In 2015, the vast majority of U.S. international companies have many markets to choose from, including China, India, Japan, Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Africa, and Canada. Increasingly, however, global firms are looking to market their products, invest in economies, engage in trade, or simply do business with countries in Latin America.

And if corporations are doing business in Latin America, as sure as the sun comes up tomorrow, there will be tax issues.

By any measurement, Latin America, with a population of more than 600 million, is a key trade area for U.S.–based companies. U.S. producers export three times as many products to Latin America than to China. On the other side of the trade equation, Central and South America (excluding Mexico) purchase fifty percent more goods from the United States than China.

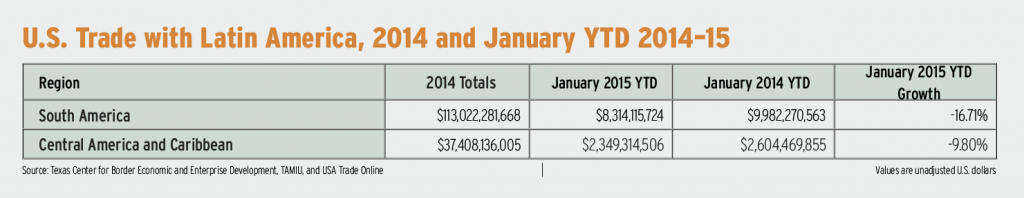

Latin America, including Mexico, accounts for between twenty and twenty-five percent of total U.S. trade—imports plus exports. In addition, about twenty percent of foreign direct investment in the region comes from the United States. Exports from South and Central America totaled about $169 billion in 2013. At the same time, imports from Latin America were about $146 billion (see graphic, U.S. Trade with Latin America).

Mexico and Brazil — and Colombia

Who’s leading the way in Latin America? Mexico and Brazil are the chief economic powers in terms of GDP, according to most experts. The most important countries in terms of doing business in Latin America are Brazil, due to its burgeoning population (more than 200 million), growing middle class, and continental size; Mexico, due to its border with the United States and role in NAFTA; and Colombia, due to its economic development and expanding economy, according to Lionel Nobre, Latin America tax director at Dell and TEI Latin American founding member.

Paulo Sehn, partner at Trench, Rossi in São Paulo, Brazil, agrees that Colombia’s importance is on the rise: “Colombia has been increasing its visibility in the region as a result of a stronger economic environment and important reforms, which is also the case for Peru. Meanwhile, Argentina continues to face enormous challenges since the default on its external debt and the somehow excessively regulated internal market that does not foster foreign investments,” he says.

“Cuba is another jurisdiction that will have to be covered by tax professionals, as is the case in other Central American and Caribbean islands, once the country starts to embrace capitalism and adopts a more Western economy and tax system.”—Lionel Nobre

In addition, Sehn says, Chile is an important country in the region for its economic and political stability and for showing the highest integration with the international markets in the Latin America region, while Venezuela continues to face enormous economic and political challenges, as operating under the current business environment is quite hostile to foreign investments.

Mexico’s proximity to the United States is a major factor in trade relations between the two nations, say Sehn and Nobre. Mexico’s shift toward allowing a private sector role in the petroleum sector, which has long been controlled by the government, has been attributed to shale-oil discoveries and improvements in fracking technology in the United States, which has led the way in revitalized trade with our neighbor to the south.

In fact, Latin America as a whole has been the largest foreign supplier of oil to the United States and a key partner in the development of alternative fuels, which has helped make the region our fastest-growing trading partner.

How much free trade is going on among Mexico, Brazil, and the United States? In the significant automobile market, Brazil and Mexico renewed vehicle quotas for four years in March, delaying the implementation of a free trade agreement between the two countries.

The region’s two largest economies were scheduled to have free trade in vehicles beginning March 19, and the Mexican government worked for that result. However, Brazil sought a delay, and Mexico agreed.

The countries had allowed free trade in vehicles from mid-2011 to early 2012 but changed to a quota system after Brazil complained that the strengthening of the Brazilian currency over the previous decade made its cars uncompetitive abroad. Under the new agreement, Brazil and Mexico will permit $1.56 billion of duty-free vehicle imports for the first year of the agreement, increasing three percent annually until the agreement expires in 2019, when two countries return to a free trade regime.

The impetus for increasing trade with Latin America and making it a market destination for growing global organizations starts with the top officials in the executive branch. In 2014, U.S. Secretary of Commerce Penny Pritzker announced the “Look South” initiative targeted at increasing business with trade partners in Latin America. Look South encourages U.S. companies to do business with Mexico and the U.S.’s ten other free trade agreement partners in Central and South America.

Pritzker specifically pointed to untapped business opportunities south of Mexico, which the program hopes to open up for U.S. companies. But she stressed that U.S. businesses need to take advantage of the free trade agreements and reported that only one percent of U.S. businesses currently export their products, and of those, fifty-eight percent export to only one country, usually Mexico or Canada. While the typical business that sells to just one market generates roughly $375,000 in export sales, companies with two to four export markets have average export sales of $1 million; those that export to five to nine markets average $3 million in sales.

Agricultural commodities exports from Latin America have increased significantly together with the import of finished goods and services, notes Nobre.

In terms of developing the Latin American market, the sky’s the limit, according to many global business and economic experts. Economic growth projections for the target countries in the initiative range from four percent in Colombia to seven percent in Panama.

The U.S. Department of Commerce wants to tap into that growth to benefit U.S. businesses. More than half of all the free trade agreements negotiated by the United States are in Latin America, including Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Peru. Tariffs are low, if they exist at all, which makes those markets fertile ground for more U.S. exports, and many of the countries are adopting good trade practices and standards in a variety of areas, the Department of Commerce reports.

Asian Investment

Latin America also has become an expanding regional market for Asian industrial goods and foreign direct investment. Trade between the two regions has more than doubled over the past decade, reaching a historic high of more than $500 billion dollars in 2014—an amount expected to grow to at least $750 billion by 2020.

Exports to South and Central America totaled about $169 billion in 2013. At the same time, imports from Latin America were about $146 billion in 2013.

Latin America Tax Issues

“Latin America has very complex and always-changing tax systems with increasing foreign investment, which provides major opportunities for tax professionals in this region,” asserts Nobre. The main tax issues in Latin America today concern indirect taxes, which are assessed on the taxpayer generating profit, and electronic tax and accounting systems.

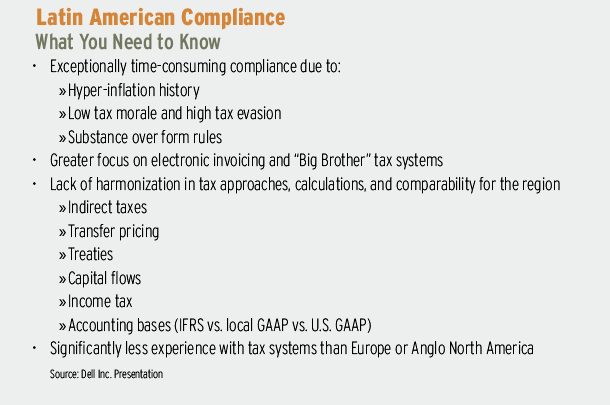

Compliance in Latin America, Nobre says, is exceptionally time-consuming due to three main factors: history of hyperinflation; low tax morale and high tax evasion; and “form over substance” rules. In addition, the region lacks harmonization in tax approaches, calculations, and comparability on a variety of issues, including indirect taxes, transfer pricing, treaties, capital flows, income tax, and accounting bases (see graphic, Latin American Tax Compliance).

In addition, notes Nobre, the region has a variety of tax audit trends. For example, Mexico focuses on cross-border transactions and base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) guidelines.

Finally, Nobre says, it is important to point out that due to the adversarial relationship taxpayers have with the tax authorities and the form over substance rules in the region, it is very common for taxpayers to litigate tax matters in court, including in front of the supreme courts in the various countries of the region.

“The future in-house tax professional in Latin America will not only need accounting but also informatics and systems skills to be a truly successful in-house tax professional.”—Lionel Nobre

The Transcendence of Brazil

For example, Nobre notes, in Brazil more than twenty-five percent of the cases argued in front of the supreme court are tax-related. “These can be very cumbersome processes, often lasting several years or even decades, requiring that in-house professionals be strong litigators as well as content experts,” says Nobre.

Sehn echoes Nobre’s sentiments: “Tax disputes in Brazil are quite challenging because of the extended time length of the cases, which can take as long as fifteen to twenty years to be resolved if both the administrative and judicial paths are subsequently taken, and the complex tax environment with lots of tax rules that are quite frequently modified and thus require a continued follow-up of the legislation and of the case law from the Brazilian courts,” he says.

In addition to being an economic bellwether for the region, Brazil also is an extremely important country in terms of tax issues and processes. Brazil has a convoluted tax system with more than fifty different kinds of taxes at the municipal, state, and federal levels, which Nobre says are based on an outdated tax code that exists in concert with one of the most efficient electronic tax systems in the world. “In Brazil, there are income taxes, gross receipt taxes, several kinds of indirect value-added taxes, plus numerous social contributions, financial transaction taxes, and a very complex customs system,” he says.

“Tax disputes in Brazil are quite challenging because of the extended time length of the cases, which can take as long as fifteen to twenty years to be resolved.”—Paulo Sehn

Brazil requires not only dealing with the tax burden (income tax plays a small part, but the indirect tax burden is more significant) but also coping with the compliance responsibility, which is all electronic. Companies and individuals are required to file all their taxes and supporting data (which, for companies, includes accounting records, invoicing, and payroll) on a real-time basis with the tax authorities, which then cross-reference this information with returns filed to make sure they match. This “Big Brother tax system,” as it is known, has provided the Brazilian tax authorities with a very efficient tax system and has raised tax revenue ten-fold over the last ten years, according to Nobre.

Brazil also has a very low threshold for errors, which cannot be fixed at the back end for tax-compliance purposes (see graphic, Brazil Regulation of Tax Environment).

One of the interesting cases that Nobre is currently working on concerns Brazilian transfer pricing that is “very unique and not compliant with OECD models, which creates very interesting challenges for multinational companies.”

Brazil is now facing an important shift in its accounting rules with the enactment of Law No. 12,973/14, which ends the Transitory Tax Regime, Sehn says. Beginning this year, Brazilian companies have to fully adopt the International Financial Reporting System (IFRS) without eliminating such effects on the determination of the corporate income tax.

Sehn breaks down the major corporate and personal tax issues in the other Latin American countries:

Chile: The country has been undergoing major tax reform since September 2014, with the goals of increasing tax collections by 3.02 percent of GDP and providing additional and permanent tax revenues to finance additional, permanent expenditure in education. The plan is designed to achieve those objectives through new taxable events, the increase of current tax rates, and the enlargement of taxable bases, plus the elimination of tax deferral and tax savings mechanisms.

Colombia: The country has just created a wealth tax to be levied on Colombian and foreign individuals who are not tax residents with wealth in the country directly or through permanent establishments (PEs) (double taxation treaty exceptions apply). It also has increased its global corporate income tax for resident and nonresident companies.

Peru: This jurisdiction is setting new income tax rates, which were at thirty percent until 2014 and will be reduced to twenty-eight percent for 2015–16, to twenty-seven percent for 2017–18, and to twenty-six percent starting in 2019. But the corporate income tax rate for nondomiciled entities remains at the thirty percent level.

Mexico: The neighbor to the south has promulgated new legal provisions addressing BEPS issues, such as disallowing deductions for cross border–related party payments on royalties, technical assistance, and interest made to a foreign entity that controls or is controlled by the Mexican entity (i.e., effective control over the other or administered to the extent that it may decide the moment of profits distribution), if certain conditions are not met. New domestic requirements have been established to access treaty benefits as, for example, the submission of a new informative return by the Mexican taxpayer (making payments abroad and applying reduced rates or other treaty benefits) that (1) discloses fiscal status and (2) informs of any cross-border payments.

Venezuela: This oil-rich country has increased the statute of limitations from six to ten years (previously four to six years) and established that penalties for committing tax fraud, fraudulent insolvency for tax purposes, and failing to pay withheld amounts are no longer subject to the statute of limitations.

“The ever-changing legal scenario poses a continued challenge to the tax professionals operating in the region and, accordingly, great opportunities for skilled tax lawyers.” —Paulo Sehn

Then, of course, there’s the question of what is going to happen in Cuba in terms of tax issues now that the Obama administration has started an initiative to increase cultural exchanges with the country that is only ninety miles from Florida. “Cuba is another jurisdiction that will have to be covered by tax professionals, as is the case in other Central American and Caribbean islands, once the country starts to embrace capitalism and adopts a more Western economy and tax system,” says Nobre.

TEI’s Latin America Chapter

The TEI Latin America chapter was launched to meet the needs of in-house tax professionals in the region who want to voice their concerns to their peers and organize themselves to further strengthen the in-house tax profession, Nobre says.

“Notwithstanding the fact that tax can make or break a business in Latin America and that in-house tax professionals have been practicing in the region for at least the last fifty years, these professionals organizationally have always been a part of another department, such as finance, accounting, and controllership, and not an autonomous department as is the case more today,” says Nobre. In the past, in-house tax professionals were part of the accounting teams or general finance teams; however, with the increased complexity of the tax area, a need for more specialized professionals—with legal skills, for example—has simultaneously developed. What we now see are professionals who have the accounting, legal, treasury, finance, business, and IT skills to adequately calculate, file, and manage companies’ taxes in the region, he explains. The TEI chapter will help unite these professionals with like–kind challenges, provide a platform for the exchange of ideas, and strengthen the in-house tax profession in the region.

The chapter plans on having regular meetings and social events to foster a sense of unity among the in-house tax professionals in the region. Nobre says the chapter also will help develop successful in-house tax professionals who have the skills to meet the tax environment of the future. Tax professionals not only need to understand the tax and legal system (and ideally have an accounting or law degree), but they absolutely need to understand their companies’ businesses and be experts in systems and processes, asserts Nobre. “I am a so-called 1.0-generation tax professional with a law degree and accounting skills, but the future in-house tax professional in Latin America will not only need accounting but also informatics and systems skills to be a truly successful in-house tax professional,” Nobre says.

The Future

The increasing chain of commerce between Latin American companies and the rest of the world, coupled with the complex tax environment in the region, is certainly a good indication that opportunities for tax professionals will continue to expand in Latin American and that those specializing in the region’s tax systems will find companies are and always will be seeking professionals who can tackle those tax issues, says Sehn. “The ever-changing legal scenario poses a continued challenge to the tax professionals operating in the region and, accordingly, great opportunities for skilled tax lawyers,” concludes Sehn.

Michael Levin-Epstein is senior editor of Tax Executive.