements that have created a tidal wave of changes for the corporate tax executive.

One of the biggest changes in the tax technology space has been the rate of change, according to Stephen McGerty, head of OneSource indirect tax technology at Thomson Reuters. Increased regulatory requirements and technology advancements are both evolving more rapidly than ever before, he says. For tax professionals, this means adapting to two constantly shifting landscapes, both of which they need to stay plugged into, McGerty asserts.

Tax technology has evolved and elevated the job for tax professionals who embrace and harness it. The analytics and insights provided by tax technology can give tax professionals a seat at the corporate table and help prove their strategic value, McGerty says.

New technology unlocks the value of data. “It used to be that we did a return, put it away, and only revisited it to defend an audit. Now, technology allows us to use that data and extract more value—for scenario planning, for example, or for identifying trends we didn’t see before,” he explains.

But there are complications. Tax applications to date have been purpose-built, says Jennifer Kurtz, principal architect at Vertex Inc. They are designed to meet particular needs within the tax life cycle, and each application is different. “They are independent applications, making it difficult to move the data between these systems and through the entire tax life cycle,” she says. Today, the movement of tax information is accomplished through a series of complex integrations at the data level. “Extracting data for tax applications from financial systems has also been a challenge, since the information needed may not be reflective of the needs of tax and more so of the management structures,” Kurtz added.

“Multinational organizations must be able to distinguish between commercial data management and tax data management and use the appropriate data set as the foundation for their tax planning, compliance mechanisms, and reporting,” —Kim Majure

So if data is the fuel in the tax technology revolution, what’s the new technology engine? The emergence of software specifically built and designed for tax departments, jurisdictions, and authorities has revolutionized the corporate tax space. Specifically, the development of a vast array of software applications, combined with the evolution of data management, integration, and access, has shaped the expectations and real-world experiences of tax technology users, not only in the United States but all around the globe.

Indeed, notes David Deputy, director of tax data management at Vertex, jurisdictions outside the United States are playing major roles in tax technology. What Brazil and China have done—creating systems for all transaction details rather than asking for summary data filed in returns—is the future in tax technology. “The jury is still out on whether the governments will provide the calculation, as well as the storage, of post-calculated data results. The cloud makes either option doable at a reasonable cost today. The cloud also enables the government to become a ‘tax as a service’ provider directly and demand all your detailed data all the time,” he explains.

Software offerings in the cloud allow for integration between systems, making true automation possible, notes McGerty. “Cloud offerings, as opposed to on-premises offerings, allow us to deliver updates, changes, and improvements to all of our customers in real time,” he says.

Brad Hearn, head of Tax Product Management Longview Solutions, agrees that the emergence of the cloud sits at the center of the technological revolution. The cloud “promotes a vision of a landscape that serves as an ecosystem of best-in-breed solutions, tightly connected and sharing data seamlessly between one another,” he says. That underlying infrastructure is what drives much of the conversation around Big Data and analytics, recognizing that, with so much information at our disposal, new tools are needed to understand and interpret it, explains Hearn.

Deputy echoes Hearn’s take on the cloud and Big Data: The combination of the cloud and Big Data is far and away the most important development in tax technology. “Computing is now a utility like power, and tax is now beginning to understand how to create the appliances (i.e., apps) to harness this power. We are at the very beginning of this major shift. Right now we are defining the base layer, the engine to power tax performance. Once that is complete, the applications will start proliferating much as they did on the iPhone, and productivity will increase dramatically as a result,” he says.

Kurtz also emphasizes the impact of Big Data and the cloud. Both the cloud and Big Data will propel the current generation of tax solutions into enterprise-level software. The cloud will continue to evolve and become more widely adopted by more and more corporations that want to leverage tax applications that will use fewer resources and reduce maintenance costs and efforts, she says.

“The number of data encryption and multifactor authentications are also advancing cloud-based technology. A benefit is that tax departments do not have to be reliant on in-house IT departments, where tax may not be seen as ‘mission critical,’” Kurtz explains. Additionally, she says, since many business applications are moving to the cloud, integration technologies to move data between systems managed by clients and systems residing in the cloud are getting a lot of focus and becoming more robust, faster, and more secure as a result.

If this is the beginning of a revolution in tax technology, are these tectonic shifts good for all tax practitioners? Are dangers present or lurking for taxpayers in the dizzying pace of technological change? It is a subject explored in many of its dimensions by TEI tax executives and professional advisers at multiple forums, including, most recently, in Washington, D.C., at TEI’s 65th Midyear Conference and in Munich, Germany, as part of a Corporate Tax Executives workshop. This article draws on and expands upon those conversations to explore key perspectives on the new technology—both its benefits and risks.

Impact on TEI Practitioners

Hearn says there’s no looking back when it comes to tax technology: As we see how tax technology trends are affecting the expectations of buyers, the mindset of tax professionals is continuing to evolve, embracing a focus on data. “We believe having a data management platform specifically designed to be owned and operated by the tax department will prove to be immensely powerful and deliver tremendous benefit to the tax function,” he says.

So, how does it affect the daily activities of TEI’s tax practitioners? According to Deputy, technology removes the need to ask IT for access to data by moving the tax professional to a more self-service data access and analysis mode. “Technology also enables users to continue to utilize Excel for the presentation of data but separates data storage and calculation, moving them into a secure, auditable central system. The net result is that users keep tools they know and are comfortable with, which in the end means they can work much more efficiently with a higher quality of outcome,” he explains.

Technologies that leverage Big Data, analytics, and application programming interfaces (APIs) allow for this now, and tax technology providers are creating solutions this way, adds Kurtz. In some cases, this will change the way tax looks at information, moving from working with data from the past and at a summary level, to working with that same data in more detail and leveraging analytics to make strategic choices about the future. It also means finding ways to change the upstream processes that impact tax and to automate the organization of data for tax purposes.

While we expect that comprehensive data management will demand increasing focus from the corporate tax professional, technology is currently impacting everyday jobs in a more specific fashion, says Longview’s Hearn. Today, most tax departments have installed compliance applications or outsourced this function to service providers who take advantage of the same (or similar) technologies. With many tax authorities now requiring electronic submission of data, this has further driven adoption, he adds.

More states, for example, are requiring electronic filings. For sales and use taxes, about thirty-eight percent of the states required electronic filing in 2005. Today, sixty-three percent of the states mandate electronic filing, Deputy notes.

However, Hearn concludes, “while electronic filings have moved the related activities from pencil and paper to keyboard and computer, it has not materially impacted the day-to-day activities of the corporate tax professional.”

But when you look closely at tax accounting, and the preparation of quarterly and annual provisions, there’s a much different landscape, according to Hearn. Most tax departments continue to leverage Excel as the primary technology used to calculate provisions. “For those that have looked beyond Excel and have worked to incorporate tax technology into this function, they are seeing significant impacts in their day-to-day focus and ways of working,” he explains.

“Extracting data for tax applications from financial systems has also been a challenge, since the information needed may not be reflective of the needs of tax and more so of the management structures.” —Jennifer Kurtz

In this context, Hearn says, tax technology is affecting the corporate tax executive in three significant ways:

- Greater visibility and clarity into results

- Reduction in reporting times and efforts

- Improved predictability and confidence

By moving from a disparate, Excel-based world to centralized, database-driven applications, the data used to compute tax provisions becomes better organized. “This, in turn, facilitates analysis and allows the corporate tax department to gain greater visibility and clarity into what is driving a particular result metric. This also allows the tax function to employ automation in the process and greatly reduces the amount of time often consumed with low-value data retrieval and reconciliation efforts,” Hearn explains.

Not only can this reduce the overall time to completion, it also allows tax professionals to shift their focus to reviewing the results and truly analyzing and monitoring the process. “This, coupled with the reduction of risk inherently associated with managing the provision process solely in Excel, drives increased confidence in the final results,” Hearn concludes.

The Email Trail

Thomson Reuters’ McGerty also cites the changes to email brought about by the new technology. “In the past you might send fifty emails to gather information from colleagues and then spend an entire afternoon stitching that information together in a report. Data collection tools now put that information into a template that makes the process much faster,” he explains.

“The jury is still out on whether the governments will provide the calculation, as well as the storage, of post-calculated data results. The cloud makes either option doable at a reasonable cost today.” —David Deputy

What are the major benefits of the new technology? Deputy, Kurtz, Hearn, and McGerty cite these advantages:

- Spending more time with your family

- Working on high-skilled tasks rather than being a data janitor doing cleanup work

- Collaborating with colleagues globally in real time rather than waiting on email responses

- Reducing significantly the manual efforts associated with data collection

- Shifting focus from nonvalue activities to areas such as review, analysis, investigation, and planning

- Strengthening controls and significantly reducing the risks associated with Excel-based processing and the likelihood of errors or incorrect results

- Establishing a foundation of organized data that is a prerequisite to adopting analytics within the tax function

- Facilitating a mindset shift from organization and calculation of historical results to strategic analysis and prediction of possible outcomes

- Defending audits through better organization of data

- Creating increased bandwidth to provide greater strategic value to finance organizations

- Gaining access to detailed data unattainable in the past

- Drilling down into data at a level of granularity that was not previously available due to time and cost

- Using analytics and business intelligence tools to get insight to data faster through the use of visualization now at a greater level of detail for tax

In addition to these benefits, the new tax technology offers several intriguing possibilities. For example, Deputy says, the new tax technology can:

- Move your culture to a data-driven one, with the opportunity to vastly reduce manual efforts and waste

- Use analytics to stay ahead of the government that will be doing the same to spot risk areas for auditing you

- Share analytic routines that work for you with other companies; share logic, not data; and help build capacity on the corporate side to deal with the “sea change in transparency” washing over us

New tax technology creates opportunities by putting the tax function in a different context, explains Hearn. As the lens on tax grows and heightened focus and awareness of the tax function expands, tax departments are being called upon to interact with the wider organization in dramatically different ways than they’ve experienced historically, he explains. Other departments are increasingly asking the tax group to provide input and guidance into the strategic decision-making process as recognition expands that tax implications can materially impact outcomes.

The new tax technology can help develop a corporate culture that embraces technology and looks for ways to optimize or drive value through the adoption and application of tax technology. “As demands grow on the tax department and staffing remains lean in the overall corporate landscape, the need to become more efficient and better focused expands,” Hearn says. Companies that aim to leverage technology to relieve constraints will be better positioned than those that look solely at human- and resource-based solutions.

Increased accuracy is another opportunity provided by new technology, according to McGerty. Workflow tools and other technologies reduce human errors that were more common when everything was managed manually in spreadsheets. Regulatory updates that are built into these tools make sure teams don’t miss a rule change. Accuracy, especially in light of increased regulatory scrutiny, is critical.

However, the new technology is not without risk. For Hearn, changing existing processes inherently involves risk. However, he says, in today’s world, standing still often involves more risk. Identifying the risks associated with actions and determining how these can best be mitigated should be the focus. He cites these potential risks:

- Selecting the wrong technology

- Choosing an inadequate implementation partner

- Struggling to create a reasonable timeline

- Not finding enough time to commit

Big Data = Big Leverage

Hearn provides further explanation of the risk in choosing the best implementation partner. One of the first and most impactful decisions a tax department makes when embarking upon a technology transformation is determining with whom to partner. This typically begins with selecting a technology vendor but closely thereafter involves defining an implementation partner. Most technology vendors operate in-house professional services teams focused on helping organizations install and enable their technology. Several service providers have also established groups within their consulting practices that focus specifically on technology adoption. For tax departments, options include using one or even both of these groups, he says.

Currently, he adds, most tax departments are relatively inexperienced with the process of evaluating technology vendors and implementation partners. Often they also lack strong relationships with their finance/IT colleagues, who have amassed experience in this area over the last ten to fifteen years.

Service providers and implementation partners should be evaluated in the same light, as they also bring unique perspectives and approaches to the process. Ultimately, Hearn explains, finding a company that will spend the time to understand your vision and work with you to achieve this desired outcome is most critical, and having a strong partnering relationship as the backdrop will assist in overcoming the challenges that arise along the way.

For Kurtz, the major risk of new technologies for tax is not so much the technology or solutions but the change in management necessary to support this transformation of the tax function. New technology can disrupt existing processes within the tax department. The risk is not looking at both the processes and technology when considering tax technology transformation projects, according to Kurtz.

Dicker’s Take

Few would dispute that the specter of technology and technological innovation is everywhere, presenting myriad options and opportunities for the tax business community and its executives. While technology is everywhere, the pace and scope of technology adoption varies widely from company to company—and even within a company itself—not to mention across industries and geographies, notes TEI Executive Director Eli Dicker.

One modest measure of the growing interest of Institute members in the role technology may play in their work is the increasing number of educational programs being developed that focus on technology topics. “This suggests that in-house tax professionals are sensing the need to become more tech-savvy and to better understand technology trends and how available tools may help facilitate their work,” Dicker adds. These outreaches reflect, in part, the growing internal pressure to become more efficient, to produce more varied and sophisticated analyses more often and more quickly.

While tax technology undoubtedly can raise productivity of an internal tax group, Kimberly Majure, principal at KPMG LLP’s Washington National Tax office, warns that taxpayers will also need to consider the potential risks and limitations of technological solutions. She offers several scenarios below to highlight a few of the practical and strategic issues with tax technology.

Data Management Isn’t the Same as Tax Data Management

Corralling information and throwing it into an Excel spreadsheet is half the battle with tax compliance, particularly for companies with a very high volume of cross-border transactions and resulting tax items. “Multinational organizations must be able to distinguish between commercial data management and tax data management and use the appropriate data set as the foundation for their tax planning, compliance mechanisms, and reporting,” Majure explains.

“It used to be that we did a return, put it away, and only revisited it to defend an audit. Now, technology allows us to use that data and extract more value—for scenario planning, for example, or for identifying trends we didn’t see before.” —Stephen McGerty

Case in point: Consider an organization’s vendor accounts. Those accounts are meant primarily to track information regarding payees, then to memorialize the history of the organization’s payments (invoice date and payment date). Many companies use foreign vendor accounts to gather data for their Form 1042 and 1042-S filings. After all, the basic payment and payee information is readily available in the AP system, and vendor accounts also contain basic information regarding the character of payments made.

However, organizations should not simply take the data from a calendar year AP run and roll it onto a Form 1042-S. First, most vendor accounts only permit a company to indicate one type of income per account. In fact, the choices are often limited to sales or services payments. There is limited or no ability to reflect payments of royalties, rentals, interest (e.g., on late payments), or mixed payments (e.g., sales plus installation services) at the account level. There is certainly no ability to distinguish between U.S. source payments that are subject to Chapter 3 withholding and reporting when paid to a foreign vendor and foreign source payments that are not. That analysis must be done at the individual invoice level, particularly for services fees. This can be accomplished by a manual review or through word-recognition software; companies just need to understand that the necessary analysis is not being done at the account level.

An organization may currently be characterizing its cross-border payments, but who is making those determinations? As a general proposition, that function is not likely to be taken on by tax people. Most often, the vendor account folks are in charge of designating the types of payments being made, perhaps based on a cursory review of a contract or initial invoice. In addition, vendor account personnel are likely making their designations using commercial lingo, not tax language. Nonetheless, many tax directors are using the vendor account information not only to prepare the Forms 1042-S (i.e., assuming a single type of income and a single source) but also to make the initial, organization-wide determination whether to obtain any withholding documentation (e.g., Form W-8) from a foreign vendor or to track that foreign vendor’s payments. Once set, those types of decisions are seldom revisited. The organization’s technology effectively becomes a “Chinese wall” between the data and the tax director and can lead to unpleasant surprises during a subsequent audit. Tax directors are best advised to take a close look at their current systems and bridge the gaps between commercial and tax data, then incorporate those bridges into their technology solutions going forward.

Not All Spreadsheets Are Equal

As discussed, foreign tax examiners are beginning to use a Big Data approach to information, requesting tax-relevant information outside of the tax return and looking for patterns and trends that will put a company’s tax-return positions into context. While the mere fulfillment of these information requests may pose a significant challenge for tax directors, the task should not distract from the need to have the company’s financial data tell its tax story. This is a variation on the theme above, but it is a theme worth repeating: Not all spreadsheets are equal, and it could be a big mistake to assume that numbers will tell the same story to every audience, particularly skeptical tax examiners.

The clearest examples of potential problems are on the horizon, with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)-coordinated initiative surrounding base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) and the related BEPS Action Plan. OECD countries adopting BEPS measures will be requiring country-by-country (CbyC) reporting, disclosing certain country-specific tax data of a multinational group. The reports significantly increase the transparency of a multinational group’s tax planning to local tax authorities. A tax agency will be able to see not only the commercial performance and taxation of the group within its specific jurisdiction but also its jurisdiction’s relative share of global tax revenues. Among the objectives of the BEPS initiative are to enable tax administrators to identify and tax “stateless” income, adjust a group’s transfer prices, and otherwise ensure that multinational groups pay a “fair share” of taxes in the jurisdictions in which they operate. (By the way, some jurisdictions are adopting mandatory public disclosure of certain tax attributes for large taxpayers. Beyond the impact on a company’s multinational tax issues, consider what that visibility could affect in terms of investor and public relations as well as industry competition.)

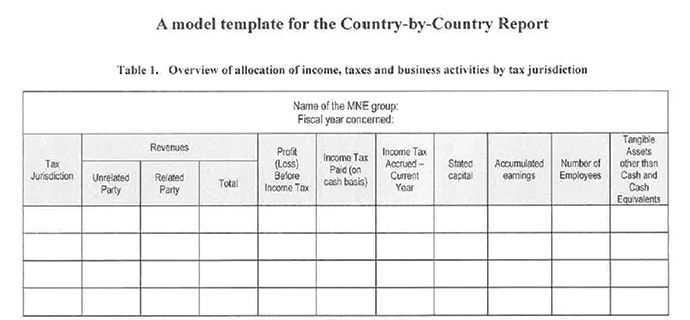

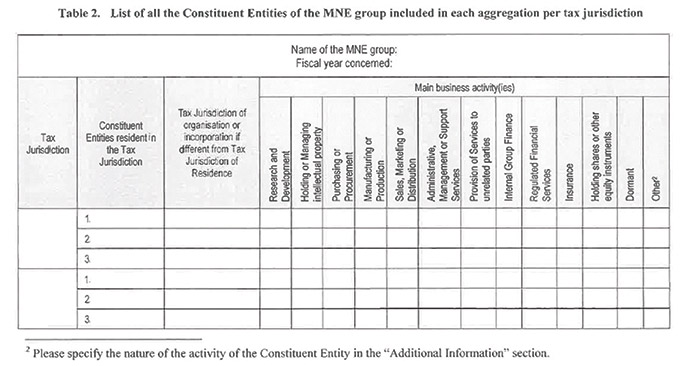

Depending on jurisdiction, these reports must be filed as early as December 31, 2017, (with respect to 2016 data) in countries that have adopted some form of BEPS legislation. Although the paradigm is to have the ultimate group parent file the CbyC report, the report will be made available to other jurisdictions where the group operates under automatic exchange of information agreements. The OECD recently issued a three-table template (see p. 26) for CbyC reports.1 The template may be adopted wholesale or modified by member countries.

Let’s imagine you are an examiner in Country X, and have received a copy of Company A’s CbyC report. What catches your eye? It isn’t very difficult to imagine that a simple profits-per-employee calculation for each jurisdiction could be one of the first things you would assess. That information is readily available in Table 1, as are the amounts of taxes paid and accrued in your jurisdiction. And if profits per employee are comparatively high but taxes are comparatively low versus other jurisdictions, it also isn’t difficult to imagine that you will want to know why.

As a tax director whose workdays aren’t getting any shorter or simpler, it is tempting to delegate the CbyC report and similar data mining and compliance exercises to others, including to technology. It is also tempting to throw data into a matrix and not consider how it may be viewed by outsiders. But consider the scenario above and how it may be worth exploring the nuances of your tax data and its presentation. Even a straightforward spreadsheet presentation could look very different through the lens of substantive tax analysis. Companies should be using the time between now and their first filing deadlines to road-test their CbyC report, both to ensure that the necessary information can be extracted from various internal systems as a practical matter (general ledger, payroll, etc.) and to assess the story it tells foreign tax authorities. In particular, once a CbyC report is filed, changes in a company’s source data will need to be disclosed on future reports, as well as the reasons for and consequences of the changes. It is worth taking time up front to determine the best available pool(s) of source data and the look and feel of different approaches to the report.

For example, who counts as an “employee”? The OECD’s model instructions for the template indicate that full-time-equivalent employees in a given jurisdiction should be reported. But the instructions are silent when it comes to addressing certain scenarios. How should an organization disclose job-sharing employees, employees on extended leaves of absence, or employees whose functions are split between multiple jurisdictions? The instructions provide that contractors may be treated as employees, but how would an organization identify and characterize those individuals as a practical matter? Should tax directors simply be looking at payroll, or are there other warehouses of information they should be mining? Have organizations even been tracking employees by legal entity, or jurisdiction, as opposed to business line or function?

“While electronic filings have moved the related activities from pencil and paper to keyboard and computer, it has not materially impacted the day-to-day activities of the corporate tax professional.” —Brad Hearn

In addition, what is the definition of an “income tax”? U.S. tax personnel understand the challenge of identifying taxes for foreign tax credit purposes. The same challenge—without the benefit of Treasury regulations and developed U.S. case law—is front and center on the CbyC report.2 Companies make all kinds of payments that are designated as “taxes” and sometimes pay taxes that are labeled otherwise in their systems. Companies also pay withholding and other taxes on income paid to and realized by other persons. Although the OECD and member countries may issue future guidance, how should an organization deal with nuances in the absence of that guidance? For example, how should a company treat taxes assumed on behalf of related and unrelated payees or other technical taxpayer issues? Should any other levies (e.g., alternative minimum and excess profits taxes) be treated as income taxes for these purposes?

From the purely practical perspective, where would an organization go for the income tax data? Presumably the U.S. and foreign income-tax accruals could be teased out of the tax provision. But is there an efficient way of getting U.S. and foreign cash taxes paid during a fiscal period? How difficult is it to tease the cash tax information out of the general ledger? Tax directors should be considering which payments should appropriately be included as “taxes” to avoid improper (and potentially unfavorable) under- or over-reporting with respect to various jurisdictions.

In addition, beyond understanding what the tax data explicitly says about their companies, tax directors should be wary of what their tax data does not say. The CbyC report focuses on the tax information of tax-paying enterprises (including taxable permanent establishments) within a given jurisdiction. It does not report on commercial activities that are not subject to tax, e.g., enterprises that claim to have no local permanent establishment so that its local revenues are not subject to local tax. Let’s say you were a foreign tax examiner and knew that a foreign company was fulfilling orders out of a local warehouse. The company had been taking the position that the warehouse activities were “preparatory and auxiliary” and therefore treaty-protected. You request a copy of the CbyC report—note, it is unclear whether such a report, prepared for disclosure to multiple governments, would have any privilege, work product, or other protection—and find that the company is paying income tax in several other jurisdictions. How long would it be before you initiated a permanent establishment audit?

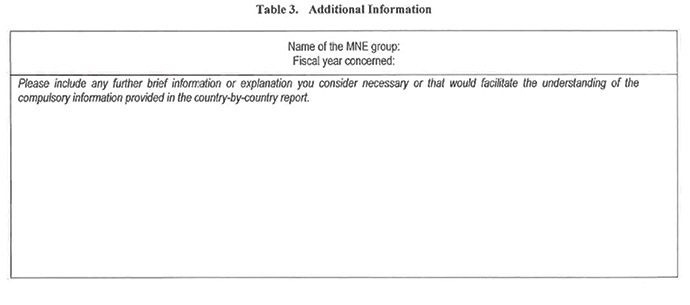

Finally, tax directors should be making the most of Table 3 and supplementing the compulsory information with explanations supporting their tax profile. This is something that should not be overlooked and cannot be delegated to tax technology. Solely based on its Table 1, and possibly even Table 2, information, a mining or natural resources company could look very similar to a company in a more mobile industry. From a multinational group perspective, both could have significant employees, capital, and assets in Country A but most of their external customers (and therefore revenues, profits, and taxes) in Country B. However, they could have very different Table 3 disclosures explaining the apparent disparities and therefore present very different risk profiles to Country A tax examiners.

“This suggests that in-house tax professionals are sensing the need to become more tech-savvy and to better understand technology trends and how available tools may help facilitate their work.” —Eli Dicker

Every multinational group should be looking with fresh eyes at the story its tax data could tell and considering how—using Table 3 to its best advantage, rationalizing its transfer pricing, rethinking its global capital structure, restructuring its supply chain or internal financing arrangements, etc.—to put its best foot forward on its CbyC report. Moreover, multinational groups should be doing this now, before the first reports are due. Once a baseline profile is established, organizations will have a tougher time making substantial changes to subsequent reports.

Don’t Spend Time or Money Building a Dinosaur

One additional dimension is important to highlight. The two scenarios discussed above reflect significantly different points in the life cycle of their underlying tax regimes. The Chapter 3 withholding and reporting rules are sufficiently longstanding that, even with periodic modifications, their overall scope and framework are relatively stable. Even the introduction of the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) rules—at least for nonfinancial companies—did not significantly change (as much as supplement) the basic approach of the rules and their application to payments and payees. Consequently, while an organization should never take a set-and-forget attitude toward tax technology, tax concepts or algorithms may be incorporated into AP systems in one major phase, with occasional tweaks to address rule developments.

In contrast, the BEPS initiative is very much a work in progress. The OECD’s BEPS Action Plan must be adopted and implemented by individual member countries. Those countries may differ on key aspects of the action plan, including the timing of local reporting requirements, identification of reporting entities, and/or the interpretation and scope of the disclosed data. Depending on a multinational group’s complexity, it may not be possible to implement a technological solution addressing BEPS in one significant transformation project. Instead, as painful as it may be in the short term, a multinational group may be best off mining data from existing processes, manually manipulating the information from the tax perspective, and delaying large technology investments until both the relevant rules and the group’s approach to those rules are more firmly established.

The Uncertain Administrative Landscape

Somewhat ironically, the drive to accelerate embedding technology in tax department processes and workflows is occurring almost contemporaneously with a slow-down in these types of efforts to upgrade and enhance system capabilities at the Internal Revenue Service. Recently, as part of IRS Commissioner John Koskinen’s prepared testimony before the Senate Finance Committee focusing on IRS budget and current operations, the commissioner observed:

- We are operating with antiquated systems that are increasingly at risk, as we continue to fall behind in upgrading both hardware infrastructure and software. Despite more than a decade of upgrades to the agency’s core business systems, we still have very old technology running alongside our more modern systems. This compromises the stability and reliability of our information systems, and leaves us open to more system failures and potential security breaches. In regard to software, we still have applications that were running when John F. Kennedy was President.

- It is important to point out that the IRS is the world’s largest financial accounting institution, and that is a tremendously risky operation to run with outdated equipment and applications. Our situation is analogous to driving a Model T automobile that has satellite radio and the latest GPS system. Even with all the bells and whistles, it is still a Model T. Our core IT systems are not sustainable without significant further investment over the next few years.3

What does this reality of shrinking budgets coupled with greater demands for taxpayer information from different sources mean for corporate tax departments? The commissioner has lamented that the IRS will “have no choice but to do less with less.” But does that mean that because the IRS will not have the resources (or the technology) to mine for data, greater productions burdens will shift to taxpayers to produce or manipulate data at the agency’s request—just because it can?

Taxpayers are obligated to comply with applicable ethical and practice rules to fully, timely, and accurately respond to information document requests.4 It is also well settled that these obligations do not extend to creating documents for taxing authorities. Yet, how should a taxpayer consider responding to a request for analysis of rather than solely production of data? It is critical that tax executives and their advisers evaluate these less apparent dimensions and implications of their technological transformations.

Similarly, greater centralization of tax data brought on by technological innovation and the development of data warehouses, databases, and the like may open the door to requests from taxing authorities for greater access to these sources. Companies should exercise caution here. The standard of relevance under the Internal Revenue Code has always been extremely broad; however, that standard should never be confused with a license to roam.

As a final note, the implications for privilege and confidentiality must be closely evaluated as tax executives consider the speed and scope of their migration to and emphasis on technological innovation. There is little or no privilege or other protection for facts and analyses performed in the ordinary course of its business. That is, is the taxpayer at risk of creating a bad paper trail for itself?

The above scenarios represent the tip of the iceberg in terms of illustrating the indisputable value of tax technology. They also demonstrate the risks of undue reliance on technology solutions that may not appropriately address a multinational group’s immediate tax needs and that may provide incomplete or superficial considerations of the broader implications of technological innovation in the tax department. Before embracing and adopting any tax technology solution, tax directors should understand its limitations in terms of translating commercial terms into tax concepts, glossing over nuances that may affect a company’s perceived tax profile, and ability to incorporate evolving tax requirements. Most of all, tax directors should view tax technology as enabling, but not replacing, substantive tax analysis. Technological innovation in the tax department is here to stay; proper calibration to a department’s specific needs represents the continuing challenge for the tax executive.

Michael Levin-Epstein is senior editor of Tax Executive.

Editor’s Note

The foregoing discussion draws on and expands two recent panel discussions that explored tax technology and the global environment: “Tax Technology and the Global Environment” at TEI’s 2015 Midyear Conference in Washington, D.C., and the American Bar Association’s Tax Executive Workshop, “Using Tax Technology for Multiple Tax Types in a Global Environment,” in Munich, Germany. The opinions expressed are those of the participants and do not necessarily reflect the views of the firms with which they are associated.

Endnotes

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2014), Guidance on Transfer Pricing Documentation and Country-by-Country Reporting, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, OECD Publishing, Annex III to Chapter V. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264219236-en.

- As defined by the OECD, the term “taxes” means compulsory, “unrequited” payments to general government. Taxes are unrequited in the sense that benefits provided by a government to taxpayers are not normally in proportion to their payments. OECD (2015), Taxing Wages 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/tax_wages-2015-en.

- Testimony, John A. Koskinen, Commissioner, Internal Revenue Service, before the Senate Finance Committee, Feb. 3, 2015, on IRS Budget and Correct Operations.

- Circular 230; (Rev. 6-2014); Rules Governing Practice Before the Internal Revenue Service.