Public corporations, private equity-backed portfolio companies, and privately held companies often look to mergers and acquisitions (M&As) to drive growth and shareholder value.

However, pursuing M&A-driven growth may be complicated, since companies must comply with ever-evolving financial and tax reporting requirements, deal with increasing financial audit and tax authority scrutiny, and consider other regulatory and compliance elements. Independent valuation assessments can play a significant role in helping companies to identify the appropriate deal opportunity; negotiate, structure, and effectively close the deal; and comply with all deal-related financial and tax reporting requirements.

Identifying the appropriate valuation standard and methodology before performing the valuation is essential, since applying different standards may impact the results. Differences may arise between fair value (FV) established for financial reporting purposes and values derived from either of the two tax reporting standards, the fair market value (FMV) standard or the arm’s-length standard (ALS).

Sometimes a valuation may need to satisfy more than one standard. For instance, an FV analysis for financial reporting and an FMV analysis for tax reporting may be required for purchase price allocations in an acquisition, followed by an ALS valuation for transfer pricing purposes in a post-acquisition business reorganization. The three standards diverge at many points despite sharing similar principles and methods, such as the use of the income, market, and cost or asset approaches under FV and FMV, or the similarity of the relief-from-royalty and comparable uncontrolled transaction-based income methods under FMV and ALS.

Regardless of the standard used, companies may need to consider multiple factors for each valuation standard before establishing a value. This article will highlight some relevant valuation considerations from US financial and tax reporting perspectives concerning three common issues that arise in M&A transactions: purchase price allocations, Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 382 limitation calculations, and tax receivable agreements.

In addition to the generic considerations highlighted below, each valuation needs to consider many additional nuances, depending on the specific facts and circumstances of the transaction. It may be helpful to consult with a valuation professional to ensure that the valuations satisfy the requirements under each standard and withstand financial audit and tax authority scrutiny.

Purchase Price Allocations

In M&A transactions, a purchase price allocation (PPA) may be required to allocate the purchase price into certain asset categories of the acquired entity. This section provides an overview of some key differences between purchase price allocations for US financial and tax reporting purposes, including the underlying rules, the relevant valuation standards, and the treatment of contingent consideration, transaction and restructuring costs, deferred taxes, and accrued liabilities.

Underlying Rules

For US financial reporting, Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 805 of the Financial Accounting Standards Board covers accounting and financial reporting requirements for:

- business combinations; and

- acquisitions of assets or groups of assets that do not meet the definition of a business.

Whether the acquired assets meet the definition of a business under ASC 805 can affect the purchase price allocation framework.

In a business acquisition, the fair value of total purchase consideration is allocated to the various assets of the business on an FV basis, including net working capital, fixed assets, other net assets, and identifiable intangible assets, with the residual allocated to goodwill. In a business combination, the FV of total purchase consideration should include any contingent consideration (e.g., earnout) and exclude any buyer-specific transaction expenses.1

If the acquired assets do not meet the definition of a business under ASC 805, the total purchase cost is allocated to the acquired assets on a relative FV basis, with no resulting goodwill. The purchase cost in the acquisition of assets not meeting the definition of a business can include certain transaction expenses and exclude any contingent consideration.2

In either case, intangible assets should be disaggregated and valued separately if they meet recognition criteria, that is, they arise from contractual or legal rights or they are separable from the entity on their own or in combination with other related assets or liabilities. Primary categories of intangible assets under ASC 805 include:

- marketing-related assets;

- customer-related assets;

- artistic-related assets;

- contract-based assets; and

- technology-based assets.3

For US tax reporting, both the acquirer and the seller must perform a purchase price allocation and file Form 8594 (Asset Acquisition Statement Under Section 1060) when there is a transfer of a group of assets that make up a trade or business and the acquirer’s basis in these assets is determined wholly by the amount paid for them.4

Under IRC Section 1060, the purchase price of an entity must be allocated to the assets under the residual method.5 The purchase price is allocated, in order, to each of the following asset classes (each with examples of asset types within it):

- Class I: cash and cash equivalents;

- Class II: actively traded personal property, certificates of deposit, and foreign currency;

- Class III: accounts receivable, mortgages, and credit card receivables;

- Class IV: inventory;

- Class V: all assets not in classes I–IV, VI, and VII (equipment, land, buildings);

- Class VI: IRC Section 197 intangibles, except goodwill and going concern; and

- Class VII: goodwill and going concern.6

Valuation Standards

Another difference in purchase price allocations performed for US tax versus financial reporting purposes lies in the appropriate standard of value that needs to be applied.

Fair Value Standard

The FV standard described in ASC 820 applies for US financial reporting purposes. According to ASC 820, fair value is the price received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.7

ASC 820 emphasizes that FV is a market-based measurement, not an entity-specific one. Management’s intended use of an asset or planned method of settling a liability is irrelevant when measuring fair value. Instead, determining the FV of an asset or liability relies on a hypothetical transaction at the measurement date, considered from the perspective of a market participant.8

ASC 820 establishes an FV framework applicable to all FV measurements. Under ASC 820, fair value is measured based on an exit price (not the transaction or entry price) determined using several key concepts, including market participants, the unit of account, the principal (or most advantageous) market, the highest and best use for nonfinancial assets, and the FV hierarchy.9

Fair Market Value Standard

The FMV standard described in Internal Revenue Ruling 59-60 applies for US tax reporting purposes. FMV is the price at which the property would change hands between a willing seller and a willing buyer when the seller is under no compulsion to sell and the buyer is under no compulsion to buy, with both parties having reasonable knowledge of relevant facts.10

Contingent Consideration

Another important difference between financial and tax reporting purchase price allocations is the treatment of contingent considerations.

For US financial reporting, contingent consideration is measured at FV if the acquired assets meet the definition of a business under ASC 805, and it is recognized at the acquisition date as part of the purchase consideration.11

For US tax reporting, contingent consideration is generally not recognized until the contingency is resolved. Depending on the deal’s structure, contingent consideration may be treated as part of the purchase price or compensation to the seller for services rendered.12

Transaction and Restructuring Costs

In addition, the FV and the FMV standards differ in their treatment of transaction costs and restructuring costs.

For US financial reporting, if the acquired assets meet the definition of a business under ASC 805, the purchase price allocation excludes buyer-specific transaction costs.13

For US tax reporting, the treatment of transaction and restructuring costs depends on the nature of costs. Certain costs are deductible as expenses, whereas others are capitalized.14

Deferred Taxes and Accrued Liabilities

Finally, the two standards also treat deferred taxes and accrued liabilities differently.

For US financial reporting, deferred taxes and accrued liabilities (assuming they will exist post-closing) are included in the purchase price allocation.15

For US tax reporting, deferred taxes are excluded, and the treatment of accrued liabilities depends on the facts and circumstances of the transaction evaluated through various tests such as the all-events test and the economic performance rule outlined in IRC Section 461.

Valuation Requirements

Given these differences, it is important to coordinate the FV and FMV analyses to ensure consistency in the two valuations and to reconcile any differences between the two standards. Coordination is especially important in cases where a company is considering asset transfers as part of a post-deal reorganization, because there are additional differences between the FMV standard used for generic tax purposes and the ALS applied in transfer pricing.

IRC Section 382 Limitations

IRC Section 382 limitations often pose critical challenges in M&A transactions. When a company changes ownership in an M&A transaction, Section 382 limits certain tax attributes.

Specifically, it limits the incremental value a corporation may achieve from harvesting historical net operating losses and other tax credits in an ownership change.16

According to Section 382, an ownership change occurs when ownership by one or more shareholders with a five percent interest in the company increases by more than fifty percent over the lowest percentage of stock owned by these shareholders at any time during the testing period, generally three years before the ownership change.

The extent of the Section 382 limitation depends on, among other things, the FMV of the equity immediately before the ownership change, the applicable federal tax-exempt interest rate, and the amount of the net unrealized built-in gain or loss at that time.

Valuation Requirements

A valuation may be required to establish:

- the FMV of the equity immediately before the ownership change; and

- the FMV of the assets to determine the net unrealized built-in gain or loss immediately before the ownership change.

As with purchase price allocations, tax teams may need to coordinate with financial reporting teams to ensure that the FMV valuations conducted when calculating the Section 382 limitation are reconciled with any FV analyses performed for US financial reporting purposes associated with the transaction.

Tax Receivable Agreements

Another common issue in M&A transactions is tax receivable agreements (TRAs). TRAs may be used in M&A transactions to compensate the seller for any valuable tax attributes, such as basis step-ups or net operating losses created during the deal. TRAs may also be used in initial public offerings (IPOs) via the creation of an umbrella partnership C corporation (Up-C structure) to compensate the pre-IPO equity owners for the tax attributes resulting from reducing the post-IPO business’ tax liability.

Valuation Requirements

As with purchase price allocations, it is important to coordinate any valuations conducted under the different valuation standards. For example, a valuation may be required under the FV standard, because corporations are required to record a liability in their financial statements for the probable amount of future TRA payments. A valuation under the FMV standard may be required in a post-IPO buyout of the TRA by the corporation from the pre-IPO equity owners.

Valuation Approaches

This section highlights three valuation approaches in the context of PPAs, Section 382 limitation calculations, and TRAs. As noted earlier, the FV and FMV standards differ, but the primary valuation approaches are broadly consistent across the two standards.

For this reason, this section will cover the primary approaches and methodologies jointly. ALS methods are outside the scope of this article, since they are not directly relevant to PPAs, Section 382 limitation calculations, and TRAs.

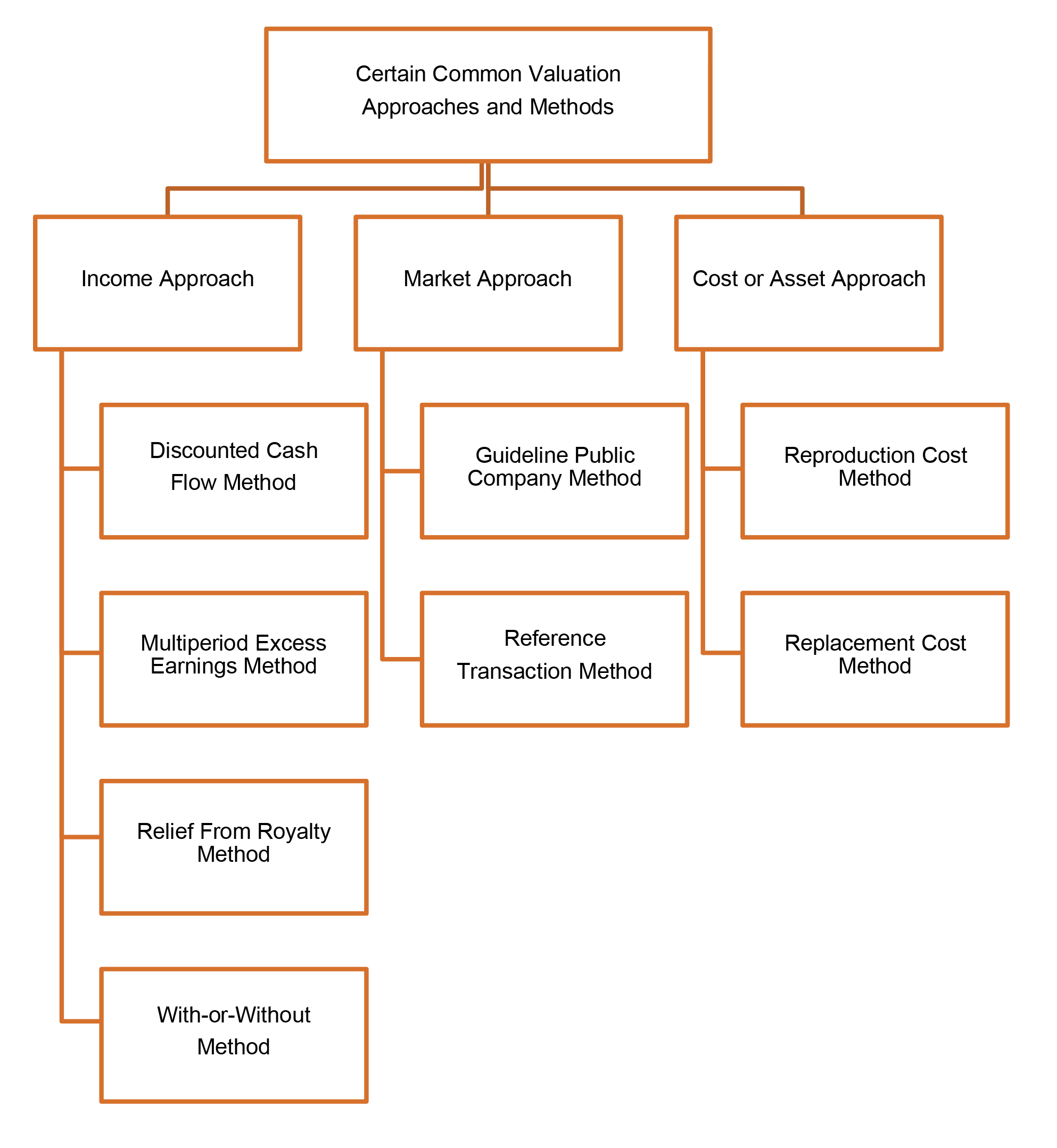

The figure below summarizes the three main valuation approaches under the FV and FMV standards: the income approach, the market approach, and the cost or asset approach.17

Income Approach

The income approach measures the value of a business or other asset based on the stream of benefits or cash flows expected to arise from it. The income approach derives value by forecasting cash flows or earnings in each year, calculating a terminal value if applicable, and discounting the cash flows to the present value at an appropriate discount rate.

The discount rate typically considers the time value of money, the risk inherent in the cash flow stream, and current rates of return on capital. The greater the perceived risk in the forecasted cash flows, the higher the discount rate and the lower the present value of the cash flows from the business or asset.

The income approach applies specific methods or techniques, in addition to a standard discounted cash flow method, to different assets, depending on the facts and circumstances of the transaction and the characteristics of the asset under valuation.

These methods include the multi-period excess earnings method, the relief from royalty method, and the with-or-without method. Other less common methods under the income approach are the cost-savings method and the greenfield method, which are beyond the scope of this article.

Under these methods, quantifying the appropriate cash flow streams, estimating an appropriate economic life, and developing an appropriate discount rate are important steps in establishing a reliable value.

Discounted Cash Flow Method

The first common method under the income approach is the discounted cash flow (DCF) method, which projects all expected future economic benefits (such as net cash flow or some other earnings variable) and discounts each expected benefit back to present value at an appropriate discount rate.

The forecast period, typically five to ten years, should be long enough to capture all anticipated variations in the company’s return until a stabilized return is achieved. The terminal period reflects a normalized level of earnings or cash flows used to calculate a value for all years after the forecast period.

Typically applied to establish business enterprise and corresponding equity values, this method is often useful in Section 382 limitation calculations to determine the FMV of an equity immediately before the ownership change.

Multi-Period Excess Earnings Method

The multi-period excess earnings method (MPEEM) is often used to determine the FV and FMV of intangible assets in purchase price allocations and to determine the FMV of intangible assets in Section 382 limitation calculations.

This method establishes the value of intangible assets based on excess earnings attributable to them. The method is based on the premise that a stream of cash flows can be reliably identified for an asset portfolio that contains certain intangible and other supporting assets. By determining appropriate returns for the supporting assets through contributory asset charges (CACs), a residual stream of excess income is established and allocated to the specific intangible asset.

Similar to the DCF method, the residual excess income stream is then discounted back to present value through an appropriate discount rate.

Relief From Royalty Method

The relief from royalty method (RFRM) is often applied to determine the FV and FMV of intangible assets in purchase price allocations and the FMV of intangible assets in Section 382 limitation calculations.

This method establishes the FMV of intangible assets based on hypothetical royalty payments that would be saved by owning the intangible assets instead of licensing them from a third party.

Similar to the DCF and MPEEM methods, once the RFRM establishes the royalty stream of the intangible assets, they are discounted back to present value using an appropriate discount rate.

With-or-Without Method

The with-or-without method (WWM) determines the value of an asset based on the assumption that without it, a business enterprise would suffer a loss of income or an incremental cost.

TRAs are typically valued through the with-and-without method. The valuation compares the actual tax liability of the company with the TRA tax assets to its hypothetical tax liability without them. The excess of the hypothetical tax liability over the actual tax liability for each year establishes the tax attributes under the TRA.

As with the other methods the income approach employs, the FMV of the tax assets under the TRA is based on the present value of those tax attributes discounted through an appropriate discount rate.

Market Approach

The market approach establishes the value of assets or businesses based on market values of similar assets or businesses sold under similar conditions. The market approach is based on the premise that an asset or a business can be valued relative to comparable transactions of assets, businesses, or interests in those businesses.

Therefore, this approach is often applied in Section 382 limitation calculations to determine an appropriate value for a business enterprise and corresponding equity value immediately before an ownership change. Since certain types of intangible assets rarely transact individually, this approach may apply only in limited circumstances to certain types of assets, such as intangible assets.

The primary methods under the market approach for valuing a company, business, or ownership interest appear below.

Guideline Public Company Method

The guideline public company (GPC) method establishes the value of a business based on market prices realized in comparable transactions. The technique entails undertaking an appropriate market analysis of publicly traded companies that are reasonably comparable to the relative investment characteristics of the relevant business.

The GPC method calls for choosing valuation ratios that relate market prices to selected financial statistics derived from the guideline public companies and then applying them to the company or business after any adjustments for financial position, growth, markets, profitability, and other factors.

Reference Transaction Method

The reference transaction (RT) method establishes value based on market prices realized in comparable transactions. This method derives indications of value based on the prices at which entire businesses have been sold. There must be a reasonable basis to select certain transactions for comparison.

Cost or Asset Approach

The cost or asset approach estimates an asset’s value based on the cost to reproduce or replace it. The method of determining the cost to reproduce or replace an asset may vary greatly depending on the specifics.

Typically used to value tangible assets, this approach is often applied in purchase price allocations or Section 382 limitation calculations to establish the FV and FMV of certain fixed assets.

Conclusion

This article discusses several relevant valuation considerations from US financial and tax reporting perspectives in relation to three common issues arising in M&A transactions: purchase price allocations (PPAs), IRC Section 382 limitation calculations, and tax receivable agreements (TRAs).

Beyond these generic considerations, valuations must take into account the nuances inherent in the facts and circumstances of every transaction. Given the complexity of mergers and acquisitions and the number of valuation standards that businesses may need to contemplate using, it is important to pay close attention to all relevant financial reporting and tax valuation considerations during the valuation process. Appropriate coordination between the FV and FMV analyses may help companies avoid inconsistencies between them and thus may mitigate controversy upon audit.

Tom K. Gottfried and Charles Sapnas are managing directors at Valuation Research Corporation.

Editor’s note. This article is provided solely for educational purposes; it does not take into account any specific individual’s or entity’s facts and circumstances. It is not intended, and should not be relied upon, as tax, accounting, or legal advice. Valuation Research Corporation expressly disclaims any liability in connection with the use of this article or its contents by any third party.

Endnotes

- Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) ASC 805-30-30-7.

- FASB ASC 805-50-30-1 through 805-50-30-3.

- FASB ASC 805-20-55-13.

- Internal Revenue Service instructions for Form 8594.

- IRC Section 1060 and IRC Section 338(b)(5).

- IRC Section 1060.

- FASB ASC 820-10-35-2.

- FASB ASC 820-10-35-9.

- FASB ASC 820-10-35.

- IRS Revenue Ruling 59-60.

- FASB ASC 805-30-30-7.

- IRC Sections 263 and 461.

- FASB ASC 805-30-30-7.

- IRC Section 263.

- FASB ASC 805-20-25-1.

- IRC Section 382, Limitation on Net Operating Loss Carryforwards and Certain Built-in Losses Following Ownership Change.

- See FASB ASC 820-10-35 and IRS Internal Revenue Manual Sections 4.48.3 through 4.48.6, which are the sources for the remainder of this section on the three valuation approaches under the FV and FMV standards.