Many corporations currently face tremendous high-value tax uncertainty as a result of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), not to mention other longstanding tax risks such as transfer pricing. For some tax executives, these risks constitute familiar waters. For other tax executives, however, navigating these risks is less routine and may seem more challenging, especially if the corporation generally favors certainty and earnings quality over a few percentage points of effective tax rate.

Although many tax executives prefer to operate within the comfort zone of “should,” the major new rules added by the TCJA make that difficult. Indeed, when most corporations filed their 2017 tax returns, there was little or no binding guidance other than the language of the Internal Revenue Code itself, which was fraught with numerous ambiguities. Yes, at the time there were some nonbinding proposed regulations—also known as suggestions for comment—but not final or temporary regulations, which are currently entitled to Chevron deference. Likewise, the Internal Revenue Service had issued several notices related to Section 965 prior to the due date for 2017 returns. But again, sub-regulatory guidance, such as a notice, is not binding authority and is given deference only commensurate with its “ability to persuade.”

More and more proposed regulations have been issued since 2017 returns were filed. What will the regulations look like when finalized, perhaps after technical corrections to the TCJA? Although this answer is far from certain, if the proposed regulations are finalized within eighteen months of the TCJA’s enactment, under Section 7805 they may be retroactive and apply to the 2017 tax year. Thus, many return positions that were relatively certain when 2017 tax returns were filed may suddenly become uncertain due to subsequently issued regulations. In these situations, tax executives did not have the option to plan for or to avoid the uncertainty altogether.

Is Chevron Deference Itself Uncertain?

Will taxpayers and the courts have to defer to the final regulations once issued? Perhaps, but the U.S. Supreme Court is likely to revisit Chevron deference in the next few years. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who served as the Supreme Court’s swing vote for many years prior to his retirement in July, wrote in April 2018 in Pereira v. Sessions, 138 S. Ct. 2105, 2120-21 (2018) (Kennedy, J., concurring):

The type of reflexive deference exhibited in some of these cases is troubling . . . . [I]t seems necessary and appropriate to reconsider, in an appropriate case, the premises that underlie Chevron and how courts have implemented that decision. The proper rules for interpreting statutes and determining agency jurisdiction and substantive agency powers should accord with constitutional separation-of-powers principles and the function and province of the Judiciary.

Given its current makeup now that Justice Kennedy has retired, the Supreme Court seems likely to revisit Chevron and at least “tighten” it to some degree.

Finally, to the extent the regulations themselves are ambiguous, courts will struggle with the question of whether they should defer to the IRS’ interpretation of its own ambiguous regulations or, as did the Tax Court in Gottesman & Co. v. Commissioner, 77 T.C. 1149 (1981), rule in favor of a taxpayer’s reasonable interpretation when faced with regulatory ambiguity.

But, once finalized, the retroactive regulations may cause an uncertainty to spring to life and require a tax reserve as well as a Schedule UTP.

Charting the Levels of (Un)Certainty

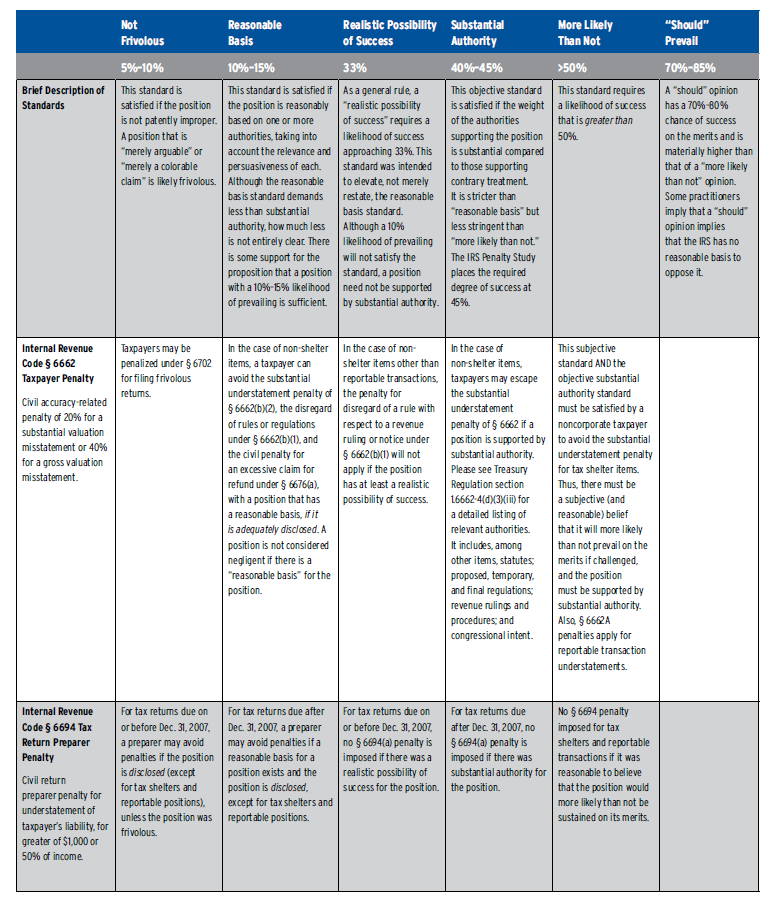

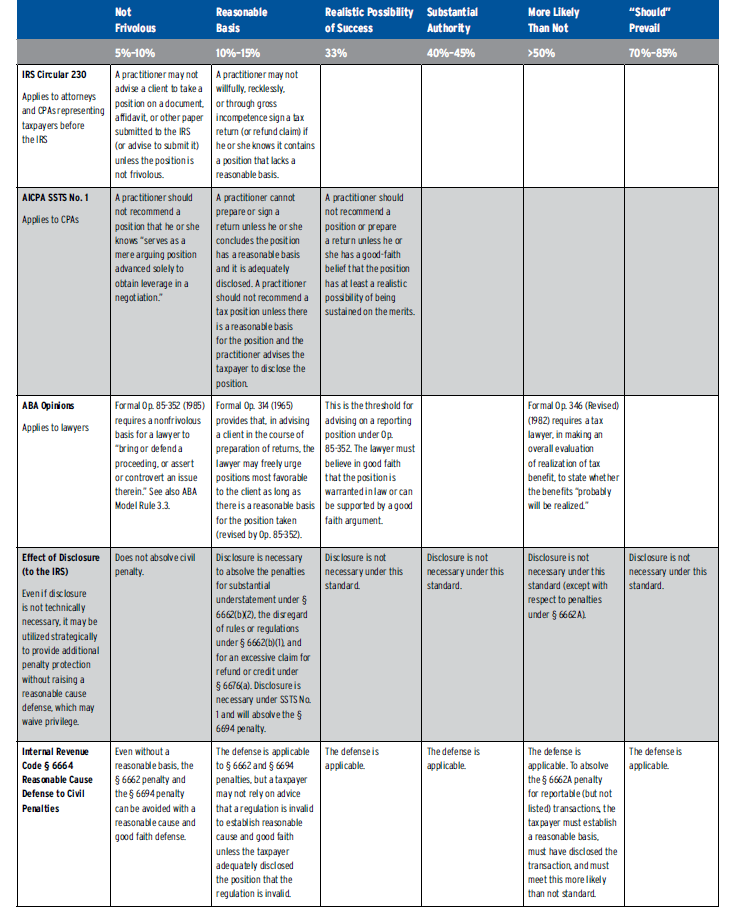

It may be helpful to step back and review the overall picture. The chart on the next two pages shows the range of (un)certainty that is not only legal but also ethically permissible. This chart can also serve as an important communication tool for discussions with nontax executives regarding the tax risks a corporation may face.

As the chart shows, the overall legal and ethical structure recognizes that significant uncertainty may be the norm, not the exception.

Tax Reserves, IRS Audits, and Disclosures

It is very likely that a corporation’s financial auditors, not the IRS, will first identify a significant tax risk. In response, the financial auditors may or may not require the corporation to establish a reserve. This obviously may influence whether a corporation must file a Schedule UTP for uncertain tax positions, which functions the same way Forms 8275 and 8275-R do for noncorporate taxpayers. This schedule and these forms may highlight issues for the IRS to audit, but they also generally provide additional protection against penalties, as do Revenue Procedure 94-69 disclosures.

For a disclosure to provide penalty protection, however, it must be adequate. Schedule UTP serves as adequate disclosure for corporate taxpayers and is generally required for (1) tax positions for which a reserve has been recorded and (2) tax positions where no reserves are recorded because of an expectation to litigate the issue when the taxpayer believes (a) the probability of settling the issue is less than fifty percent and (b) the taxpayer is more likely than not to prevail in litigation.

Normally, there is no requirement to file a Schedule UTP in later years unless the uncertain position affects more than one year. For example, if a Schedule UTP was filed for the 2017 tax year for a tax position that generates a carryover, generally no Schedule UTP is required to be filed for 2018. In contrast, a corporation may need to file a Schedule UTP if an uncertain tax position in 2017 creates basis that is utilized in 2018.

A caveat also exists for changed circumstances. For example, if a corporation takes a position on its 2017 return for which no reserve was recorded because the corporation determined that the position was correct, but circumstances change and in 2018 the corporation determines that the tax position is uncertain but does not record a reserve because it expects to litigate, the corporation must still file a Schedule UTP with the 2018 return for the 2017 position. (See Example 5 of the Schedule UTP instructions.) Many corporations adversely impacted by subsequently issued regulations may find themselves in this situation.

In fact, a number of corporations have taken return positions that they believed correct when they filed their 2017 tax returns, so no tax reserves were established or Schedule UTP filed for the position. Subsequently, proposed regulations have been issued that would adversely impact the return position once finalized. In response to the proposed regulations, some corporations have attempted to establish tax reserves, but financial auditors have refused to let them do so because proposed regulations are not binding authority. But, once finalized, the retroactive regulations may cause an uncertainty to spring to life and require a tax reserve as well as a Schedule UTP. (See Examples 2 and 5 of the Schedule UTP instructions.)

In the absence of a Schedule UTP, and in the case of an item or position other than one that is contrary to a regulation, disclosure must be made on Form 8275. If the position is contrary to a regulation, disclosure must be made on Form 8275-R. If neither Schedule UTP nor the forms are required, tax executives should carefully consider the strategic use of Revenue Procedure 94-69 disclosures at the commencement of an IRS audit.

How Long Will Uncertainty Last?

Historically, the rule of thumb was that the normal three-year statute of limitations created an eighteen- to twenty-four-month window from the date a tax return was filed for the IRS to start most audits—and if it did not, it was unlikely that the IRS would audit the tax return. Under the TCJA that window may have increased significantly. A six-year limitations period applies to an assessment of net tax liability due to pre-2018 accumulated deferred foreign income, omissions of Subpart F income or income from the new GILTI tax, or adjustments related to the transition tax. Even in the absence of extensions of the statute of limitations, six years is a long time. And, for some issues, this may be just the beginning. Keep in mind, and by way of example, that the ongoing Altera case is a challenge to the 2003 amendments to the cost-sharing regulations. As much as tax executives might hope that the TCJA uncertainties now on the table will not take fifteen years to resolve, that is nonetheless a possibility.

Tax executives facing high-value tax uncertainty clearly see choppy waters and potential storms on the horizon. Thorough evaluation and effective communication of these risks are critical to successfully navigating these waters. These are shared challenges best confronted together.

Levels of (Un)Certainty for Tax Return Positions

Assumes IRS audits merits of return position

Todd Welty is a partner at McDermott Will & Emery and chair of its tax controversy practice. Lowell Yoder is a partner at McDermott Will & Emery, focusing on cross-border mergers and acquisitions, global tax planning, and international tax controversies.