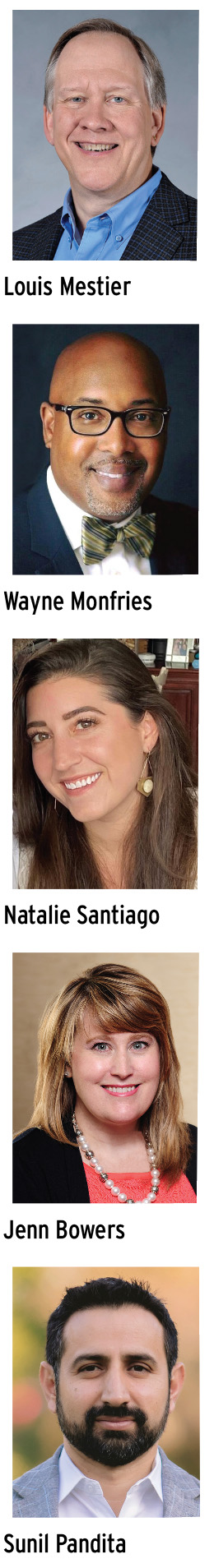

What does the tax department of the future look like? Not easy to predict, right? At the TEI Midyear Conference, we gathered a stellar panel to discuss crucial questions that impact every Institute member. Below is an edited transcript of half of that discussion, but not to worry. You can find the entire edited transcript on our website. The session, moderated by Anthony Sciarra, included these participants: Louis Mestier, Wayne Monfries, Natalie Santiago, Jenn Bowers, and Sunil Pandita.

Introduction to Roundtable Discussion

Anthony Sciarra: Good morning, everyone. I hope that you’ve had a wonderful couple days here at TEI. Before  we get started, I just want to take a quick second to thank all the TEI staff and leaders for all the hard work and effort that goes into pulling this together. As a former in-house tax leader, the resources and the collaboration that come out of these conferences is just tremendous. So, thank you to all the TEI staff and leaders for the effort. My name is Anthony Sciarra. I’m a partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers, and my practice focuses on tax department operations, whether that’s people, process, or technology. I’m here today to moderate what I think is going to be just a phenomenal panel. We’ve got great representation from the lens of in-house tax leaders. We’ve got great representation from the lens of executive tax recruitment as well as from a technology perspective. What we hope to do today is really give an update. Where do we stand? What are we seeing? How are our organizations differing in how we’re approaching return-to-work? How is technology playing a role, not only in our staff that we have in our operations today, but in how we recruit and who we recruit? With that, I’ll turn it over to our panel to do some quick introductions.

we get started, I just want to take a quick second to thank all the TEI staff and leaders for all the hard work and effort that goes into pulling this together. As a former in-house tax leader, the resources and the collaboration that come out of these conferences is just tremendous. So, thank you to all the TEI staff and leaders for the effort. My name is Anthony Sciarra. I’m a partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers, and my practice focuses on tax department operations, whether that’s people, process, or technology. I’m here today to moderate what I think is going to be just a phenomenal panel. We’ve got great representation from the lens of in-house tax leaders. We’ve got great representation from the lens of executive tax recruitment as well as from a technology perspective. What we hope to do today is really give an update. Where do we stand? What are we seeing? How are our organizations differing in how we’re approaching return-to-work? How is technology playing a role, not only in our staff that we have in our operations today, but in how we recruit and who we recruit? With that, I’ll turn it over to our panel to do some quick introductions.

Louis Mestier: Louis Mestier, senior director of tax for Cook Inlet Region Inc. Been a member of TEI for over twenty years, and we have completed the TEI Corporate Tax Department survey, so I’m going to serve as a resource for that on the panel.

Wayne Monfries: I’m Wayne Monfries, the global head of tax for Visa. I’m also the senior vice president for TEI and happy to be on this panel to provide context for the tax department of the future. I noted that none of the men are wearing ties on here, because the tax department of the future, on return to work, is no ties [laughter].

Mestier: That’s right.

Monfries: We’re just not going to wear it anymore.

Sciarra: There was a real question this morning when I woke up, whether I put jeans and a jacket on, or an actual suit.

Monfries: Wearing a tie in this panel would probably be against everything we’re going to talk about [laughter].

Natalie Santiago: I’m Natalie Santiago. I work on the team at TaxSearch. We’re the largest executive retained search firm in the country that works exclusively in tax. I’ve been working in that space for about seven years now. Excited to be here.

Jenn Bowers: I’m Jenn Bowers. I work for Fortive Corporation, which is based outside of Seattle, Washington. I’ve been a member of TEI for something less than twenty years—maybe like five. But I’m telling lies; it’s more than five. Also, happy to be here.

Sunil Pandita: Hi, everyone. My name is Sunil Pandita. I’m the president of the corporates division for Thomson Reuters. As you all know—you all are our customers—we serve the Big Four, but we also serve every corporation in the world from direct tax, from indirect tax, property tax, transfer pricing, you name it. I am the newbie on this panel; this is my first TEI ever. So, I’m excited. Last couple of days have been a lot of fun. Thank you for your partnership and your insights.

What’s Changed?

Sciarra: Just to give you a little behind-the-scenes view on how we prepped for this panel, every time we tried to talk about the agenda, we just talked about all the issues for an hour. So, we’ve sort of done this conversation a number of times, and every single time, it’s gone in a different direction. What we’re hoping here is to take the cover off on really what’s top of mind. But what’s top of mind for this panel is not top of mind for everything. So, if you’re thinking of something that we’re not talking about, please do come up to the microphone and let us know so we can address it and have that conversation. Why don’t we get right into it—Jennifer, how has your function changed? How has your view on running your function changed, whether that’s retention, recruiting, training, all of the above?

Bowers: A lot of things have changed. I took my role as head of tax just before the pandemic started. So, I had this opportunity where I needed to present myself as a leader to the team. At the same time, I couldn’t see any of them together in person. Then, also reorganizing my team—I waited until last summer to do that because I got my bearings with the team before changing the team organization. One of the things I wanted to do in my new role was to have more frequent touchpoints with the team, which is dispersed globally. So, I was going to travel more, but that didn’t happen. Instead, we set a cadence of a virtual meeting with the global team twice a month; we reduced that to once a month as time went on. I also created touchpoints with different leadership teams within my organization. We ended up with an opportunity to connect and figure out what everyone is doing and plan together. It unified the team in a neat way. So, I was brought in [to lead] and at the same time we ended up changing how we work together from a virtual perspective. Overall, as we are coming out of this, we’re bringing back those elements of in-person collaboration—which I still think are important for an organization. You get more creativity when you’re together in the room versus all the work we tried to do virtually. It was OK, but it’s better in person.

Sciarra: Wayne, from your perspective: We talked a bit about the in-person meetings, but you had some interesting tidbits to share on strategy around making the whole experience as inclusive as possible also.

Monfries: Yeah. I think that we’ve learned that being virtual does work. I started my job at Visa in the pandemic. For two years, I’ve been virtual, and I haven’t really met many of my team or many of my colleagues at the company. What I’ve learned is, we used to have these global meetings, and you’d have five people in a conference room, and one or two people on the phone or on video, and the people on the video never felt like they were as invested in the meeting as others. So now we’ve learned that being on camera and everybody’s the same size box, everyone feels invested in the meeting. So, for my global meetings, I’m going to continue to have them virtually even when we happen to be in the office. We’ll just sit at our desk and do it rather than have five people in a room and two people on video, because we want to retain that ability of inclusion and people feeling like they are being heard equally as someone sitting in the room.

Mestier: What you’re talking about is technology here, right? And so, to cite the [TEI Corporate Tax Department Survey], six in ten respondents say their company implemented some new technology as a result of the pandemic. So, that was huge. Mostly software, some hardware. That was to enable all of this sudden rush to running virtual operations.

Pandita: Let me add to that, Louis. You brought up the technology point. I think that’s so important. We also do a survey every year for all the tax departments. This year, roughly 870 people responded. And what Louis articulated is [the] same: Actually within the department, sixty-seven percent said collaboration has not suffered. Twenty-five percent said collaboration has actually gone up, because everyone gets the same size box. And tax departments, we’re mostly multi-jurisdictional. Ten percent said it has suffered. One point that’s important is, like Jennifer and Wayne, I also joined Thomson Reuters in [the] pandemic [laughter].

Sciarra: So, everyone’s new. Everyone actually, other than Natalie up here, I think, has a new job during the pandemic [laughter].

Pandita: So, first-time connections, you know, getting face-to-face, I think that part suffered quite a bit, and so I’m excited that everyone’s here. And technology is a big enabler, to your point, Louis.

Collaboration—Internal and External

Sciarra: One of the common themes that we just heard in this commentary is around the concept of collaboration. Whoever wants to answer this, jump in. The thought of collaboration is one thing; the type of collaboration is another. Collaboration in the tax department being one, collaboration outside of the tax department, tax being, really, the number one user of data in the organization that’s not always clean and requires follow-up, as we all know. How have you been able to address that “tax-out” collaboration point throughout the pandemic and now as we return to work?

Monfries: I personally think it’s been harder, because I’m a personal person, right? I like to get to know people. I like people to get to know me. I think that creates a better working environment. Tax is difficult, and people often don’t want to understand it. But we need to use their data, and we need it in a way that we need it. So, they need to understand what we do. Your survey said collaboration didn’t drop in the tax department, but I think when we were talking, you said that collaboration outside the tax department did suffer, and that’s because people need to talk to us and see us and get to know us and work with us. Within the team, it’s great. We can do it virtually—collaboration is still there—but we lost that connectivity with our partners outside of the function. And I think that that’s important to get back to as we return to work or emerge in this new environment.

Bowers: One of the things I did—I mentioned I reorganized my team in the pandemic—I created a new function, which was focused on our relationship with the business. We’re a very decentralized organization with twenty-three operating companies. All have a president and a CFO and run independently. But we need information from them. They also make changes to their business all the time. We didn’t connect with them as much in my first fifteen months in-role, and that was not going to be sustainable. So, in creating a focused attention where I took someone and I said, “Your job is just this,” it was a big risk because there is a lot of ambiguity for the role. But we found ways to connect with the operating company leadership and be part of their virtual meetings. We have also identified individuals within the team who now have an opportunity to be what we call a “tax partner” to one of these operating companies. And then we set measurable things on how can you demonstrate that you are making that effort. Because “successful” may be very subjective. We needed to find ways to measure that tax partners were able to connect with the business. Depending on how your organization is, it could look differently. It could just be that you need to focus your attention on various functions within your group. It took a specific, intentional investment of effort.

Sciarra: Did you need to go sort of upward to get approval to create that role, or did you just try it, show that it works, and then say, “Hey, guys. Look what I did.”

Bowers: I just did it. And then I reached out to all these leaders of the organizations to say I have this new person: “You’re going to please include them,” and they’ve been really responsive.

Mestier: One thing that worked for us: When I came on board, we had a division that was very entrepreneurial. I was told to keep hands off, let them do what they do. So, I approached it as tax being a resource to them. Make them want to contact tax when they see something that they know may have implications instead of them having to deal with it after the fact or us having to deal with it after the fact. So, it’s kind of a push from them, and it worked out real well. They really see that. At first, you go in, “I’m from tax; I’m here to help,” and then they start to believe you when you spot some issues and you remedy those issues, then they start to become aware of them.

Pandita: One thing to add, which is the collaboration point, Wayne, you talked about between tax department and accounting or audit or other finance functions, is data. And frankly, what we have seen across multiple customers is investment in that data and making sure you have as much as possible single source of truth. When you make GL changes in one place, they propagate with communication in a remote environment across the board. And that’s another trend we are seeing, more and more people paying attention to the data. First is garbage in, garbage out. Second is propagating that across departments. I think that’s again to your point, Louis—technology is helping quite a bit in there, with some machine learning, with some artificial intelligence. It doesn’t have to be that perfect. But I am still with Wayne—I’m also old school, and I would love for people to come in person at least some days or weeks, because that collaboration is more than data.

Sciarra: I think you raise a really good point, which is, for so many of us, we become the first line of defense as sort of an internal audit function for the controllership. We have a different lens on results than a lot of folks do, different level of materiality. And so there can be some difficult conversations there. I have to imagine some of those conversations are even more difficult with people who have never met each other in person. And with the constant change and—in what I’ve seen at least in most organizations—a continuing change in operating model for finance. So, Jennifer, you mentioned about that business partner, you emphasized that. Wayne, have you seen any change in your finance organization during the pandemic or post-pandemic that you’ve had to adjust to?

Monfries: No, I haven’t really seen a lot of changes. I think that everybody’s embraced the virtual working environment. I think we try to do things that bring people together, and not just jump on the call and go straight to the business at hand, but also have some informal time—what have people been doing, noticing people’s background, having conversations about that. And so, we’ve been able to build relationships and develop them better, or successfully, in this by just being people.

Sciarra: Sounds funny, right?

Monfries: It does. We talk about the greatness of being together in person, but if you’re in person, you get up from your desk, you walk to the other desk, you say, “I need this or that or whatever,” and then you go back to your desk or your office. This way, we’re actually making an effort to try to get to know people. Frankly, when you’re working from home and you got your background, people are coming into your life. That’s probably been a good thing—for me. Some of us might say, “No, I want to blur my background.”

Bowers: Wayne has a great background; there’s lots of fun stuff to look at on the walls [laughter].

Back to the Office

Sciarra: I’m terrified to come into a meeting without the blur feature on [laughter]. Jennifer, just going back: Are you back in the office? Are you expecting your teams to be back in the office? Where do you stand?

Bowers: Through most of the pandemic I was on a committee of people where we’re trying to figure out how to open the office back up. We never officially closed; we just said don’t come in. There were some people who would still need to come in for mail or whatever. But short trips to the office were, like, I don’t know, apocalyptic—plants were dead. Someone needed to do something about the condition of the office if we come back. We talked about returning to the office last summer and we started a rollout with an invitation of “Folks, you know, if you want to come in the office, we’ll order lunch for whoever is there.” And then it just was clear, nobody was interested in coming back to the office despite the effort of a warm welcome. But it became apparent that our leadership did not feel fully remote was the sustainable thing that we wanted. Our style of collaboration does involve a lot of tools similar to Lean or Six Sigma, and there are ways to do that virtually, but our management wanted that in-person experience. Our manufacturing people have been coming in the whole time. I didn’t really draw the short stick, but I was assigned the responsibility to be the person to say to the corporate team, “So . . . we’re going to start coming into the office a couple days a week; two or three, good. Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday would be nice.” And I had been prepping my team for a long time. I’d been going in for a couple days each week and I would talk about how it’s hard to change your process. I’ve also just been telling people to be kind with themselves. If there is a day you need to come into the office, and something goes awry, don’t worry about the fact you didn’t make it to the office. Just take care of what you need to take care of and try again. Over the past month of March, two days a week for most of them, a few with one. Some have issues with needing to figure out a pattern for their childcare, and it will look different for them.

Monfries: I think the big thing about return-to-office or work-from-home is the flexibility. I think to lead the function in the new environment is to be flexible, and to work in the function in the new environment is to be flexible. So, we’re going to go back and we’re going to go a couple, two days a week, and we’ve selected those days. But we want you in the office maybe fifty percent of the time over a course of a month. So, you pick those other times you come in. But if there’s a meeting—let’s say it’s on a Friday—and we need you in on a Friday, then hey, I’m going to say “I need you to come in this Friday.” And the person working for you can’t say, “Well, I only come in on Tuesdays and Wednesdays.” No. I need you to be flexible, because if you don’t need to be in on a Tuesday one week, then don’t come in on Tuesday that week and we’ll be flexible. You have to manage it in a flexible way, to Jenn’s point, understanding people’s personal situation and working with them on that, because now—with regard to recruiting, retention, and the like—we all need to lead in a flexible manner so we can adapt to what people expect and what they’ve expected over the last couple of years.

Mestier: It comes down to performance, right? If they’re getting their work done at home, and it doesn’t impact anything else, like maybe a meeting they need to be at, that’s fine. It makes the employee happier. They stay around. Everything works out well. I’ve been really lucky, because I have a small team, they all want to come in five days a week. They have distractions at home. My wife is a gig worker; she works out of her home office. I want to leave her be. Some days, we have to stay home because the snow is too deep, but they come in five days a week otherwise. And there’ll be Fridays there that, “Oh, it’s the tax department in today,” and nobody else in the office, but we’re fine with that.

Training and Development

Sciarra: How has it impacted, if at all, your training and development programs? Louis, maybe you’ll start.

Mestier: I’ll refer to the survey again. One of the things that’s really upticked in the survey are virtual seminars and conferences. We didn’t really even have a question back in 2012 about virtual conferences and seminars, right? So, the training that I get at my level is a lot of webcasts, but I think the software for the virtual conferences has a long way to go. [Everyone nods in agreement.] It leaves a lot to be desired, especially on the networking side of things. So, that has not advanced as much as I thought it would in these two years with this great need, but it is advancing. Travel—you know, we didn’t have travel budgets for a long time. It seems like forever. But now it’s starting to free up, and so that’s why we’re all here now. So, it’s kind of an evolving thing, and we don’t know what the future brings. We never know what the future brings, but we just kind of adapt to it and get our needs met as best as possible.

Monfries: Yeah, I hear you on the technology, particularly around the networking. But as we emerge into a new phase, I think the realization is that the training will be virtual. People don’t travel if they don’t want to travel. If they want to network, then they’ll come, like you all have come. But the virtual nature of it, people have just sat at their desk or sat at their home and gotten their training. Shameless plug for TEI: I encourage [you] to take the modules from these conferences and, as we return to office, have that as a reason for the team to get together in a conference room and view a session and talk about what it means for the company. That’s the piece of training that we missed: How do you apply the training to the company? Because everybody’s doing it individually.

Pandita: I think one thing to add. What we picked up from our surveys is this thing called “taxologist,” where tax people are now beginning to say, “Some of our people need to be more tech-savvy.” And so to your point on training and enablement, we see more doses of, you know, at least understanding what is a data lake, how do you extract data, how do you do GL flows? Now, not everyone goes through it. But like five percent, ten percent of your people are becoming more tech-savvy. The other part is, at least from our side, what we are doing and we discussed this is, we used to only hire very seasoned people. And frankly, we don’t have enough of them. So, we’ll have to go relook at enablement of some people coming out of the schools, some coming out of the Big Four, which are earlier in their career, and then groom them for the roles that they need to take. So, not just the medium but the actual content of enablement also had to kind of change.

Sciarra: Sunil, you mentioned an interesting point there around different skill sets or desires based on, let’s just call it tenure demographics of some of our staff. Are any of you seeing a difference—and this is a question that actually came in—are any of you seeing a difference in desire or ability to return to work based on demographic lenses, whether that’s age, tenure, or otherwise?

Pandita: I can start. We did a survey—and I’m curious, we have not discussed surveys—

Sciarra: We have a lot of these surveys [laughter].

Pandita: We did a survey for 25,000 people; 18,000 people in Thomson Reuters responded. Here are a couple of insights. It didn’t matter by gender. It mattered by seniority. The more senior you went, the more people wanted to be in the office. The middle of the pack didn’t want to be

in the office. As you go lower in tenure, they

want to be in office again. So, there was just [an] interesting dichotomy.

Bowers: That’s like my anecdotal. My niece started at Deloitte this past summer. She has told me, “I want to go work in the office, meet people, and ask my questions.” So, that’s that lowest band. And my group is the exact same way. Then there is the middle band. There are only a few here or there that are eager and excited. And then as you get higher up in responsibility, they consider the expectation of senior leadership, the response at that higher level has been “I know I need to support our leaders, so I’m going to be in the office.” But the middle band feedback is consistently, “I’m doing great. I could do this from home.”

Monfries: I see it as corporate culture–driven. I don’t have anybody who’s saying they don’t want to come back in the office, but I’d love to hear the perspective of the workforce that’s out there, and as you talk to people who are looking for jobs, what do they want?

Bowers: Yeah—the candidates are probably the most honest.

Santiago: Yes. It’s been interesting seeing how it’s laid out. We ran an initial survey that found I think about seventy-six percent of respondents were looking for, ideally, a hybrid schedule, some in office. And I have found with lighter candidates—ones that are more at the entry level—I think they’re starting to recognize how much more difficult from a training development standpoint it is to get that up to speed without some of that face to face. Especially a lot that have entered the workforce on a remote basis. I do notice some more consistency with people in the manager, senior manager, usually wanting a little bit more flexibility. People might have young kids at home, family dynamics to account for. For the leadership-level positions, though, most heads of taxes or people that are rising heads of taxes, looking for those roles, recognize—with the just degree of interface with the business, the management aspects, training, developing talent—most of those roles you’re going to do most successfully on at least some in-person. Fully remote situations might be an exception there if everybody in the department’s operating on a virtual basis. But for the most part, I think what we’ve seen the lean toward is hybrid, probably the biggest demand. Time will tell.

Monfries: You touched on an interesting point about the collaboration, and I want to come back to training. One of my things when I am president next year, we’re going to talk about leadership development, and we’ve been talking about that for a while. But leadership development is the thing that we’ve missed being virtual, right? Being able for staff to come in and see a leader and how they operate and learn from that. The things that your niece wanted to learn by going in the office, we’ve missed that. And so this is something that we have to think about as we start to work differently, because you’re not getting that leadership development just by looking at someone on the screen.

Santiago: Yeah. You raise a really good point there, because it’s not necessarily the technical development that’s a challenge, but really developing people on the EQ, softer-skill-set side. A lot of companies are still trying to figure out how to do that on a virtual basis. It’ll be interesting to see how some department leaders kind of rise to meet that challenge in doing that in a more virtual basis.

Mestier: Not only do we have development needs going forward we need to address, but we have this gap now. We have this two-year black hole where they didn’t get developed. So we have to catch those guys up.

Sciarra: Are you thinking about that deliberately, with training programs, maybe different paths of training programs, for folks who have joined during the last few years versus those who are returning to the corporate culture that they left two years ago?

Monfries: Haven’t thought about it in that way, just thought about making it happen from a mentorship perspective, a sponsorship perspective—reigniting those kind of programs for everyone. Because I think those programs also need buy-in, so the other person has to realize they want to do it. It’s a two-way street, but making the program available.

Bowers: I think depending on the size of your organization, you may have internal things that might be available already. We have a few things, but not a ton. I am declarative about support for these types of opportunities with my team. Meaning, for example, I found a leadership training program that has been going on for several years in our market, and they were going to do it in person this year. So, I had a message sent out: “If anybody wants to attend this, please register. There might be a group discount for me if you all want to go.” There’s also other interesting things out there. We did a team dynamic program with a third-party company where we were trying to understand where our team was in the evolution of a team, and that was insightful. As Wayne said, you have to be intentional about carving space for it and declaring that you want to see that investment.

Budgets

Sciarra: Talk a little bit about budgets. We mentioned budgets and the virtual options. Are you seeing a challenge to an attempt to return to in-person networking events from your CFO or anyone else? Is it opening back up? What are the thoughts around that?

Mestier: We’ve really supported it. Our CFO has yearned for it. When I got there, I got there before the budget process started for the company. And so I planned in-person events out; they’re in my budget. My budget got approved, and the CFO supports it completely. My predecessor was really involved with TEI, so my boss knew about TEI, and he knew the value of any professional organization. But not my whole team is going to TEI. They have different needs for different things, and I’m picking and choosing, but this is one of the most cost-effective resources that we have. For Alaska, everything is going to cost more when you come down here. I budgeted two people to come to this conference, and they fully support it. So, it really depends on the CFO.

Monfries: Yeah, I think, in general, CFOs are going to be loath to give up the savings they’ve seen on the T&E line, but there’s a realization that it’s necessary, particularly if your culture and your CFO believes in that collaborative approach, whether it be travel within the business or travel for training. I think those budgets are there. I also think, from a technology perspective, we’ve spent a lot on technology, setting people up to work virtually. That number will come down. So there will be a little bit of a trade-off.

Pandita: One more thing I’m hearing on this topic, which is allowing people to travel, is a fear of Pillar Two and a lot of changes coming tax-wise. So a lot of CFOs are saying, “If you need to go meet your peers and get knowledge of what’s actually going to happen so you’re ready ahead of time.” I’ve seen a lot of travel approvals come just from that fear that “what if there’s a lot of changes?,” especially domestically. Also in Britain, because of Brexit, a similar pattern follows. In other countries, I see less loosening of the purse, if you may.

Bowers: I’m similar to Wayne in that I have an organization that values that collaboration. To me, my budget is not exactly the same number before the pandemic, but it’s fine and I can support things. I think Louis brought up an interesting point: Sometimes you have to educate your leaders on why this is important. I’ve always been fortunate enough to work with leaders who could articulate the value of developing our tax staff to make sure we’re current on the laws. It’s a unique area. The resource of training is not perhaps as available internally. It’s important to go find those external sources that can do it. Sometimes you have to sell it a bit and you will have mixed success, but if you never ask, they don’t have the opportunity to tell you no.

Sciarra: You don’t ask, you don’t get.

Monfries: Tax adds a lot of value.

Bowers: Yes, we do.

Sciarra: Just piggybacking off of Sunil’s comments on Pillar Two, there’s always the fine line between selling value and sort of scaring some folks that I need some more resources because I’ve got things, whatever those resources are—money, technology. Have you had to react to that in any way? Are you getting reception inside your organization? Not only do we have this watershed moment that we’re coming back to work, but we also have the potential for new, very broad, very reaching regulations and requirements that may change the way our function works. Any thoughts around that topic? Jennifer, start with you.

Bowers: I think that we’ve been moving toward improved technology for a while. Guidance for GILTI came in and then these final foreign tax credit regulations. All of this creates a lot of complexity for analysis. We’ve increased head count. We have more specific investment in technology, but I don’t know if we are unique. I’m also curious if you’re seeing that companies are more replacing talent, or are they growing their teams. Natalie?

Santiago: Seeing a lot of growth, and that’s part of the reason why we’re seeing such a high demand, I think, for talent in the market. Companies are trying to [grow their teams]—especially if they were not properly resourced through tax reform and kind of had to learn, “Hey, may be good for us to be ahead of the curve and kind of ready to ensure we have the resources available to meet these new challenges.” So, it’s led to a lot of creation of head count from what we’re seeing out there.

Monfries: I do see there is less pushback when you ask for resources, and I don’t know if it’s because of the things you mentioned, the complexity. I try from an OECD perspective or legislative perspective not to make it too complex for those outside the function, and just try to be real specific about what it means to the company. And that’s not really in the conversation on resources, but the complexity of compliance is. So, when we start talking about technology versus head count and what we’re doing to comply with all the rules is when we start to get into the conversation of people. I have a CFO who’s very open to that conversation because he wants to make sure we’re compliant. I’m sure all of us do. So, I couch it in that way—just getting the work done because it’s complex rather than in the tax technical.

Mestier: And referring back to the survey, which is why I’m here [laughter]—or at least one of the reasons I’m here, I’ll say—it’s really obvious that, as far as recognition performance measurement priorities, what is that based on, especially during COVID? It’s really always for our position. Number one, performance measures lack of surprises. Number one—seventy percent of the respondents said that. I’ve found that when I’m coming in a new position like I did recently, that I get somebody’s attention with fear—you know, bring a problem, bring a solution, show them you can solve the problem—and then I keep their attention with savings. That’s kind of how I approach it. I was lucky enough to be in a situation where I saw a problem, provided a solution, but now, with training, with coming up with new ideas, you get one idea from this conference, you know, it’s a multiple or fifty or 100 easy of what you paid to send people to the conference. So, I just reiterate that each time. Sometimes the message takes a while to get through, sometimes it gets through quickly.

Hiring and Retaining Talent

Sciarra: We’ve talked a lot about resources. We’ve talked a lot about changes in the department. Maybe this is a good time to pivot to what I think we’ve got a number of questions coming in and may be on the minds of the folks in the room. How are we supposed to keep resources, and how we supposed to hire resources who are in the marketplace with multiple job offers, all asking for an extraordinary amount of money and saying that they’ll maybe come in once or twice a year [laughter]?

Monfries: Yeah, Natalie. How we supposed to do that [laughter]?

Sciarra: Natalie, how do we do that?

Santiago: It’s a good question, and I think one a lot of tax leaders are trying to navigate right now. To say it’s been an interesting few years in hiring has been an understatement. I think most people here at TEI, you’ve seen the market on the hiring side cycle between a more employer-driven market versus candidate-driven. I think it’s safe to say right now, we’re definitely more of a candidate-driven market. We have a very high demand for talent, low supply. There’s two big factors, I think, that are kind of driving some unprecedented challenges that we haven’t really seen in prior markets. Even the most seasoned tax professionals who have been working in tax for 20-30 years have said something feels different about this one. And it is. I think one new thing that’s kind of thrown a wrench in things is remote work. It’s created a lot of headaches from a retention standpoint. Competition is very intense out there for talent. In the past, you’d only have so many companies to compete with in your local market. Now, with remote being more prominent, your people are getting contacted for roles across the country at a rate we haven’t seen before. So, it’s created a lot of turnover in these functions. And it’s also made it harder for a lot of employers to stand out from a hiring perspective. That’s led to a lot of salary inflation, companies, firms alike trying to find incentives to bring people in. So, you’ll see a lot of salary inflation, promotions being accelerated, and more flexibility for work arrangements. Right now, remote work is a pretty small portion of the market. From initial numbers that we ran, it’s less than 12%, probably, of departments going fully remote. But that number is probably going to be increasing as we see more companies—even in hybrid or full office—making exceptions to retain people or bring additional people into the door. We’ll have more statistics and updated data points as part of our tax hiring outlook, so I’ll definitely give everybody access that want those data points later this month. On top of all of this, we’re also dealing with a huge demographic shift. You guys have already kind of referenced it here. We actually ran some new statistics, and the numbers we found were a bit startling. We found that just in the past two-and-a-half years since 2019, over 20% of heads of taxes have retired and left the profession. Twenty-five percent of the No. 2s in departments have either retired or moved into those No. 1 roles. So, we’re dealing with a huge loss of legacy knowledge. And this is in-house advisers and the external auditors. And it’s just beginning. Currently, 48% of heads of taxes are baby boomers. They are going to be retiring soon. And 40% of the No. 2s behind them are also baby boomers. So, this is only compounding upon some of the supply-and-demand issues that we’re seeing. I think it really ties into how critical development of talent is going to be in terms of really navigating these challenges. Probably the hardest department for us to recruit out of would be not the ones paying the most money or providing flexibility—those help; don’t get me wrong—but it’s the departments where the tax leadership has really taken the time to invest in the development of their people. They understand the career objectives of their top performers and they’re getting game plans in place. They’re thinking three steps ahead about succession planning. Recruiting out of those departments—that’s our Kryptonite. So, I think the more that departments can prioritize the development of their people—and also doing that in more of a remote world, leveraging technology to be more effective with that—that’s going to really be key moving forward. And probably my biggest piece of advice to tax leaders in terms of retaining talent and being able to bring new talent into the door: Build your brand as a developer of your people.

Mestier: Being on the other side of that fence, searching for a job during the pandemic for about six months, there are a number of employers that create their own problems. Not just finance people, but HR creates a lot of barriers to the process not only taking a much shorter amount of time, but also being successful in identifying the right candidate. I’m sure it’s all over the organization, but I just dealt with finance and HR from a lot of companies. There’s a lot of people that don’t know how to conduct effective interviews. I got the question of, “Where do you want to be in five years?” [laughter] “What are your greatest weaknesses?” It just got comical. I almost laughed every time.

Sciarra: If you could be any animal, what animal would you be [laughter]?

Mestier: Yeah! I just want to have a placard just to have a canned answer, because I knew it was coming. But there are those companies that compress the interview process, that got to the point, that knew what they wanted. We kind of talked also, because the market is equalized all over the place, that I saw a number of super-specific job descriptions that may fit two people on the planet. When you apply and you know that you’ve got 90% of the stuff, and you immediately get a rejection letter, you’re going “Something’s wrong.” And then, six months down the road, that position’s still open. And everybody says, “I don’t know why we can’t get applicants.” It’s because the gatekeeper’s keeping the door shut.

Santiago: Yeah.

Mestier: I think finance and—I’ll be nice to HR—HR also needs to really focus on what’s important and how to identify if a candidate has those talents that they need.

Santiago: You raise a great point. We can’t keep waiting out for the unicorn candidates, especially in this market. Candidates have a lot more options. I think the more that tax leaders can really educate upper management, they can educate HR in here’s the realities and where we’re at in tax. And we’re not like other industries. We’re a captive labor pool. It’s not like we can just bring talent in from outside the U.S. in many cases with the complexity of the tax code.

Monfries: I don’t want to dispute anything you said about the process, but I think the way we get after it is a term that we talked about here this week: being “people leaders” rather than “function leaders.” We have to own the hiring. If we see candidates, or we see a quality, or we see somebody we like, we got to get HR to go do all the legwork and push them, but we got to own it. We were successful in recruiting people during this by actually going out, owning it ourselves, and pushing HR to take the next step so that we’re not lingering for two and three months before we get back to somebody. We have to be people leaders. And that brings me back to your comment about development and why people leave. I’ve always taken it as personal when people leave, because I think being a good leader is you’re leaning into their professional development, and you take ownership for that. You want them to know you care about their growth. So, when we talk about budgets, we get budgets for technology because we’ve got to get our people to not be spreadsheet jockeys, and they’ve got to be more tax people, because that’s what they came to do. So, when we can invest in technology that allows them to do the work, then they grow. When we understand who they are, take the time to meet with them and know what their professional path should be or they want it to be, and we lean in to help them, people will stay. The best compliment I got recently was when we had an opening and someone who used to work with me at a different company called and said, “Hey, I’d love to come back and join your team.” That’s the compliment that we should be looking to get as we are people leaders.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Pandita: Just one thing to add: Wayne, you are declaring well about different dimension to retaining and attracting talent. At Thomson Reuters, 45% of our employees are females. So, how important is diversity and inclusion in hiring as well as retaining the talent? Because there is a demand-supply sap. So, I’m thinking about what are you seeing in the market, Natalie?

Santiago: It’s a challenge in tax, especially now with ESG becoming more forefront, the focus on diversity. And probably where that’s going to be hardest for tax is in that area. Almost every company we work with prioritize looking at diverse pools of candidates. I think we’ve done very good, as you brought out, in increasing gender diversity. Where it’s a little bit more difficult in tax is just in terms of the racial diversity there. I think the more that we can start to implement strategies in the short and longer term to really do what we can. Part of, I think, the crux of this is reliance on Big Four for hiring. The Big Four do go recruit out of the top-level schools, they get the top talent. But in those programs and in those schools, tax really hasn’t done a great job marketing itself to a lot of the diversity students. So, we do lose a lot of talent to the people in finance and other areas outside of tax. I think the more that either department in a longer term can really work on developing training where they can recruit talent at the entry level—you know, go to the schools and be able to do the on-campus hiring—is a longer-term solution. But another, in the short term, I think, is really putting the pressure in terms of the outside advisers that you work with to really prioritize diversity on the teams they have working with you on engagement.

Monfries: We were talking about this a little bit before. In-house tax departments typically hire experienced people. If we want to make a change in the profession and what the profession looks like from a diversity perspective, I think we have an opportunity to push back on our service providers—which are the training ground that you mentioned—and say, “Hey, when you bring your service team to me, I’d like for it to be a diverse service team.” That will get the consultants to go out and hire diverse candidates and train them, because when we pay their fees, we know sometimes we’re paying a lower-level staff person for a training. So, if we get them to train, then the pool of hiring becomes more diverse for us, and we have a long-term approach to changing the face of the profession.

Mestier: Recently we decided to outsource about eight partnership returns, just a compliance nuisance that we had. We decided to go with a large local firm that made the most cost-benefit sense to us. And the first thing I did when I got the names of a few firms was I went to their webpage and then to the owners and leaders page. The first firm I went to it was like the high-fiving white guys. It was all pasty white. They had a few females on there, and I went “No, I don’t think so.” So I went to another firm that had more diversity. It was obvious that they had more diversity. Now, in our market, I haven’t found enough diversity for what I’d really ideally like to have, but at least we’re going in a direction that will promote that change, and that’s how you reward that change.

Pandita: A couple of things, Louis. And great examples across the board. Many years back, it was “uncool” to demand of suppliers “I need this kind of profile.” It’s actually cool now. I have another business, like tax, I have a legal business, and I see lawyers demand from the law firms “I need this much racial diversity.” And it’s not just you’re going to a people who’s going to show up diverse, “the number of hours you work on my project have got to be 30% diverse,” and they can demand it. And there are tools right now to track that level, and I think it’s a very powerful point we make across the board. You have the power, you have the pen, you have the check to frankly go drive the transformation. It’s not going to happen in one year, but I think if the mindset shifts, we could drive it.

Monfries: I like that Louis made it foundational. It was a baseline for who he was selecting, not after you’ve gone through and then you check the box at the end. It was a baseline for you. That, I think, is a great approach.

Santiago: Yeah, I like that, too.

Bowers: I’ve been asked: “If I was to look at your team, what is the, you know, the makeup of your team?” That’s an odd question; I don’t want to have to go tally them. But I was pleased; I feel like we have good diversity. There are some gaps from ethnicity like Natalie brought up, and it’s really hard to fill that gap because of the shortage of talent. So, we need to go back to how can we be creative in building talent? I feel like we could bring in an entry level and come up with a way to train them by cycling through different areas of tax and see where their greatest strength was. Then, hopefully, that was a good fit in the long run. When it came down to choosing the headcount I was adding this year, I was asking for five people to fill resource gaps and I just couldn’t ask for a sixth one, not this year. While I didn’t ask for this entry level role yet, I keep it in the conversation. It’s about building our diversity, and you’ve got to start that conversation. We all have to make this investment so that there are people others who are similar can to look up to in these roles. When I started in the Seattle market, I think there were two women who were a head of tax. And then recently, someone put together a list. I was so pleased; there are about 25 of us, and it just feels great to see the change. I think it is a marathon, but you have to make a real diligent, specific effort.

Monfries: I want to say there’s long-term efforts, and there’s short-term efforts. But the short-term efforts, we have to accept that it’s hard. I’m a black tax professional. I know it’s hard. I look at my team, I say “I wish I could do better.” But we have to actually make an effort. We have to make an effort to do it. We know it’s hard. My boss would tell me when he first put out for this job, the recruiters brought him a nondiverse slate. And he said, “Well, these are all great, but I still want some diverse people.” You have to push them to look. People are out there; they have to find them. They’re not just jumping out saying, “Hey, I’m here.” You have to put in the effort to find them, and you have to force your talent acquisition team to work a little bit harder.

Sciarra: Yeah, I think that raises a couple of points that we’ve heard. One is as business leaders leaning in to the recruitment process, right? Not just allowing it to be a check-the-box, robotic exercised by recruiters and HR professionals. That certainly lends to the points on diversity and also the diversity and skill sets that we need inside the tax function. Just sort of going back to the recruiting process a little bit, Natalie, maybe you could talk a little about it. Diversity is certainly something that I’ve seen at least in recruiting into the Big Four; are there other aspects of roles that are attracting candidates? I mean, we do routinely, in Big Four, we get questions: “What is your diversity and inclusion policy? “What kind of groups can I get involved in?” And this is coming from nondiverse candidates as much as it is diverse candidates. So, are there other factors like that that are being brought to the forefront of recruiting discussions today?

Santiago: Yeah. I think, especially with how much we’re in such a candidate-driven market, you’re going to get a lot of requests in different areas. A lot of that’s just around kind of the individual and what they’re looking for. I think hiring authorities are going to have to get a bit more creative in terms of being able to bring qualified candidates to the table, for instance. And with all the challenges that remote work and some of these other dynamics in the market, those are some silver linings. Just looking at remote work, as an example: In the past, if you had a qualified candidate who you might not be able to afford, tough luck. Now, you might be able to still entice that same candidate with, “Hey, we’ll provide some flexibility to work remote.” There’s more ways that we have ability to stretch to bring in the talent we need to meet that individual’s needs. I think probably the ones that have been most successful and where we’ve seen get the traction are in departments where the tax leaders have built their brand and have the track record of really bringing on, developing quality talent. Because even when those departments experience turnover, it’s much more easy for them to bring quality talent to the table, because if their people are leaving, it’s typically for roles where you’d be crazy not to take that. I think that the development aspect is still very key there in addition to any benefits, perks.

Sciarra: Has the involvement of the head of tax in the recruitment process increased sort of down to more junior levels than perhaps in the past due to the crunch on resource availability?

Santiago: Yeah, and it’s the hardest pool to recruit for, just because of the demographics. We have a very limited pool of talent, and everybody wants to hire at the mid-manager levels out there. Heads of taxes have really had to be much more of an advocate with HR and upper management, educating them on the realities of this market and getting more hands-on involvement that’s needed to bring that lighter-level talent to the table. And those are going to be some of your most critical hires longer term, because like we mentioned, you’re going to have to accelerate a lot of those millennials and Gen Z talent at a much faster rate than what we’ve seen in prior years. If you’re not getting involved in those, it’s a good time to start.

Monfries: Learned something new today [laughter].

Technology

Sciarra: One of the things that we hear quite a bit about in the tax function is the role of technology. Natalie, maybe we’ll just stay on the recruiting side for a second. What are the expectations of the candidates in the marketplace today for the availability of technology when they come into an in-house tax role?

Santiago: It’s pretty essential now, especially at lighter talent. They’ll know pretty quickly on in determining their attractiveness to that department, how integrated they are from a tax-technology perspective. I’ve seen a lot more desire in that lighter talent pool to learn and really get more hands-on in the tax-technology side. I think a lot are wisening up: “Hey, I’m either going to have to really round out my skill set and leverage this, or I’m going to be the one finding my role potentially being subject to automation,” in certain areas. So, yeah, I would say we get a lot of questions in terms of how tax departments are leveraging technology internally.

Bowers: Speaking of Wayne’s comment that we’ve been paying for the development of technology professionals for many years, it is interesting—it does feel like there are more candidates with technology experience available and also interested in working inside the tax function. We’ve added a few people in the past six months, and two of them very specifically in the recruiting process talked about the desire to be more involved in the process of a whole tax function rather than just going and solving some technology thing or delivering a product. They really wanted to have more insight. We hired another fellow who was working in a technology team, but he just wanted to do more on the technical side of tax. At the same time, he brought a lot of technology experience he could share with the team. So, there’s been a lot of change; coming up back to that point of investing in our future. As Wayne said, we’ve been paying for a while, so now we can hire it.

Sciarra: And maybe just a follow-up question there for some context, because I know we’ve got representation from organizations that are large, they’re small. How many folks do you have in your overall tax function, and how many would you say are primarily dedicated to a technology role?

Bowers: Globally, we have 60 full-time employees in tax, and five that are full-time technology and three consultants, so eight.

Sciarra: Wayne, how about you?

Monfries: We have about 60 in the tax function, and we use an in-house company financial services technology group that supports us.

Sciarra: Louis?

Mestier: Four. We’re entirely reliant on IT to support us, but we’re at the bottom rung of the automation ladder. We’re scaling those rungs, especially this year. So we’re looking forward to get more evolved, so you can see what people are fearful of that, what people are embracing that, and you just have to deal with change management as you go.

Sciarra: Great. Thank you. Sunil, maybe we could just give us a little bit of a broad lens on what you’re seeing in the marketplace as far as technology in the tax function. How has that changed over the course of the last two years, and where do we see it going?

Pandita: It’s a great question. I think it’s a continuum, but three things to me personally stand out. First is I think regulation across the world, and given everything that’s happening, is getting more complex and actually not complex. So, that’s driving quite a lot of change. Second part is everyone, including my 8-year-old daughter, seems to have less patience [laughter]. So the amount of time they give us to do stuff is like, “OK; why can you not do it?” So, a lot of business functions are turning to tax and say, “What about what-if analysis? What happens if this? Can you tell me what my marginal tax rate will be?” I think that’s another big thing that is driving. And third part is, I think, the data. The data part about—whether you’re using sales tax, VAT, GST, any part—more and more execs are demanding end-to-end view of the data and not just part of the data and the leap of faith on the other. So, I see those three trends actually driving a lot of change on the technology side. But I’m curious on whether they resonate with a panel or not.

Mestier: Data, data, data. It’s amazing, because it’s a mindset. I’m not an IT person, but I know a database, I know what it’s made up of. I know how you get stuff, and I know by looking at it when the output is correct, right? It’s kind of changing a mindset. When you’re used to cutting and pasting into spreadsheets and doing all these things on the side, and I see spreadsheets grow and models grow, and I sleep less at night when that happens, I’ve learned to rely more on what I’ve always called “one source of truth,” right? As tax people, we’re kind of being relied upon to bring all the data together, make sure it stays true, and make sure there’s a way for other people to access it at some point in the future. We operate a lot predicting the future, but most of our job is dealing with the past. So, we have to maintain that data, and we have to be IT-savvy in doing that and build the relationships we need to make that happen.

Bowers: I mentioned before we have a lot of subsidiaries. We probably have 60 ERPs that we’ve got to get data out of, so, we rely on those subsidiaries to get us information, but then we have to have a way to put it together and consume it. It’s still a little clunky despite much investment. But I do think that there are some unique tools and we’ve made investment to train people how to use them. We can aggregate data much faster and we use other tools for flex analysis that actually make the review and the data-sensitivity process much better. I think you just have to go after it. My advice to anybody who’s early in the process of improvements and technology is always to ask “What thing is hardest to do every year?” It doesn’t matter what it is. “What’s the thing that’s the hardest to do, and how much time do you spend doing it? Well, let’s figure out how to do it in less time.” That’s always been my strategy. We have been focusing on transfer pricing analysis and segmented P&Ls, and I’m pleased when the team reports back, “Yeah, this thing used to take us three weeks and data from all these places, and now we can get it done in like a half an hour!” My response, “Fantastic!” That’s what I really advise: Give people the creativity to go figure out how to do it better and faster, because then you free up all that time you can spend doing research and analysis and the stuff that may be—it depends on what you find fun, but I like planning—more fun.

Pandita: Do you feel that affects morale of people, not having to spend a lot of time collecting data and arguing whether this is the right thing?

Bowers: I feel like there’s also job satisfaction, like, you created something, and I’m proud of this. You understand it better when you make that investment in it, too.

Monfries: Yeah. If you’re using clunky tools that people are taking hours to do something that should take five minutes, then you’re going to lose that person. You’re going to lose those people, because they’re going to go somewhere else that has invested in the technology that makes their life easier.

Bowers: Particularly the folks who can contribute both ways. Maybe they are savvy in technology, or maybe they’re not actually bringing their best talent to the table, which is, you know, planning or whatever it is you need them to do.

Sciarra: When we talked a lot about retention, recruiting. When you think about those accomplishments that you just laid out and the motivation, are you finding yourself challenged to balance impact and results or performance ratings for your staff for those who are, sort of, let’s just say, working very hard to find some creative planning solution which has the potential to be really impactful versus those who are getting really creative in automating away 300 hours a quarter? The genesis of my question is you used to be able to look at that and say, “Well, those are two different people,” right? Very clearly two different people. And now they may be the same person. That may be the same talent pool. How are you balancing that?

Bowers: I think the recognition is definitely there for both of them. I guess I’m not quite sure what your question is. Am I seeing that the talent is becoming the same person?

Sciarra: Let me ask in a slightly different way: Is there a specific performance criteria that you’re applying for that, let’s just say, efficiency automation drive versus the more traditional tax skills?

Bowers: I want to understand the efficiency of hours or the process. Another way that I’ve been trying to measure or evaluate is to consider efficiency. We needed to accelerate our close process, which was a goal that we had set for this year—and we did accelerate it by more than three weeks for year-end; I’m so proud of the team. But you have to start by identifying what’s the barrier to getting something done earlier? For example, if a sub-process takes a week—how can we make that a day? So, I it is around that contribution [of efficiency]. I think you can find ways to connect it to the bigger process or function.

Monfries: I think you got to put a process improvement, process efficiency goal in everybody’s plan for the year. I think you can reward it that way. I think the other way to look at your question is for me to say I’m not going to reward someone simply because people are saying, “Oh, So-and-So works so hard; they’re here all these hours.” Well, if they’re doing it inefficiently, I’m not rewarding that. And so, we put the process efficiency goal in. And you say, how can you do this differently? It pains me when we put together a plan—and we’re all finance people, so we signed up for this—but when we put together a plan that during the year end, we’ve got to work through Fourth of July. Like, really? Because I really value people spending time with their families, and when we build in the process, that is something that will drive people away, then let’s find a different way to do it.

Santiago: Yeah; I feel like you won’t be able to afford to not have as much efficiency in terms of the process, procedures. Tax departments are being asked to do more with less, increasingly.

Sciarra: Faster.

Santiago: Yeah. And you’re not going to be able to free your people up to do a lot of the more strategic, high-value-add work if they are so bogged down in the day-to-day. Candidates, people on the team, they’re affected by it. When we do a lot of the transformation kind of work, it typically attracts quite a bit of talent. I think there’s definitely a shift in mentality out there where it’s something more of a focus.

Mestier: In every place I’ve been, I’ve always started with the question “Why are we doing this?” And if the answer is, “Well, that’s the way we’ve always done it,” that’s the wrong answer. Absolutely the wrong answer. Can we do it better? Can we do it faster?

Sciarra: Can we just not do it at all?

Mestier: Can we do it more accurately? But the first question is always “Why?”

Bowers: Particularly if you’re delivering something, and you don’t know where it goes in the process, if you’re like so far out of it—I don’t usually see this in tax, but sometimes I’ll notice this from finance or IT, who sends out various information on a schedule. Just this past month, I thought, “Oh, I haven’t seen my reports for the year on actual spend for the first two months; I wonder where those are?” I sent the person a note to ask; she responded, “Oh, we’re only going to do those quarterly now.” And I think, “Great, because I only looked at them once a quarter, so that’s perfect” [laughter]. They figured out I didn’t need those monthly. You should evaluate what’s the actual need, because it’s true—you could be doing stuff that you don’t need. Sunil when we were planning for this panel, you had a statistic, departments spend 50% of their time wrangling data or something like that?

Pandita: Yeah, I think a couple of things. One is when we surveyed people who use—“effectively” is the important word—software tools versus using Excel, they could save 50% of the time on data prep at least, or more. Because that’s how effective that can be. But you have to use effective tools. Second thing is I think you mentioned the beginning, what’s happening demand side, but supply side, which is technology side, many things are of, I would say, commercial grade. Cloud is of commercial grade now. Lot of artificial intelligence, machine learning algorithms are of enterprise-grade, OCR technologies, especially if your form is deterministic, you can use those kind of technologies. So I think whatever your journey is, I would say it’s very unique to that company. You should not look at some other company and say, “Tomorrow I want to be there,” because it actually takes a little bit of time. And frankly, the incentives are different. Some do it for efficiency, some do it for better tax planning. Some want an end-to-end view because their execs are demanding it. One of the eye-opening moments for me was saying, “Sunil, how come head of HR or CFO shows up to a board meeting with very clear understanding of granular data with benchmarking, and I just show up with a tax rate?” and then I have to use a lot of words to explain it, because to actually create those detailed reports, my team has to put a lot of hours. And frankly, I get that report almost three hours before the close time. So I would actually use that time to move it early and more detailed and be more buttoned-up. I think you mentioned, Louis, data is the holy grail. It takes time, but tech has improved a lot in the last two years, not just for tax, but across the board. Tech has improved quite a bit, which should help. So, if we as tech providers are not serving you the right way, you should push us. You should challenge us and say, “This is not the user experience I demand.”

Mestier: I think one of the symptoms of that is, again, in the survey, technology used by tax departments, 94% use spreadsheets, OK? I really personally think that’s a symptom, right? Because why do you put stuff in the spreadsheets? Well, a lot of times because you have to manipulate the data, right? And so, if you really look at why spreadsheets are being used, if they’re using correct data pulls, if you’re getting straight off the database and you’re just in there for a little while and updating some really customized stuff, I get it. But a lot of times it is a symptom.

TEI’s Corporate Tax Department Survey

Sciarra: Louis, you mentioned a couple of data points on the survey that seem pretty interesting. Can you just tell the folks how they can get access to the survey and other information that is there?

Mestier: Sure. So, this survey, we started it in January of 2020. It went through the beginning of COVID and into the heart of COVID, and so we added a number of categories. We focused it at chief tax officers, or what seemed to be the chief—the most senior tax member that’s in your organization. And we have a hundred questions, a very detailed survey, a lot of data in the survey. It’s 10 or 12 different broad categories, but it’s invaluable. The last survey that was done was fantastic, but it was done in 2012, I believe, and so it’s been a while since we’ve updated this survey. Right now, this week it will be available on the TEI website for purchase. Everybody had their chance earlier; if they filled out the survey and submitted it, they will get the survey for free.

Sciarra: Always the benefit of spending the time.

Mestier: That’s right. It will be available to members for $175 and to nonmembers for $350. It will be available this week, and we’ll announce it when it’s on the website.

Sciarra: Fantastic, thank you. Well, thank you all, panelists, for the robust discussion. Hope you all found it interesting and insightful. Wayne, if you want to just give us a couple closing remarks on the sessions as a whole here, that’d be great.

Monfries: On behalf of TEI and its staff, the committee members that all worked hard to put together this conference, the sponsors, the presenters, the speakers, I want to thank you all for attending live or attending virtually. We look forward to welcoming you in Arizona for the annual conference, but in the meantime, please go to the TEI website and seek out all the education and training opportunities that are available, and certainly provide your feedback on things that we can do better, things that we can continue to do, and things that we should do. Thank you all for coming. This concludes the Midyear Conference.