For contentious U.S. federal tax issues, tax controversy management tends to follow a horizontal path from examination to appeals and finally litigation. The likelihood of being embroiled in a contentious issue increased recently as the Internal Revenue Service’s Large Business & International (LB&I) Division announced another round of campaigns. Campaign may suggest the IRS is taking a combative approach, but if budget constraints continue, the IRS may be more receptive to taxpayers and practitioners using provisions in the Internal Revenue Manual (IRM) as an opening to a more collaborative approach to resolving tax controversy matters.

For contentious U.S. federal tax issues, tax controversy management tends to follow a horizontal path from examination to appeals and finally litigation. The likelihood of being embroiled in a contentious issue increased recently as the Internal Revenue Service’s Large Business & International (LB&I) Division announced another round of campaigns. Campaign may suggest the IRS is taking a combative approach, but if budget constraints continue, the IRS may be more receptive to taxpayers and practitioners using provisions in the Internal Revenue Manual (IRM) as an opening to a more collaborative approach to resolving tax controversy matters.

How can tax executives use their knowledge of the organizational structure of LB&I and the IRM to efficiently and effectively manage U.S. federal tax controversy?

Answer: Now more than ever, taxpayers and in-house professionals need to understand the quasi-matrix organizational structure of the LB&I division. In a previous issue of Tax Executive magazine the authors discussed the reorganization of LB&I, asking, “What happened to transparency and collaboration?” They suggested that LB&I was becoming more militaristic by launching campaigns.1 Even if campaign is typically used in military jargon, the IRM hints at a conciliatory approach to examinations. To better understand the principles of collaboration that are detailed in IRM 4.46.1.4, tax executives should become familiar with the organizational structure of LB&I, as this familiarity can be used to manage tax controversy efficiently and effectively at the examination level.

LB&I’s Organizational Structure

On February 25, 2016, LB&I released Publication 5125, titled the Large Business & International Examination Process (LEP). The LEP sets forth an organizational approach for conducting professional examinations and replaces Publication 4837, Achieving Quality Examinations Through Effective Planning, Execution, and Resolution (or QEP), which mentioned LB&I’s Rules of Engagement. Publication 5125 no longer mentions such rules, instead persistently using the terms collaborate and collaborative manner. With such terms in mind, tax executives should reacquaint themselves with IRM 4.46.1.4 (Principles of Collaboration) and IRM 4.46.1.4.3 (Elevating Issue Concerns) and consider the organizational structure of LB&I if they seek to successfully manage U.S. federal tax controversies at the examination level.

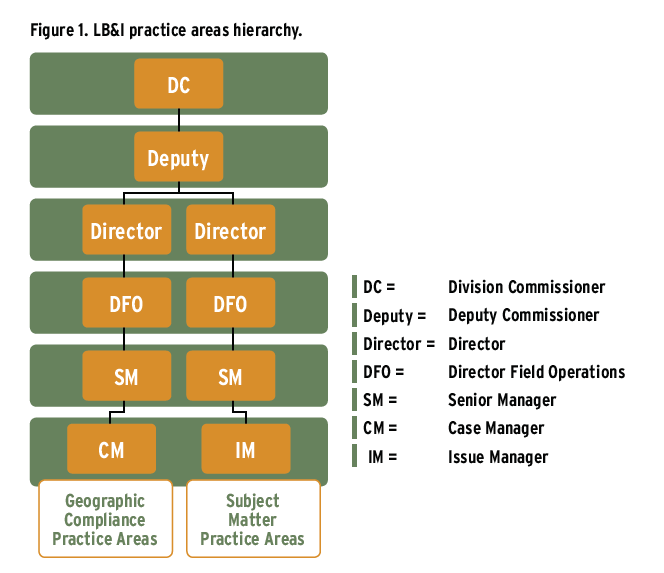

The graphic design of LB&I’s current organizational chart2 does not readily expose the dichotomous nature of the organization’s structure. But a closer inspection of LB&I’s organizational structure reveals two distinctly different types of practice areas, which appear below in Figure 1. The Geographic Compliance Practice Areas (GCPAs) and the Subject Matter Practice Areas (SMPAs) are rendered in greater detail in a Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA) report published on September 14, 2016.3 Although Figure 1 does not detail each of the GCPAs and SMPAs as presented in the TIGTA report, it is sufficient to facilitate the discussion of the collaboration and elevation that is stipulated in the IRM and to suggest how the organizational structure should be navigated.

Navigating a Quasi-Matrix Structure

While the LB&I organization is built along two dimensions (i.e., GCPAs and SMPAs) as anticipated by those contemplating matrix organizations,4 the dual-boss aspect expected in such structures is not as pronounced. For this reason, I’m proposing that LB&I has a quasi-matrix organizational structure. As Figure 1 shows, examination personnel in both the GCPA and SMPA respectively have separate and distinct hierarchal management structures that converge at the deputy level. For the tax executive, the most immediate benefit of knowing this information is best illustrated by way of an example.

Imagine a scenario in which taxpayer A is being examined by the Northeastern GCPA and an adjustment is being proposed with respect to a domestic tax credit issue. The tax executive for taxpayer A has been made aware of the fact that taxpayer B was examined by the Western GPCA for the same exact issue with similar facts. However, the IRS proposed no changes to taxpayer B’s return. This disparate treatment of tax issues and taxpayers is an ideal situation for collaboration and elevation as anticipated by IRM 4.46.1.4 and 4.46.1.4.3, respectively. This is particularly true in the above hypothetical scenario, because the principles of collaboration were designed among other things to promote consistent treatment between similarly situated taxpayers or cases.

Collaboration and Elevation

For situations like the inconsistent tax treatment scenario mentioned above, the IRM suggests that collaboration should begin with the issue manager and the case manager as appropriate before elevating the relevant issue to senior management and executives. It is important to note that in addition to promoting consistent tax treatment, the principles of collaboration were designed to do the following:

- clarify individual roles, responsibilities, and lines of authority to help ensure end-to-end accountability and provide clear procedural guidance for elevating concerns;

- facilitate getting to the right answer for a particular issue or case;

- encourage engagement with subject matter experts in the relevant practice area(s) and counsel; and

- reinforce the importance of transparency.

Since the IRM is written like a recipe, the success anticipated by the principles of collaboration requires a bit of finesse and understanding of the people involved at each elevation level. Unfortunately, this makes the principles of collaboration and elevation more an art than a science.

Final Considerations

The inconsistent treatment scenario discussed above is not the only scenario in which the principles of collaboration and elevation might be appropriately considered and pursued. Although the campaign process as intended should help illuminate the areas where collaboration among LB&I managers and executives would prevent the IRS from treating taxpayers inconsistently, this process may not always function as designed. Moreover, issues raised by exam teams will not always originate from a campaign and furthermore, a taxpayer on the West Coast does not always have the benefit of knowing what tax treatment a taxpayer is getting on the East Coast. Therefore it is critical for a tax executive to promptly elevate and collaborate when encountering an agent who is clearly taking an incorrect position to the point where the issue is unlikely to be resolved at the examination level. More important, a tax executive who continues to be at odds with IRS management or executives during the elevation process should make sure the SMPA with ultimate responsibility for the area of the tax law being considered is made aware of the position the IRS is taking on the issue. Such actions may preclude the need to enter costly and unnecessary litigation.

Rosemary Sereti is a managing director with Deloitte Tax LLP’s Washington National Tax and Tax Controversy Services practice groups. She formerly served as the deputy commissioner for the Large Business and International (LB&I) Division at the Internal Revenue Service.

Endnotes

- “The New LB&I: Recent IRS Reorganization Raises Panoply of Significant Issues,” Tax Executives Institute, February 23, 2016, http://taxexecutive.org/the-new-lbi/.

- “LB&I Organizational Chart,” Internal Revenue Service, last updated November 2017, www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/lbiorgchart.pdf.

- “The Large Business and International Division’s Strategic Shift to Issue-Focused Examinations Would Benefit From Reliable Information on Compliance Results,” Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration (TIGTA), September 14, 2016, www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2016reports/201630089fr.pdf.

- Jay R. Galbraith, Designing Complex Organizations (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1973).