This article presents the challenges of collecting tax-related intercompany transaction information as well as common functional misalignments of intercompany-transaction-related responsibilities inside the multinational enterprise (MNE). It also identifies key intercompany transaction function subject matter expertise (SME) and aligns these SME units or individuals with specific intercompany transaction operations. This article furthermore explains the best ways to achieve this alignment. Finally, the author shares thoughts on how an MNE may justify an investment to better align intercompany-transaction-related responsibilities with core functional competencies to create a more effective and efficient intercompany transaction end to end.

Intercompany-Transaction-Related Challenges

When managing the corporate income tax expense, MNEs face an unprecedented challenge in collecting, analyzing, reporting, and disclosing detailed qualitative and quantitative intercompany transaction information. Robust intercompany transaction information is necessary for the corporate tax department to 1) effectively defend against transfer pricing (TP) adjustments by increasingly aggressive global tax authorities; 2) perform complex tax calculations called for by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, or TCJA (for example, BEAT, GILTI, FDII, etc.); 3) comply with extensive new or proposed substantive tax rules and related required documentation under various Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) initiatives; and 4) calculate and forecast income tax expenses, deferred tax account balances, and uncertain tax positions, among others.

Additionally, the TCJA’s international tax reforms incorporating a participation exemption, combined with a reduced twenty-one percent U.S. income tax headline rate, heighten companies’ exposure to permanent income tax differences for non-U.S.-initiated TP adjustments at the controlled foreign corporation level. As the owner of the consolidated income tax expense line, the corporate tax department is often the key stakeholder questioned if an adjustment to this line is necessary due to an ineffective intercompany transaction framework.

When managing the corporate income tax expense, MNEs face an unprecedented challenge in collecting, analyzing, reporting, and disclosing detailed qualitative and quantitative intercompany transaction information.

Common Misalignments of the Tax Department’s Intercompany Transaction Responsibilities

MNEs have been challenged to develop existing intercompany transaction processes and controls to keep up with the dramatically expanding requirements described above and the dynamic business transformations that technology enables. At the same time, since intercompany transaction processes and controls do not generate revenue, it is not uncommon for the corporate tax department to be called upon to solve “its” challenges, with limited investment in additional resources. Here are four examples of nonnative intercompany-transaction-related responsibilities that are sometimes housed inside the corporate tax function: 1) lead responsibility for identifying new intercompany transactions; 2) responsibility for calculating and booking intercompany transactions; 3) responsibility for developing financial reporting functionality to meet “tax-only” information requirements by, for example, disaggregating the cost of an intercompany service into its individual cost center and G/L subaccount elements; and 4) preparing new intercompany transaction agreements. As described below, intercompany-transaction-related responsibilities are best aligned cross-functionally with the units possessing the proper subject matter expertise (again, SME).

Aligning Intercompany Transaction Responsibilities With Subject Matter Expertise

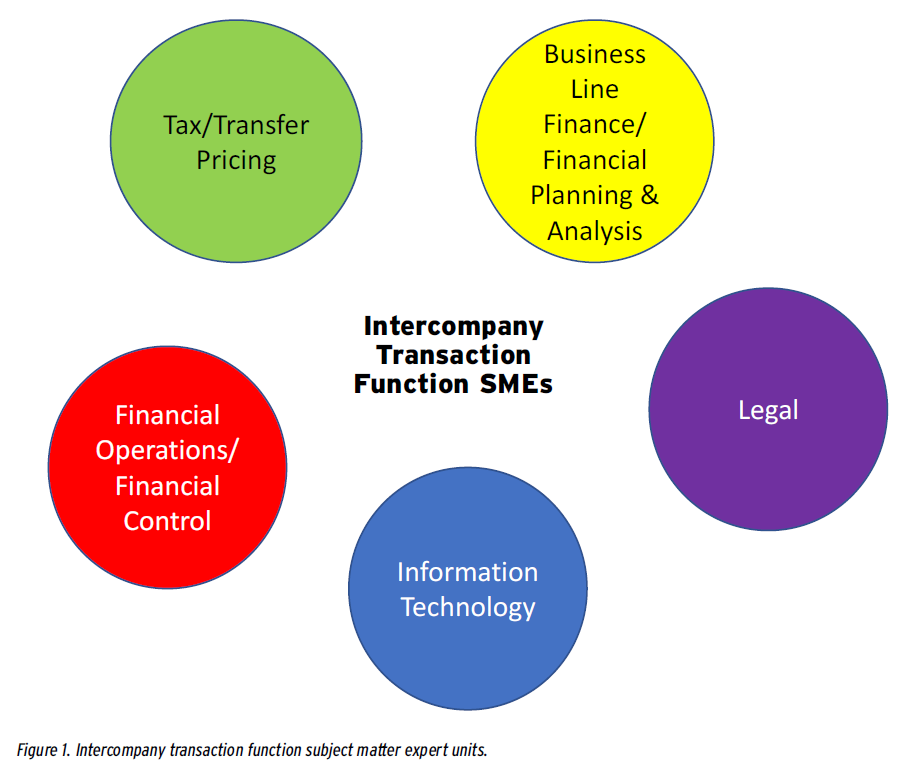

Notwithstanding that the corporate tax department is a primary consumer of extensive qualitative and quantitative intercompany transaction information, as an initial matter the MNE may wish to consider the thought experiment of whether a similar alignment of SME responsibilities for third-party customer transactions should be applied to intercompany-transaction-related responsibilities. Figure 1 identifies the SME units generally best positioned to contribute to an effective intercompany transaction framework.

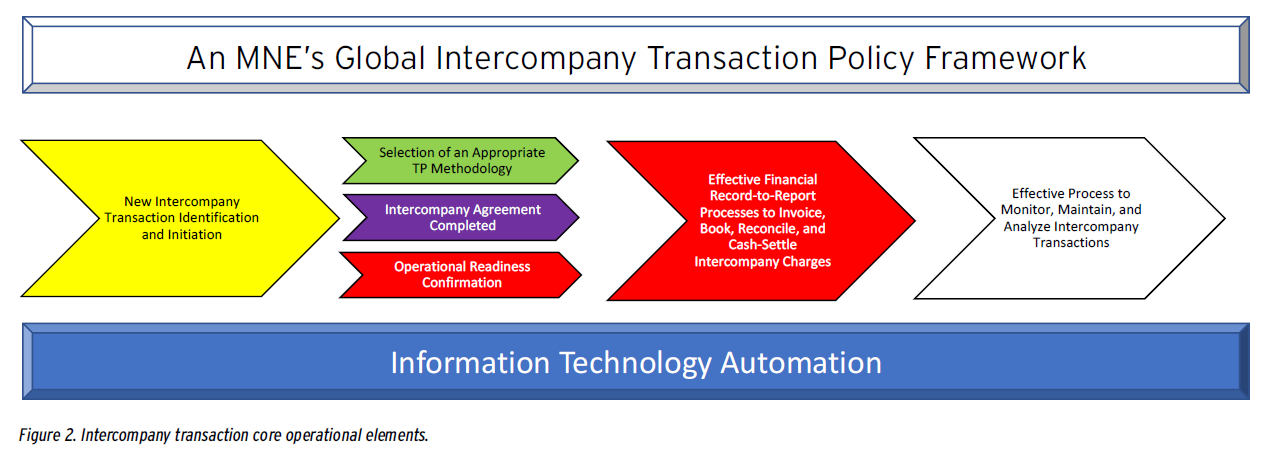

An effective intercompany transaction framework requires four essential operational elements: 1) new intercompany transaction identification and initiation; 2) selection of an appropriate TP methodology and operational readiness to ensure available data and processes to properly calculate intercompany charges based on the selected methodology; 3) effective financial record-to-report processes to invoice, book, reconcile, and cash-settle intercompany charges; and 4) a process to monitor, maintain, and analyze intercompany transactions to ensure timely consideration and action to update key inputs and outputs of the end-to-end intercompany transaction process.

Figure 2 identifies the appropriate SMEs for each of these core operational elements by using the colors associated with each function SME in Figure 1.

As Figure 2 illustrates, the intercompany transaction operational elements should align with the function SMEs, and in many cases multiple SMEs will collaborate to ensure that each operational element is effectively performed.

Best Practices to Ensure Alignment of Intercompany Transaction Functions With the MNE’s SMEs

A global intercompany transaction policy statement (a TP policy) sponsored by one or more MNE group senior management members (e.g., the chief financial officer, chief accounting officer, or chief tax officer) is an essential ingredient for an effective intercompany transaction framework and is a best practice. An effective TP policy is an accountable and therefore auditable declaration typically stating that intercompany transactions must be properly identified, evaluated, calculated, reported, documented, and periodically revalidated. A TP policy mitigates a common TP risk factor and is explicitly mentioned as a Master File business overview disclosure in the OECD’s TP Guidelines.

Helpfully, the OECD TP Guidelines explicitly recognize that tax administrations have an interest in seeing that MNEs are not so overwhelmed with compliance demands that they fail to consider and document the most important items. Accordingly, the OECD TP Guidelines acknowledge that a TP policy may include a materiality threshold for intercompany transaction documentation. However, regulators in the financial services or other highly regulated industries (e.g., public utilities) may expect additional intercompany transaction notification requirements or governance to be included in an MNE’s TP policy.

Since the TP policy is generally a high-level enterprise-wide declaration, it must have an underlying implementation layer. This next layer should describe roles and responsibilities and may also include operating manuals and procedures for intercompany transactions, training materials, RACI matrices, and other practical guidance (potentially in FAQ format) to clarify and align responsibilities. This implementation layer eliminates informal handoffs between internal functions that may involve unclear roles and responsibilities by establishing clear accountability, thereby optimizing internal expertise, creating collaborative efficiencies, centralizing responsibilities, facilitating automation, and streamlining processes.

An additional best practice is a quarterly intercompany transaction review among function SMEs and business management. This forum affords an open and collaborative dialogue among the business management and function SME participants across a variety of topics, including new business initiatives, process pain points or opportunities for process improvements, and resources. The meeting agenda and handouts may follow a standardized template that might include a current inventory of intercompany transaction flows and related invoiced amounts. Formal meeting output should be considered, which may include a list of takeaways with responsible parties and timelines identified. The meeting may be timed during the last month of each quarterly reporting period to allot time to resolve any identified concerns impacting quarterly operating earnings of the MNE or its affiliates. This meeting serves as a terrific opportunity for the corporate tax department (and other function SMEs) to stay informed and share meaningful input.

A robust intercompany transaction framework with active, continuous engagement from function SMEs can be an effective tool and enabler for the corporate tax function and

the MNE’s income tax expense line.

Moving Toward Best Practices

Given that the corporate tax department’s extensive consumption of intercompany transaction information affects key international tax and TP planning and compliance initiatives, and given that the department often assumes responsibility for nonnative intercompany transactions, a best-in-class alignment of functional expertise and intercompany transaction responsibilities across an MNE is clearly desirable. In addition, a misalignment of tax resources may suggest that there are other intercompany-transaction-related risks that do not impact the corporate tax department that can be mitigated by realigning responsibilities.

MNEs that want to bring their intercompany transaction framework closer to best practices may consider a cost-benefit evaluation. This cost-benefit evaluation should include the active involvement of individuals with intercompany transaction function SME. The collaborative findings of the cost-benefit analysis would then be presented at the executive management reporting level to which the function SMEs generally roll up (for example, the CFO). Consideration of the following potential benefits may help build the case with senior management to invest in enhancing the current framework:

- Can the MNE’s effective tax rate planning be enhanced if more robust and timely intercompany transaction data analysis and forecasting are available? For example, is there real-time participation of the corporate tax department in initiatives like supply chain rationalization, new business initiatives, or business reorganizations, with attendant financial modeling?

- Are there opportunities to centralize, streamline, and better control decentralized intercompany-transaction-related processes through technology and process automation?

- Is there an opportunity to bolt on intercompany transaction process enhancements to existing or future financial-management- and legal-entity-reporting-related transformation initiatives?

- Do tax reserve disclosures on industry peer financial statements identify potentially material TP reporting issues or tax examination risks attributable to gaps in the MNE’s intercompany transaction framework?

- Does the MNE’s current or past tax audit examination experience suggest there may be significant TP-related tax, interest, and/or penalty exposures to be mitigated (along with the resulting costs to defend) if the MNE adopts a more robust intercompany transaction framework?

In summary, MNEs face unprecedented challenges to compete and evolve globally with changing business, technology, and geopolitical conditions. A robust intercompany transaction framework with active, continuous engagement from function SMEs can be an effective tool and enabler for the corporate tax function and the MNE’s income tax expense line. A periodic cost-benefit analysis based on a function-specific evaluation across the core intercompany operational elements may be a prudent and relatively low-cost means to identify cost-effective intercompany transaction process enhancements. Even if major process changes are not in store, a cost-benefit analysis is likely to identify low-cost opportunities to better align functional expertise with intercompany transaction responsibilities while further sensitizing SMEs to the benefits of communication and collaboration.

Richard Goldberg, JD, CPA, consults with Fortune 500 and other multinational enterprises on technical and operational matters related to transfer pricing. He is grateful for the valuable insights that tax and transfer pricing leaders across a broad group of MNEs provided for this article.