U.S. tax reform became a reality on December 22, 2017, when President Donald Trump signed the 2017 tax reform reconciliation act (the Act) into law. The Act represents a fundamental and dramatic shift in U.S. corporate taxation, particularly concerning the taxation of foreign earnings. Since late December, companies have focused intensely on understanding the inherent complexities within the Act and gathering the necessary data to determine their impact. Assessing the financial reporting implications of tax reform has been and continues to be a priority for many organizations.

With limited exceptions, the U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) require recognizing the current and future (or deferred) tax consequences of all events that have been reported in financial statements. When tax law changes, relevant accounting guidance requires any impact on how current and deferred taxes are recognized and measured to be accounted for during the period in which the law is enacted, regardless of its effective date. As a result, accounting for the effects of a change in law is often required well before such effects are reflected in tax returns. In many instances, the need to understand the impact of a change in tax law in a very compressed period and to account promptly for the effects results in added complexity.

The combination of the comprehensive nature of the Act, the speed at which Congress worked to pass it, and the proximity of its enactment date to the end of the 2017 calendar year created significant challenges for many companies trying to close their books. Although tax reform was top-of-mind for most of 2017, draft legislation did not emerge until November, which made preparing for tax reform difficult. As a result, many tax professionals were confronted with analyzing hundreds of pages of the most significant tax law change in three decades, often without needed guidance from Treasury or the Internal Revenue Service. To add to the complexity, as the law was analyzed in greater detail, numerous questions emerged about how it should apply in particular circumstances. Although the issuance of Treasury and IRS guidance has provided some clarity, many of these developments came late in the reporting period. Furthermore, many soon discovered that certain aspects of the Act required voluminous data, much of which companies did not routinely maintain. The best example is the significant historical information (including all post-1986 undistributed foreign earnings and profits and tax pools) required to calculate tax liability resulting from the mandatory deemed repatriation of foreign earnings (the toll tax). All this has been required at a time when most organizations are already resource-constrained and have little capacity to handle additional work.

Under U.S. GAAP, companies must account for tax laws as enacted and therefore cannot consider any anticipated changes in tax law or expected future interpretations.

Importantly, most of the complex changes upon which the business community’s attention has centered since tax reform was enacted—for example, the tax on global intangible low-taxed income, or GILTI, the base erosion and anti-abuse tax, or BEAT, and the deduction for foreign-derived intangible income, or FDII—impact financial reporting only on a prospective basis, starting in 2018. However, several provisions of the Act immediately affected financial statements and thus needed to be recorded in the enactment period. Remeasuring deferred tax assets and liabilities to reflect the decrease in the corporate tax rate to twenty-one percent, estimating the toll tax liability, and assessing the impact of several other rule changes on deferred taxes, such as the repeal of the corporate alternative minimum tax (AMT), changes associated with the executive compensation deduction, the full-expensing provisions, and the impact of the various international provisions on outside basis differences are all examples of provisions that had to be considered in the 2017 financial statements. In addition to accounting for the specific provisions of the Act, companies also had to determine whether tax law changes led to any changes to judgments associated with valuation allowances, uncertain tax positions, or indefinite reinvestment assertions.

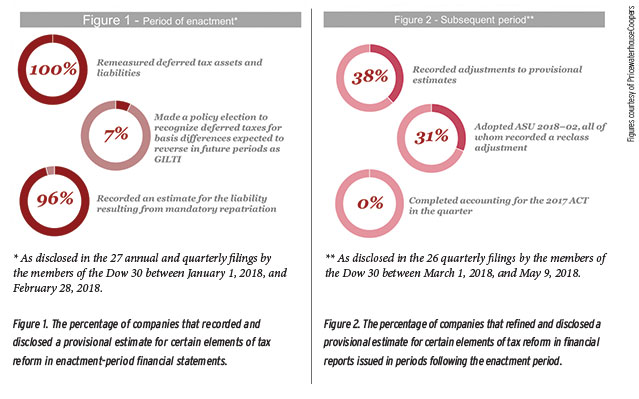

Anticipating the challenges companies would face, the Securities and Exchange Commission quickly issued guidance in Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 118 (SAB 118), which addresses circumstances where the accounting for certain aspects of the Act, during the enactment period, is not complete. The guidance allowed for an extension of the time to complete the accounting for tax reform (referred to as a measurement period) not to exceed one year from the date of enactment. When a company does not have the necessary information available, prepared, or analyzed (including computations) in sufficient detail to complete the accounting, SAB 118 permits the use of provisional amounts to the extent that a reasonable estimate can be made. If a company does not believe it can make a reasonable estimate, SAB 118 requires the old tax law to be followed. In either instance, SAB 118 requires certain disclosures essentially describing what computations are considered provisional, why the accounting is incomplete, and details regarding what additional information must be obtained, prepared, or analyzed before the estimate can be finalized.

Complexities in the tax law aside, many companies may have initially believed that the accounting for some provisions of the Act would be fairly straightforward to reflect in their financial statements and therefore could be completed during the enactment period. However, as the reporting period progressed, it became apparent that even ostensibly clear-cut provisions may be challenging to account for. For example, while many may have initially thought that accounting for the reduced tax rate would not be complicated, even this was not without challenges. To reflect the effect of the rate change in their financial statements, non-calendar-year-end companies were tasked with performing a potentially cumbersome scheduling exercise to identify existing deferred taxes that would reverse at a blended tax rate in the current year and those that would reverse in the future at the new twenty-one-percent tax rate. The reduced rate and creation of a new foreign tax credit (FTC) limitation for branch activity may have also required changes to the accounting for a company’s branch operations. It is possible, for example, that foreign taxes paid by the branch were no longer expected to be fully creditable. Despite even the best of intentions, as the reporting period progressed and companies worked through the assessment of the financial reporting effects, it became apparent just how challenging it would be to complete the accounting in the enactment period.

A review of public company disclosures covering the enactment period reveals that the vast majority of corporations applied the guidance in SAB 118 to nearly all financial statement aspects of tax reform. That trend continued in the first quarter of 2018, as very few companies finalized provisional amounts and continued to apply SAB 118 as they worked to complete the accounting related to tax reform within the measurement period.

Refining Provisional Estimates

The question many now face is when to finalize or refine provisional estimates. The SEC requires in SAB 118 that companies make a “good faith effort” to complete their accounting as soon as possible during the one-year measurement period. In addition, estimates should be updated each quarter within the measurement period as additional information becomes available (including further guidance or interpretations from Treasury, the IRS, or others that relate to items that were accounted for provisionally under SAB 118) or as the analysis is otherwise refined. In other words, companies should not wait until the end of the measurement period to update provisional estimates, particularly if they are aware that estimates have materially changed. Although only limited refinements to provisional estimates were made in the first quarter, the pressure (both internal and external) to complete the accounting for the enactment period will keep building in subsequent periods.

In evaluating when to consider provisional estimates complete, companies have questioned if the filing of the tax return should factor into the determination. In fact, in certain instances companies have suggested that the accounting cannot be complete until the company’s tax return is finished. This perspective may be driven by the fact that many companies have now shifted their attention to the tax return. Alternatively, this may be assumed true simply because the extended due date for filing calendar-year-end corporate tax returns generally falls within the measurement period provided in SAB 118. Irrespective of the reasoning, it is important to remember that although SAB 118 extends the time to complete enactment-period accounting estimates, it does not allow a company to defer recording adjustments to estimates as they are known. In addition, it is not expected that companies would hold open the accounting for items for which there is no additional work to be completed.

Another issue that can affect the decision about when to refine provisional estimates is whether the accounting for tax reform should be considered in the aggregate. Given the many changes the Act has brought about, multiple issues resulted in provisional estimates that raise the potential for various impacts of the change in tax law being disclosed as finalized in different periods. The SEC clarified in SAB 118 that there may be circumstances where certain aspects of tax reform are finalized whereas others remain provisional. This confusion may prevent a company from finalizing provisional estimates within a single period. In other words, holding completed items open as provisional solely because there are other items where the accounting is not yet complete seems inconsistent with the guidance SAB 118 provides.

The expectation that the IRS and Treasury may issue further guidance during the measurement period has raised a similar question with respect to when provisional estimates should be considered “final.” Guidance issued thus far has undoubtedly been helpful, as it has answered certain questions resulting from the Act that caused potentially significant variations in accounting estimates related to tax reform. The general framework under ASC 740 requires the impact of future developments to be recorded in the period during which guidance is issued. This means new guidance from the IRS and Treasury might necessitate subsequent revisions of period-of-enactment accounting even after a company has disclosed that the provisional amounts accounted for under SAB 118 have been completed. To be sure, tax provisions have always involved some element of estimation. In short, it is generally expected that the accounting for period-of-enactment items should not remain open solely in anticipation of new legislative or regulatory guidance.

2018 and Beyond

Beyond the challenges that companies face in completing period-of-enactment accounting, there are several complex issues to consider for the first time in 2018. SAB 118 applies only to the accounting in the period that includes the date of enactment and therefore cannot be relied upon in subsequent periods. As a result, there is no relief from the need to account for some of the more complex provisions in the Act that are now effective. However, it is helpful to note that the interim reporting guidance under ASC 740 generally requires the use of an estimated annual effective tax rate for the year as the mechanism to record tax expense for the period. This allows companies to put forth their best estimate in any given quarter and record refinements to that estimate as the year progresses.

GILTI, BEAT, and FDII are new international provisions that are being considered for the first time in 2018 annual effective tax rate calculations. The taxes on GILTI and BEAT target the erosion of the U.S. tax base by requiring the current-year inclusion of certain income earned by a U.S. shareholder’s controlled foreign corporations (CFCs) and by applying a minimum tax to related-party deductible payments, respectively. Alternatively, the Act attempts to provide an incentive for U.S. companies to produce goods and services domestically and sell them abroad by allowing a deduction for FDII. Adding to the innate complexity of individual provisions, these provisions also interact with each other in numerous ways, which must be considered when evaluating their impact. These provisions can also significantly affect the determination of FTCs by impacting either the computation of foreign-source income or the methodologies used to allocate expenses. Detailed calculations and modeling often are needed to determine the respective amounts and the overall financial statement impact.

For example, to quantify the amount of GILTI subject to U.S. tax, companies will need a significant amount of data, such as the tested income or loss for each CFC computed on U.S. tax principles, quarterly average tax basis in trade or business tangible assets, and available U.S. tax attributes. Furthermore, while the full amount of GILTI is includable in U.S. taxable income, Section 250 allows a deduction to reduce the effective tax rate applied to this income. To model the amount of deduction allowable to offset a U.S. shareholder’s GILTI inclusion, companies will need to forecast U.S. taxable income, including consideration of permanent and temporary differences and the utilization of net operating loss (NOL) carryforwards. These inputs then must be analyzed to determine the current-year GILTI impact. Quantifying the potential FDII benefit and BEAT exposure will require similar levels of effort. Determining whether a company is subject to these provisions, much less estimating the 2018 tax and financial statement effects, poses a significant challenge for many taxpayers.

Other provisions within the Act may seem familiar but nonetheless could alter companies’ accounting assessment. For example, the expanded restrictions on interest deductibility in Section 163(j) may result in indefinite-lived deferred tax assets for interest expense carryforwards that will need to be assessed for realizability. Similarly, NOLs generated after 2017 will have an indefinite life with no carryback availability, which will impact the sources of taxable income that may be available to realize the associated deferred tax assets recorded in the financial statements. Given this complexity, it is highly likely that the expected reversal pattern of existing temporary differences will affect valuation allowance assessments. Prior to tax reform, the scheduling of U.S. temporary difference reversals was necessary only in limited situations. Unfortunately, it appears that a scheduling exercise, which can be challenging and complex, will become more common and may, in many cases, be required.

Perhaps the most significant complexity that will affect future financial reporting will be how to address the various uncertainties that exist within the Act itself. In a number of ambiguous provisions, the operation of the law is unclear. Even when the statutory language is clear, many challenges have been identified thus far, including instances where applying the new law produces results inconsistent with expectations or what is understood to be legislative intent. Much of this is to be expected when overhauling thirty-plus years of established tax law, especially when considering how certain new concepts interact with remnants of old law. Many of these issues eventually may be fixed or clarified through regulatory guidance or technical corrections legislation. In fact, Treasury anticipates the release of twenty-five to thirty pieces of new guidance this year.

Nevertheless, under U.S. GAAP, companies must account for tax laws when and as enacted and therefore cannot consider any anticipated changes in tax law or expected future interpretations. To identify tax benefits associated with any tax position, one must first conclude that, more likely than not, the position will be sustained based on the technical merits. Generally, as future developments further refine the application of law impacting a tax position, the effects are recorded in the financial statements in the period such guidance is issued. This likely means that until future clarifications or corrections are issued, a company’s financial statements may reflect some of the unintended consequences that exist in the new law today. Transparent disclosures can help users understand the impact of tax reform on the company’s financial statements.

The Key Takeaway

Accounting for income taxes is a challenging area for many businesses, and the new tax Act has only added further complexity. Enactment of U.S. tax reform is one of the most comprehensive policy developments in many years and will bring with it complex, wide-ranging impacts to financial reporting. Companies will undoubtedly face challenges as they update their systems and processes to address the changes in their business, financial, and tax reporting. Moreover, expectations for future legislative and regulatory developments in response to tax reform will require companies to remain focused on the changing landscape.

Rick Levin is a partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and is its U.S. tax accounting services leader. Luke Cherveny is a partner in PwC’s U.S. tax accounting services group.