The COVID-19 pandemic has wrought disruption and change in practically every area in which we operate, and its effects on the sales tax environment are no different. What is particularly interesting about the operation of the sales tax is that states and businesses are still grappling with the groundbreaking developments resulting from the US Supreme Court’s decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair in June 2018. The interplay between changes in how consumers purchase goods and services during the pandemic and the states’ ongoing reaction to Wayfair make this a particularly challenging time for businesses to determine how to comply with new sales tax obligations. This article examines how shifts in economic behavior during the pandemic have complicated sales tax legislation developed in response to Wayfair, leading to more uncertainty in how the states tackle sales tax issues in a post-pandemic, post-Wayfair world.

Changes in Economic Behavior During the Pandemic

Pandemic-induced changes in economic demand have caused consumers to reconsider in-person purchases and instead to use e-commerce to complete transactions. For example, in the past year, trips to brick-and-mortar stores within malls for in-person sales transactions have been either impossible, impractical, or, at the very least, largely discouraged. Although the economic carnage resulting from the pandemic assuredly led consumers to eliminate many discretionary purchases they otherwise would have made at a mall (not to mention the loss of many businesses themselves that depended on these purchases), consumers quickly became adept at shifting their economic behavior. Instead of the ad hoc mall run, they surfed the internet, found the best deal after searching through various websites and coupon codes, and, with an assist from a delivery company, received their items without having to step outside their homes.

The resultant increase in remote sales through vendors, often with the help of marketplace facilitators, has led to two intriguing revelations. First, the advent of Wayfair-style legislation requiring remote sellers and marketplace facilitators to collect and remit sales tax came at a particularly critical time for the states, given the revenue gaps states now face in light of the pandemic. The relative stability of the sales tax during the pandemic stands in contrast to volatile income and property tax regimes, which in many sectors are showing historic weakness. Second, in the pandemic environment, the annual economic and transactional thresholds requiring action by remote sellers and marketplace facilitators are becoming easier to attain, given the additional online activity of consumers changing their economic behavior.

Continuing Sales Tax Compliance Burdens

Whereas business conditions have remained tenable for companies that managed to pivot during the pandemic and accommodate customers through expanded offerings, more convenient delivery, and electronic and other services, the sales tax compliance challenges that these companies faced before the pandemic still exist. Figuring out how to determine whether a particular product is taxable or not in multiple states can be difficult, especially if the product is considered a mixed transaction in which taxable tangible personal property and an exempt service are provided at the same time. Likewise, determining the taxability of new revenue streams related to the pandemic, including pandemic-related products and surcharges, adds to the vendor’s risk of over- or under-collecting sales tax on these transactions. Furthermore, meeting all sales tax collection and remittance deadlines every month, documenting sales tax exemption certificates when applicable, and handling audits as they come can overwhelm a business consistently saddled with these tasks, especially when the effect of Wayfair legislation may have drastically increased the number of jurisdictions in which returns now must be processed.

Businesses that want to implement or restructure their sales tax collection systems to meet post-Wayfair standards now must navigate the logistical hurdles (and costs) of performing implementation themselves or potentially outsourcing this task to third-party providers for remote implementation. Given the timing of Wayfair and the states’ responses, 2020 was gearing up to be the right year for many businesses to confirm how to implement sales tax system changes and then move forward with that implementation. The effort in this area promised to be difficult enough without a worldwide pandemic. The pandemic magnified the broad reach of post-Wayfair laws for those fortunate enough to continue growing their businesses and made it nearly impossible to achieve a restructuring that could have been helpful in facing the pandemic’s economic effects.

Changes to Post-Wayfair Legislation?

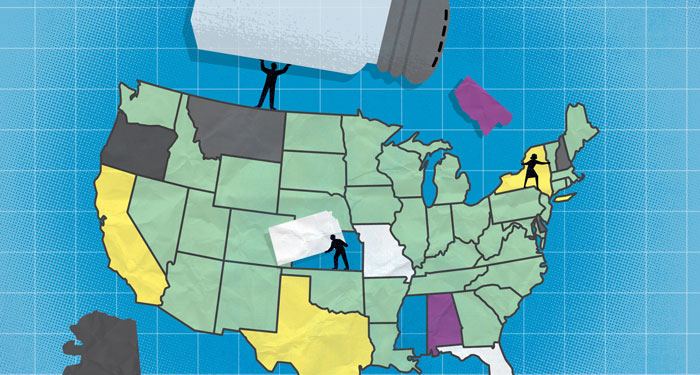

The Wayfair decision eliminated the need for a remote seller to have physical presence in a state in order for sales tax nexus to be established. Over the course of the next eighteen months, almost every state, newly empowered by Wayfair, adopted remote seller and marketplace facilitator legislation. This legislation imposes sales tax registration, collection, and remittance requirements for businesses selling or facilitating sales through a marketplace to in-state customers above a certain annual economic threshold (generally from $100,000 to $500,000) or an annual transactional threshold (generally 200 in-state transactions). State-by-state distinctions in definitions of what constitutes a sale, what periods must be considered to determine whether a threshold has been met, and what entities are considered marketplace facilitators have all proven challenging to businesses trying to determine where they might have to collect and remit sales tax. And, as noted above, the pandemic made these challenges even more far-reaching and complicated, in part because the economic and transactional thresholds that trigger remote seller and marketplace facilitator compliance became easier to meet in 2020 due to the new ways in which consumers shopped.

Given the states’ rapid legislative and regulatory efforts regarding the taxation of remote sellers and marketplace facilitators, it stood to reason that in 2020 states would revisit what they had hastily adopted after Wayfair. At the onset of the pandemic, however, most states decided to suspend or curtail their legislative sessions, generally by shortening sessions and addressing only truly urgent pandemic-related items on their agendas. As a result, states that might have considered tweaking the Wayfair economic thresholds or clarifying definitions governing these provisions did not have a chance to do so.

Will 2021 provide state legislatures with the opportunity to move forward once again with legislation focused on Wayfair and its effect on businesses? With the increase in remote economic activity and continuing fiscal challenges, even Florida and Missouri, two states that have been reticent to adopt Wayfair legislation, are now strongly considering it due to the financial fallout from the pandemic. At the same time, notwithstanding the comprehensive efforts of the Multistate Tax Commission and the National Conference of State Legislatures to provide thought leadership and model legislation, it will be surprising if states manage to act in concert to make their remote seller and marketplace facilitator statutes even incrementally more uniform than they currently are. And any action in this area presupposes that the state legislatures can meet without significant interruption from the ongoing pandemic, which could make 2021 the second year in which little beyond the pandemic itself can be addressed. Ultimately, remote businesses newly subject to post-Wayfair legislation may be hard-pressed to conclude that the sales tax world in which they have operated will become simpler in 2021 and beyond if a level of state legislative uniformity cannot be achieved.

Sales Tax After Wayfair as the Pandemic Abates

With viable vaccination options and continued vigilance with respect to social distancing, masking, and quarantining when needed comes the potential for society to obtain herd immunity to COVID-19 in the near future. Given what we have been through in the past year, we can only hope that, with these measures, the pandemic passes and life returns to a “new normal” later this year. When the new normal begins to take hold, state and local tax authorities are likely to ramp up sales/use tax audit efforts for several reasons. With the return to safe, in-person communication, auditors will be able to go directly to the taxpayer’s business to more swiftly review the sales tax treatment of transactions and associated documentation. At the same time, auditors have learned a great deal regarding audit efficiencies through technology in the past year. The combination of in-person and remote activity could result in quicker turnaround times for completing audits, generating assessments, and settling controversies. Likewise, the practical need for states and localities to generate revenue quickly, given immense pandemic-caused financial stress, could drive further efforts to streamline the audit process.

In trying to balance budgets, will state tax authorities solely concentrate on their newfound ability to impose sales tax obligations on companies in the wake of Wayfair, or will there also be attempts to address fact patterns pre-Wayfair? If ongoing litigation in this area involving the use of fulfillment companies to expand the presence of a business to a national market is any clue, then the ability to look to pre-Wayfair periods will remain an issue of concern for businesses. Specifically, vendors that use online fulfillment companies to sell goods to customers nationwide may have lingering pre-Wayfair sales tax issues they may never have envisioned, to the extent that their inventory was transferred into a different state in which the vendor had no relationship prior to the completion of the sale. In such instances, a state may allege that under the terms of the fulfillment arrangement, the vendor had technical ownership of its inventory in a state (without actual possession), resulting in physical presence nexus within that state.

As for relying on post-Wayfair legislation to generate sales tax revenue, one can expect significant evaluation of businesses using marketplaces as remote sellers and operating marketplaces as facilitators. Designed to prevent companies from making an end run around the sales tax even with remote seller rules in effect, states are still fleshing out the scope of the marketplace facilitator rules as adopted in tandem with the remote seller rules. Differing and often expansive definitions of who qualifies as a marketplace facilitator may force state tax authorities to consider who must collect and remit sales tax in multiparty transactions in which more than one party may technically fit the definition of a marketplace facilitator.

At the same time, situations may emerge in which a business might want to serve as the sales tax collection and remittance agent for multiple jurisdictions even though it may not technically qualify as a marketplace facilitator under the governing state statutes. These situations could arise when one of the facilitating parties in the marketplace has significantly more experience in collecting and remitting tax on behalf of others than the marketplace sellers and customers have—and may be incentivized to do so for a service fee. One would think that states would be receptive to parties that are willing to collect and remit for the state, even if they may not fit existing marketplace facilitator statutes, though guardrails to ensure that these entities follow applicable registration, collection, and remittance rules would be needed.

As the drive for revenue shifts into full gear, states are likely to evaluate whether accelerating sales tax payments through legislative adoption is a viable strategy. In the first legislative adoption of such a provision during the pandemic, Massachusetts will require monthly return filers with $150,000 or more in sales or use tax, room occupancy tax, or meals tax liability in the prior calendar year to remit taxes collected through the first three weeks of a month by the twenty-fifth day of the same month. Tax collected the rest of the month will be due with the next return the taxpayer files, due on the thirtieth day of the following month (replacing the current practice of filing and paying an entire month’s taxes by the twentieth day of the following month). It remains to be seen whether, as a matter of convenience, the state will allow taxpayers to file one return that includes payments for both the current and prior months.

One can imagine a world in the relatively near future in which easy-to-use technology behind point-of-sale remission of sales tax becomes affordable and accessible to most businesses. At that point, states could go beyond Massachusetts’ measure and require immediate remittance of sales tax, along with relatively instantaneous and considerable tax filings. Of course, although it can be argued that accelerating sales tax payments results in a short-term timing benefit for states that go this route, it’s difficult to argue with simple math. If the total sales tax collected does not significantly grow in response to the acceleration policy, the financial benefit to the state for implementing the policy will be insignificant. Further, the cost and burden of performing daily collection and remittance activities for one or more states could be extremely concerning for businesses and dampen overall profitability, consequently reducing the income tax that is ultimately collected. For the time being, states will closely watch Massachusetts’ experience with its acceleration provision.

In addition to audit vigilance, aggressive post-Wayfair interpretations, and the potential for accelerated sales tax collection regimes, businesses should note that states will also look to two time-honored approaches to expand the reach of the sales tax: tax rate increases and tax base expansion. Although neither is politically attractive, the need for revenue and the desire not to make devastating budget cuts that could stall an economic recovery coming out of the pandemic may necessarily lead states down one of these paths.

To counter arguments that a general sales tax rate increase is inherently regressive and falls on those least able to afford it, states could raise tax rates on specific products, akin to Connecticut’s “luxury goods” tax adopted several years ago. One negative consequence of such a policy is that, if taken to the extreme, adding numerous state and local tax rates applicable to certain products complicates the sales tax compliance process. Tax base expansion appears to be the more likely approach, particularly as the shift to a digital economy has prevailed even more during the pandemic. In the coming year, several states are expected to consider either specified gross receipts taxes on digital goods and services or an expansion of their existing sales tax to cover digital goods and services.

Finally, as a potential counterpoint to the revenue-raising measures states are likely to take in the coming year, states could be constrained from becoming too aggressive by the simple fact that everyone wants their favorite businesses to survive and eventually thrive in the post-pandemic world. One way in which states could give the most affected businesses an opportunity to beat back the economic effect of the pandemic is through targeted sales tax relief. At the beginning of the pandemic, several states offered short-term relief from sales tax filing and remittance requirements to businesses particularly impacted by the declining economy. But relief was far from universal.

Maryland is one state that has continued to provide relief during the most challenging periods of the pandemic. The state recently extended the time to file sales/use tax returns, along with accompanying payments, for the December 2020, January 2021, and February 2021 tax periods to April 15, 2021. In addition, Maryland Governor Larry Hogan recently offered as part of a proposed emergency stimulus and tax relief package a sales tax credit for certain small businesses of up to $3,000 per month for up to four months. The Maryland legislature is likely to consider the relief package in upcoming months.

Conclusion

Clearly, the pandemic has left an indelible mark on our economy and our collective psyche. As the pandemic begins to recede in the rearview mirror, we might sense that some consumption patterns that arose as a matter of necessity will remain for a very long time. This shift may permanently amplify the role of remote sellers and marketplace facilitators as significant and essential actors in our economy. It can only be hoped that policymakers recognize that the powerful tools they now have to generate significantly more sales tax revenue in a post-pandemic, post-Wayfair world need to be used responsibly to ensure a robust recovery.

Jamie Yesnowitz, a principal at Grant Thornton LLP, is the firm’s state and local tax leader in the Washington National Tax Office.