Managing state and local tax controversies is not an easy task. In addition to understanding the differences between the substantive laws applied in each jurisdiction, multistate taxpayers also need to understand the differences in procedural rules governing those disputes. In this two-part article, we address the most common issues that impact how taxpayers litigate state tax cases.

Part I addresses the consequences arising from one of the most critical decisions that taxpayers face when engaging in a state tax controversy: determining the best forum for filing a lawsuit. Not all states offer alternative forums for taxpayers to challenge assessments. For instance, Maryland requires many taxpayers to bring suit at the Maryland Tax Court. However, in states that do provide alternative forums, taxpayers are required to decide not only whether to challenge an assessment but which forum is most appropriate for bringing that challenge. This decision will be influenced by a number of factors, including the nature of the process, whether taxpayers must “pay to play,” whether taxpayers will lose confidentiality rights, the type of evidentiary rules that will be applied, at which point the record will be set, the scope of the parties’ appeal rights, and the time spent in litigation.

Part II, which will appear in TEI’s July/August issue, addresses factors that taxpayers should consider when coordinating multistate tax litigation. Such issues include prioritizing litigation among multiple states, protecting the evidentiary privileges, and the implications of state information sharing.

Nature of the Adjudicative Process

As state and local taxpayers are well aware, the nature of the process offered to taxpayers at the administrative level varies widely from state to state. At best, administrative tribunals are staffed by independent judges who have knowledge of the tax laws before them, are governed by clear rules of evidence, and issue precedential opinions. At worst, those administrative tribunals are nothing more than rubber stamps for a state’s department of revenue. In such jurisdictions, taxpayers may opt to shortcut or bypass a state’s administrative hearing process altogether by paying the tax and filing a refund claim that can be appealed to a state court.

California’s administrative process provides an interesting example. Corporate income taxpayers1 who have received a notice of proposed assessment and wish to avail themselves of California’s administrative process must file a written protest, which is then assigned to a protest hearing officer within the California Franchise Tax Board (FTB), the same agency that issued the assessment.2 Following an informal protest hearing and potentially years of responding to requests for information and documentation, the protest hearing of ficer reviews the proposed decision with the FTB’s management, which may accept or reverse the protest hearing officer’s decision. The protest hearing officer will then issue a final determination letter to the taxpayer, and the FTB will issue a notice of assessment.

The taxpayer then has the opportunity to appeal the protest hearing officer’s decision to the California Board of Equalization (BOE),3 a five-member board composed of the state’s controller and four elected members. The appeals process offered by the BOE bears no resemblance to any other state’s. First, parties in standard appeals are offered only fifteen minutes at the BOE hearing to present their case. Therefore, taxpayers with complex matters must often meet with BOE members beforehand to educate them about their case. Second, the representative appointed by the FTB to defend the FTB’s assessment may be the very same individual who served as the protest hearing officer in the taxpayer’s case. Adding insult to injury, the FTB may use that same individual as the protest hearing officer in subsequent audit cycles involving that same taxpayer. It is challenging for the same individual to fill the role of an impartial hearing officer after advocating directly against the taxpayer in BOE proceedings.

California taxpayers are entitled to receive a written opinion in cases where the amount in dispute is $500,000 or more.4 Such opinions must include findings of fact, a summary of the legal issues presented, an analysis of the BOE’s decision, and the disposition of the case.5 This benefit is a result of legislation passed in 2012 mandating that such opinions be issued.6 Proponents of that legislation noted that although BOE had issued 1,615 formal opinions during the 1980s, the number issued between 2000 and 2010 had dropped precipitously to 32.7 Another significant benefit of the BOE hearing process is that a successful taxpayer need not worry about appeals. The FTB is prevented from appealing an unfavorable BOE decision.8

If the BOE denies the taxpayer’s appeal, the taxpayer must then pay the tax and file an appeal in superior court.9 It is only at this time that the taxpayer’s case will be heard by an independent and impartial judge.

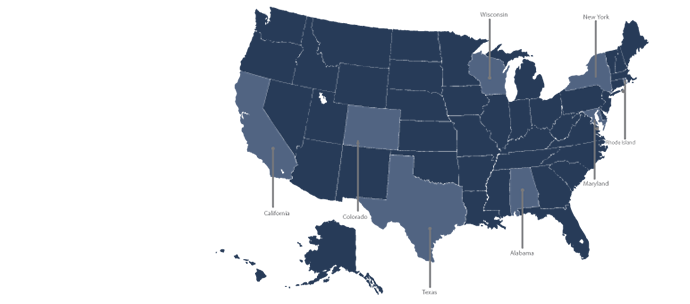

Though California’s adjudicative process is unusual, approximately fifteen states lack a tax court or independent tribunal.10 In those states, like California, the tribunal is located within or reports to the state’s department of revenue or a subordinate executive agency. The perception that such administrative forums can, at times, produce unfair decisions has led to legislation requiring the establishment of independent tax tribunals or requiring additional transparency. For example, in 2013, Pennsylvania enacted H.B. 465, adopting reforms to provide independence in tax appeals heard by the Board of Finance and Revenue.

Approximately thirty-five states and the District of Columbia provide independent tax tribunals either within the executive branch or within the state court whose jurisdiction is limited to tax cases.11 For example, in 2014, Alabama enacted H.B. 105, which established the independent Alabama Tax Tribunal under the executive branch. Alabama’s legislation was modeled after the American Bar Association’s Model State Administrative Tax Tribunal Act (Model Act).12 Key features of the Model Act include of fering a fair and independent prepayment procedure and staf fing the court with appointed judges who have substantial knowledge of tax law and published decisions.

Pay to Play

States generally permit the taxpayer to dispute his assessment before an administrative hearing of ficer or the tax commissioner prior to paying their assessment. However, many states do not grant the taxpayer access to independent and impartial tribunals until after he has paid the assessed tax and filed an administrative refund claim. Thus, another factor to consider when choosing a forum in state tax controversies is whether the taxpayer must pay the tax (as well as interest and penalties) before entering that forum, commonly referred to as the pay-to-play requirement.

States such as Colorado and Texas provide taxpayers the option to either pay the assessment or post a bond before proceeding in district court. While doing so avoids the obvious hardship of paying the tax up front, it nonetheless imposes an additional cost upon the taxpayer without the benefit of curtailing interest on the assessment. The taxpayer in Richmont Aviation Inc. v. Combs13 challenged Texas’s law, which requires a bond in an amount double the assessment, unless the taxpayer can demonstrate indigence.14 The Texas Court of Appeals held that Texas’ statutory pay-to-play requirement violated the state’s constitutional provisions on open access to courts.

Finally, exorbitant interest rates on assessments may counsel toward paying the assessment and advancing the process, if for no other reason than to stem that cost. For example, the District of Columbia charges ten percent on assessments (and pays two percent on refunds),15 whereas Rhode Island and Wisconsin charge eighteen percent on assessments (and pay 3.25 percent and 3 percent on refunds, respectively).16 Taxpayers litigating in these forums thus have a significant incentive to pay the tax shortly after receiving an assessment.

Taxpayer Confidentiality Rights

Whether a forum protects the confidentiality of taxpayer’s information is another factor to consider when evaluating state tax litigation. In many administrative forums, tax returns, records, and briefings remain confidential throughout the adjudicative process. However, moving into another proceeding or forum may result in an inadvertent waiver of confidentiality rights.

For example, protest proceedings with the California FTB are confidential.17 However, appealing the FTB’s determination to the BOE constitutes a waiver of the taxpayer’s right to confidentiality for all information provided to the BOE—regardless of whether advanced by the taxpayer or the FTB.18

These rules are particularly problematic, because the BOE does not of fer taxpayers the right to protect these records through a protective order, as they are able to do in court. And once the records are “released” to the public in the BOE proceedings, they are no longer considered confidential and cannot be protected by a protective order in superior court.

Evidentiary Rules

Another factor that may influence a taxpayer’s decision to choose a particular forum in state tax cases is the applicable evidentiary rules. Many states provide relaxed rules of evidence (or no rules at all) in administrative forums. Although this provides taxpayers with some latitude to introduce evidence that may not be admissible in court and arguably reduces the expense of litigation by eliminating procedural battles regarding the admissibility of evidence, states may also use this opportunity to their advantage. For example, auditors often base their assessments on information obtained from newspaper articles and websites such as Wikipedia. Such evidence may be cited to in some administrative forums even though it would be considered hearsay and excluded if presented in a court of law. Moving directly to a forum that eliminates such distractions from the record may benefit taxpayers where inadmissible evidence is unfavorable or contradicts the testimony provided by the taxpayer’s own witnesses and documents.

Setting the Record

A taxpayer’s choice of forum also may be affected by the forum in which the record will be set. Many states provide the parties with the right to trial de novo once in state court, even if the parties have undergone an administrative hearing or trial. Offering a trial de novo at a later stage in the process may benefit both parties by allowing them to test witnesses and refine arguments and theories in a forum that is not conclusive and which is generally subject to more relaxed evidentiary rules. It also provides the parties with an opportunity to eliminate or settle smaller issues factoring into the assessment, such as factual or calculation issues.19 However, taking a case to litigation twice will increase the taxpayer’s overall litigation costs and almost invariably provides the parties with additional discovery, whether it be formal or informal.

Right To Appeal

Another factor that may af fect a taxpayer’s choice of forum is the parties’ right to appeal. As mentioned above, California, for example, permits taxpayers to appeal an adverse decision arising from an appeal to the BOE, but the state precludes the FTB from appealing an issue decided against it at the BOE.20 Similarly, decisions of the Tax Appeals Tribunal in New York are final and binding with respect to the Division of Taxation and may only be appealed by the taxpayer.21 The chance to curtail years of litigation with a win before such administrative tribunals is significant; even a partial win will simplify the taxpayer’s case in later proceedings.

Time To Litigate

Finally, a taxpayer’s choice of forum should take into account the amount of time it will take to litigate and possibly appeal an adverse decision. Taxpayers often pursue optional administrative processes because they provide an opportunity to resolve factual disputes and calculation issues without the expense of a full evidentiary trial. However, where a case involves novel or common legal questions that are likely to be appealed, the time added by optional administrative appeals processes will not benefit the taxpayer.

Perhaps the most obvious impact is on the cost of the overall litigation. Even if done ef ficiently, an additional administrative process will increase the cost of the total litigation. However, cost is not the only factor. Extending the litigation life cycle can also be problematic if the issue is current and recurring, for the taxpayer, if the taxpayer will have more dif ficulty retrieving evidence, or if the taxpayer’s witnesses are less likely to be available as time goes on. Given that it often takes years to work through the administrative process, time is yet another factor that will impact the decision of to which forum a case should be brought.

Forum Futures

Although some states only provide taxpayers with one avenue to litigate state tax controversies, most states provide alternative paths. The implications arising from this decision can be significant. Taxpayers should thus use care in selecting their forum to litigate.

Jeffrey A. Friedman is a partner and Stephanie Do is an associate in the law firm of Sutherland, Asbill & Brennan LLP in Washington, D.C. Pilar Mata is state tax counsel at TEI.

- The FTB administers the corporate and personal income taxes. Other state taxes and fees, such as sales and use taxes, are administered and assessed by the California Board of Equalization (BOE). The BOE representatives also handle the protest process for such taxes. Following a decision on the protest, an appeal may similarly be filed with the BOE’s five-member board

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Cd. §§ 19041-19045

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Cd. §§ 19045-19048

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Cd. § 40(a)(1.

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Cd. § 40(b)

- Cal. AB 2323, Stats. 2012, c. 788, §1 (eff. Jan 1, 2013)

- Cal. Senate Governance and Finance Committee, Bill Analysis for AB 2323 (2012)

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Cd. § 19347

- Id.

- AICPA, Chart of States With and Without State Tax Tribunals (Feb. 2, 2015); Douglas L. Lindholm et al.,The Best and Worst State Tax Administration: COST Scorecard on Tax Appeals & Procedural Requirements (Dec. 2013), Council On State Taxation

- Id.

- American Bar Association, Model State Administrative Tax Tribunal Act (Aug. 2006)

- Richmont Aviation Inc. v. Combs, No. 03-11-00486-CV, 2013 WL 5272834 (Tex. App. – Austin 2013), petition denied, No. 13-0857 (Tex. 2014)

- Tex. Tax Cd. Ann. §§ 112.051, 112.108

- D.C. Code Ann. §§ 47-4201(d), 47-4202(c)

- R.I. Gen Laws §§ 44-1-7, 44-1-7.1; Wisc. Stat. §§ 71.82(2)(a), 71.82(1)(b)

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Cd. §§ 19542, 19552

- California amended its confidentiality regulatory provision in 2014, adopting changes that further emphasize the broad waiver of confidentiality associated with filing an appeal to the BOE. Cal. Rev. & Tax. Cd. § 19545; 18 Cal. Code Reg. § 5573(a)

- Taxpayers should exercise care, however, to introduce their arguments at all levels of administrative proceedings even if they are entitled to a trial de novo. Taxpayers failing to introduce such evidence may be deemed to have exhausted their administrative remedies if they omit critical arguments or facts from early proceedings and filings. This exercise is particularly complicated where the taxpayer may have alternative theories of recovery

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Cd. § 19347

- N.Y. Tax Law § 2016