Managing state tax controversies is a complex task that involves an understanding of substantive and procedural rules that vary significantly by jurisdiction. Part I of this article, published in the May/June issue of Tax Executive, explored considerations for selecting the best forum for litigation. Part II of this article addresses the factors that taxpayers should consider when coordinating multistate litigation. Specifically, we focus on prioritizing litigation among multiple states, the implications of state information-sharing, and protecting evidentiary privileges.

Prioritizing Multistate Litigation

Although many state tax disputes center on a state’s unique statute or interpretation of law, many state tax issues will be questioned by more than one state. Developing a multistate strategy to coordinate such litigation is essential to resolving such issues efficiently.

Moreover, developing a comprehensive position for such issues is critical because many state tax issues have multistate consequences. For example, nonbusiness, apportionment, and nexus positions challenged by one state are likely to be challenged by others. Although the ultimate position taken may vary based on an individual state’s authorities, the reasoning behind such positions should be thoughtful and thorough.

The ability to articulate such decisions to a judge is essential to maintain credibility. Inconsistencies do not go unnoticed. For example, in Matter of British Land (Md.) Inc. v. Tax Appeals Tribunal,1 the New York appellate division emphasized a taxpayer’s inconsistent unitary filing positions. The taxpayer asserted that its Maryland operation was not unitary with its New York operation for New York franchise tax purposes. In dismissing the taxpayer’s argument and holding that the taxpayer’s Maryland operation was unitary with its New York operation, the court noted that, for Maryland tax purposes, the taxpayer had treated its Maryland operation as unitary with its New York operation. Similarly, taxpayers should ensure that positions they take in a particular state are consistent from year to year.

Had the taxpayer in New Cingular not taken this step, its previously protected customer information could have been available to the public or to other state tax authorities simply because the case had progressed to a new stage of litigation.

In determining how best to prioritize litigation matters in one jurisdiction over another, taxpayers should consider the impact of existing case precedent and law. While a state’s audit progress or backlog of cases may dictate which case goes first, the time and speed in which a forum may resolve matters and the availability of alternative forums (as discussed in detail in Part I) is an important consideration. Where a taxpayer has the opportunity to fast-track (or slow down) litigation, taxpayers should seek to advance litigation in favorable or influential states first. Thus, a taxpayer may choose to expedite a case in a state that has well-developed authority or in a forum that has a reputation for fairness.

Similarly, a taxpayer may seek to expedite litigation in a state where the amount at issue is significant. Other states will be less likely to litigate an issue that the taxpayer has won following a robust trial, often enabling such litigation to be dismissed or settled.

Information Sharing

When coordinating multistate litigation, taxpayers also should consider the implications of sharing nonprivileged information, as states are increasingly sharing information with each other.

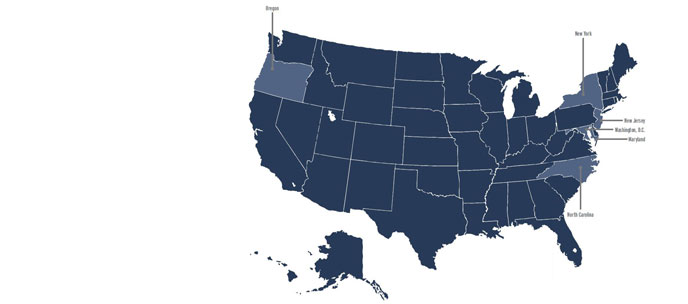

In 1993, the Federation of Tax Administrators (FTA) facilitated the execution of the Uniform Exchange of Information Agreement between forty-eight states, the District of Columbia, New York City, and the Multistate Tax Commission (MTC). The agreement promotes information exchanges among the signatories that are specifically requested or voluntarily transmitted under its exchange procedures. Similarly, the Internal Revenue Service has executed a memorandum of understanding with state tax agencies and the MTC to share tax returns and return information as authorized under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) § 6103(d). Many states, such as New York and North Carolina, have also adopted statutory provisions akin to IRC § 6103(d) providing an exception to general confidentiality rules.2 Such statutes generally permit disclosure of corporate tax information to certain authorized federal and state authorities if there is reciprocity with disclosure.

Taxpayers should anticipate that their confidential information may be disseminated through these information-sharing agreements, and they should seek a protective order where appropriate. For example, in Harley-Davidson Inc. v. Oregon Department of Revenue,3 the taxpayer requested a protective order for business records requested in discovery for an Oregon corporate excise tax dispute. The taxpayer did not want its business records containing trade secrets and employee and customer information to become a part of the public record. Oregon took the position that it would not publicly disclose the records but implied that it would share the business records with other state tax authorities and the MTC under its information-sharing arrangements. The Oregon Tax Court ultimately denied the taxpayer’s motion, finding that the records request would not cause annoyance, embarrassment, or oppression. However, the case demonstrates that taxpayers should take a proactive approach to protect information that must be disclosed in discovery, because such information may be more widely dispersed.

In addition to protecting the taxpayer’s information, taxpayers should also take due care to protect their customers’ information throughout the litigation process. In New Cingular Wireless PCS, LLC v. Dir., Div. of Taxation,4 the taxpayer submitted customer information in support of its New Jersey sales tax refund. The taxpayer sought a protective order to exclude its customer information from public inspection. Such information was entitled to confidentiality during the administrative appeals process; however, confidentiality had to be reevaluated under the tax court’s rules.5 The New Jersey Tax Court held that the customer information was exempt from disclosure to the public and required procedures to ensure that the information would not be disclosed. Had the taxpayer in New Cingular not taken this step, its previously protected customer information could have been available to the public or to other state tax authorities simply because the case had progressed to a new stage of litigation.

Preserving Evidentiary Privileges

Taxpayers litigating in multiple states also should be aware that the rules governing the attorney–client privilege, work product doctrine, and accountant–client privilege vary by state and that the disclosure of evidence in one state may result in the waiver of such protection in other states. An in-depth discussion regarding the scope of such protections is beyond the scope of this article and has been covered elsewhere.6

That said, state attorney–client and accountant–client privileges generally are waived if information has been disclosed to third persons without the need to know such information, and work product protections are generally waived if information is disclosed to an adversary or conduit to an adversary. Thus, disclosure of information to one state will result in the loss of protection in subsequent litigation matters. Taxpayers should thus consider the impact the information will have on all litigation matters when choosing to share such information.

Strategical Solutions

State tax litigation is challenging not only because of the complexities a particular case presents but also because of the multidimensional challenges presented by litigating similar cases in multiple forums. Focusing on a comprehensive strategy for all related litigation matters early in the state controversy life cycle will have a meaningful impact on the final outcome.

Jeffrey A. Friedman is a partner and Stephanie Do is an associate in the law firm of Sutherland, Asbill & Brennan, LLP, in Washington, D.C. Pilar Mata is state tax counsel at TEI.

Endnotes

- Matter of British Land (Md.) Inc. v. Tax Appeals Tribunal, 202 A.D.2d 867 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 3d Dep’t 1994), rev’d on other grounds, 85 N.Y.2d 139 (N.Y. 1995).

- See N.Y. Tax Law § 202(3); N.C. Gen. Stat. § 105-259(b)(3).

- Harley-Davidson Inc. v. Ore. Dep’t of Revenue, TC-MD 040897A (Or. Tax 2006).

- New Cingular Wireless PCS, LLC v. Dir., Div. of Taxation, 000003-2012 (N.J. Tax 2012).

- Though the information was protected from public access during the administrative appeals process, the New Jersey Division of Taxation may have been able to disclose such information to certain authorized federal and state tax authorities under its information-sharing provision. N.J. Rev. Stat. §§ 54:50-8(a), 54:50-9(f).

- See P. Mata and R. Call, Best Practices for Creating, Maintaining, and Protecting State Income Tax Audit Files, Tax Executive (Jan./Feb. 2010), for a general discussion of the attorney–client privilege and work-product issues. See P. Mata and M. Smith, Demystifying Accountant-Client Privileges in State Tax Litigation, State Tax Notes (Apr. 2, 2012) for a discussion of state accountant–client privileges.