The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), which comprises the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, and Kuwait, has decided that its member countries will implement a value-added tax (VAT) system by 2018.

This decision was adopted in the context of a dramatic drop in recent years in the oil revenues that finance most of these countries’ public expenditures.

The news of the forthcoming introduction of a five percent VAT in the Gulf region has plunged the VAT world into turmoil.

The GCC has enacted the Unified GCC VAT Framework Agreement (GCC VAT framework) that lays the groundwork for its members to implement VAT in their respective jurisdictions.

At press time, only two GCC members, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), passed legislation to implement the GCC VAT system in their respective countries. The other four member states will more likely than not postpone the introduction of the VAT system until mid-2018 or later.

The main purpose of a VAT system is to impose a broad-based tax on final consumption by households to avoid burdening businesses.

It is noteworthy that VAT will be imposed not only on most domestic supplies of goods and services across each GCC country but also on purchases made from unestablished suppliers, which currently are untaxed. These purchases will now be taxable through the so-called reverse-charge mechanism.

The VAT is collected in stages. Each business in the supply chain collects the tax and remits a portion of it based on its margin, which is the difference between the VATs on inputs and outputs.

Businesses have a relief mechanism to offset the VAT, the invoice credit method, whereby each business credits the input tax against the output VAT charged on its supplies, and the business either sends the balance to the tax authorities or receives a refund when it has excess credits.

The right to deduct the input VAT in each phase of the process, except in the final stage of selling to the end consumer, guarantees the neutrality of this tax and prevents the cascading effects of other indirect taxes.

The place of taxation follows the physical location where the goods are supplied.

EU VAT Vs. GCC VAT

Some describe the GCC’s VAT as a simplified version of the European Union’s VAT system and, to a certain extent, they are right.

That doesn’t mean the two systems are twins. There are fundamental differences between the EU VAT directive and the GCC VAT framework with regard to, for example, the taxable base, place-of-supply rules, and rates. These distinctions should draw the attention of any company considering adapting its ERP systems and processes to apply GCC VAT.

Taxable Base

With regard to the taxable base, the EU VAT has embraced the “subjective value” for VAT purposes. The basis for assessing VAT, as expressed in several judgments by the Court of Justice of the European Union (ECJ), “is the consideration actually received and not a value estimated according to objective criteria.”

Corporate tax experts might find it shocking that VAT upholds the “subjective value” rather than the arm’s-length principle espoused in the world of transfer pricing. However, as an exception, the open market value should be applied in the case of supplies between related parties where the subjective value could be manipulated to grant unfair advantages.

In contrast, the GCC VAT framework has opted for the arm’s-length principle even in unrelated transactions, as follows: “The fair market value is an amount for which the goods and services can be traded in an open market between two independent parties under competitive conditions prescribed by each Member State” (Article 26).

The introduction of “objective value” as the basis to determine the taxable base raises questions about the freedom to set prices between parties (related or not) and introduces a high degree of legal uncertainty regarding the consideration agreed to by the parties and in the price range(s) used by tax authorities. If the scope of the rule is not sufficiently narrowed by member countries, the potential risks linked to abandoning the subjective valuation would be innumerable.

Nevertheless, some may argue that the main hurdle does not lie in the freedom to set prices but in having to include another field, one that includes the market value, in each invoice, to calculate the VAT on a higher (or lower) amount than the contract price. When trading on the commodity market, where prices fluctuate daily, traders might have an agreement on delivery of goods against a set price for a longer period, in which case there will be a discrepancy between the amount effectively charged and the base used to calculate the VAT.

To be safe, should traders always overcharge VAT (better more than less), or would doing so create risk on the deduction side? This issue poses questions about legal certainty and even the proper functioning of the system.

So far, fortunately, KSA’s regulations have limited the wide limits of the fair market value to when the consideration agreed between related parties is lower than arm’s length and benefits the acquirer with limited right to reclaim the VAT. Whether other member states will follow KSA’s steps is for now unknown.

Rates

What also seems unusual in the GCC VAT framework is that all prices must be VAT-inclusive (Article 25(2)), without clarifying whether this applies to both B2B and B2C or only to B2C supplies. If GCC member countries take the view that even in B2B transactions the pricing should be VAT-inclusive, that may create difficulties in the event of rate changes when suppliers are not entitled to adjust pricing accordingly to pass on VAT rate increases (or decreases) to business customers. In anticipation, companies should refresh the tax clauses of their ongoing contracts to set VAT-exclusive pricing.

The GCC VAT framework also differs from the EU VAT system with respect to VAT rates. The situation in the European Union is rather chaotic, with diverse and very high standard rates (up to twenty-seven percent) and a myriad of various reduced rates altogether creating controversy and even incentivizing fraud.

In contrast, GCC member countries will start with a single VAT rate of five percent (Article 25), which is simpler and offers the advantages of a level playing field for taxable persons and tax authorities in terms of tax compliance. Moreover, food, medicine, and medical equipment would become eligible for a zero VAT rate, which individual member countries would not have the discretion to change.

It is expected that the incentives to commit fraud or to operate in the informal market might be significantly reduced, given that a lower rate is likely to increase compliance.

Place-of-Supply Rules

Another important aspect is the use of proxies for place-of-supply rules.

According to the OECD VAT guidelines, these rules facilitate the ultimate objective of the tax, which is to tax the final consumption.

By default, the GCC VAT framework mirrors the EU and OECD VAT rules, embracing the destination principle for B2B supplies. The destination principle applied to cross-border supplies of goods is certainly achievable through customs border controls, although, as already experienced in the EU internal market when such controls are gone, taxing the supplies becomes fairly complicated. The GCC is going to experience similar troubles, because its intra-GCC supplies of goods will replicate the regime for taxing intra-EU deliveries of products. Detecting the place of consumption of services and other intangibles is a completely different story, because services do not leave a trace of their supply.

Supplies of goods

The place of taxation follows the physical location where the goods are supplied. Therefore the rule relies not only on the nature of the goods delivered but also on the way the supply is made. Goods that are not transported are taxable at the location where they are made available as a supply. The GCC VAT framework specifies that this must be the place where the goods are put at the disposal of the customer, encapsulating a reference to the economic transfer of the right to act as owner implicit in the concept of “supplies of goods.”

In contrast, goods transported or dispatched are taxed at the point where the goods were located once the transport began. On the contrary intra-GCC and intra-EU supplies of goods from one member state to another are taxed where the transport ends, leading to zero-rate the supply in the country of departure and tax the acquisition in the ship-to destination, as long as the supply is made to a taxable person registered in either in the ship-to state or in another state within the GCC or the EU.

In addition, for e-commerce sales to end customers the place of supply is set as the location where the customer receives the products, provided the seller has exceeded a given threshold in the relevant EU member state.

There is another subset of supplies which by including installation or assembly services are deemed to be taxed where the goods are configured and put to work.

Because the GCC derives most of its GDP from oil and gas, the POS rules in this region are extremely important. The taxing rights are transferred to the state where the taxable dealer buying the commodity through a pipeline is established. On the contrary supplies to end customers get taxed at the place of consumption (e.g., at gasoline stations or at home).

Overall, there are no apparent differences between the GCC and EU VAT rules in this area, so many companies would export the tax settings and processes from the EU to the GCC in the blink of an eye.

That said, multinationals should not forget to design strict controls to verify and keep a record of their customers’ identities, not only when entering into agreements but also throughout the life of the contract, because most of these rules are contingent upon the status of the recipient of the supplies.

Supplies of Services

The destination principle on B2B services frees from VAT the exports of services and taxes the imports at the same rate as the domestic supplies through the so-called reverse charge mechanism, which as the OECD defines is a tax mechanism “that switches the liability to pay the tax from the supplier to the customer.”

The proxy for B2C services, on the other hand, by default taxes the services in the location where the supplier is established to levy VAT on the consumption.

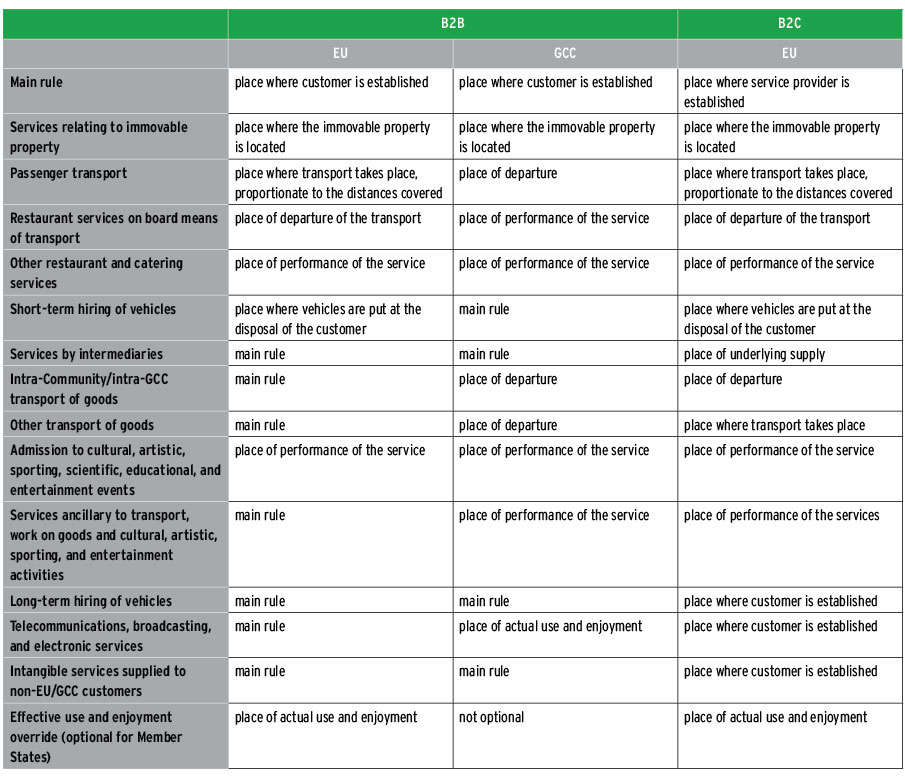

Nevertheless, there are some interesting differences between the EU and the GCC. (See table, page 86.)

One rule that creates more hurdles concerns the supply of electronic services and wire/wireless services, which are subject to VAT for both B2B and B2C at the place of actual use of the benefit from these services, “regardless of the place of contract or payment” as the UAE VAT Law outlines.

Unfortunately, the GCC VAT framework fails to include a list of the services included under these categories, in contrast with the EU VAT directive and implementing regulation, which provide what are considered to be e-services (although it is not an exhaustive list). Nevertheless KSA has substantially taken inspiration from the EU definitions of telecom and electronic services.

In addition to that, the definition of what “actual use” means leaves too much room for interpretation and could generate disputes between taxable persons and tax authorities.

Although the EU system has the “use and enjoyment” rules for e-services, the European Union has not significantly developed a definition of this concept, which could be a close concept to “actual use.”

In this context, multinational service providers would be wise to avoid signing centralized contracts of e-services when the services are provided in the GCC but are invoiced outside the GCC. Such contracts can indeed be marred by double taxation due to conflict between place-of-supply rules. On the one hand, the country where the services are delivered might tax those services based on the actual use of the service. On the other hand, the country where the bill is made, as long as the supplier and the customer are established there, can also decide to tax the services.

Time of Supply

VAT normally becomes due when the legal conditions necessary for VAT to become chargeable are fulfilled. However, there are instances when such taxable events do not automatically trigger the entitlement for the Tax authorities to claim the VAT from whoever is found liable to do remit the tax.

The GCC VAT framework does not draw a distinction between taxable events and chargeability, which is a distinction that is clearly made in the EU VAT Directive.

In practice, taxable events and chargeability are underlying concepts in the GCC VAT provisions, even if they are not expressly mentioned.

For instance, Article 23(3) of the framework deals with continuously supplied goods and services and provides that the VAT becomes due not when the services are performed but “at the earlier of either the date of payment stated in the invoice or the date of the actual payment.” It’s noteworthy that the taxable event on continuous supplies differs from that in place in the EU VAT Directive, whereby the last day of each of the billing periods to which the successive payments relate becomes the point of reference.

In order to fairly understand the sequence of events leading to the submission of the VAT to the authorities, we shall consider an example.

An IT company provides technical support services during September 2018. The taxable event is spread over that period. The chargeable event, however, occurs at the end of that period (September 30). The VAT becomes chargeable only after the invoice is raised within the time limits set forth by the local legislation (e.g., October 5). The VAT then is booked on October 5, 2018, for services provided during September and is remitted with the VAT return filed the month after.

Jurisdictional Oversight

The European Court of Justice has been critical to interpreting the hottest topics in the field of VAT. The ECJ steps in only at the request of national courts, which refer preliminary questions on the cases they are hearing to this high court.

The GCC did not envision the creation of a supreme court to oversee the correct interpretation of the VAT rules of the member states and to standardize the application of the tax in the GCC. Only the ministerial committee of the GCC has jurisdiction to consider matters related to the application and interpretation of the agreement with binding effects, but it is not by any means a judicial instance to appeal to object to decisions of the tax authorities.

Ultimately this omission can move the GCC away from constructing a common VAT system and may make things more difficulty for companies operating in the region.

Invoicing Requirements

At first glance, it seems that if KSA’s invoicing requirements became the standard for the rest of the GCC, they would differ little from those enforced in the EU.

The main difference, however, lies in the fact the EU VAT directive includes a numerus clausus for items that every invoice shall include, whereas the GCC VAT framework gives its member states more freedom.

But as the reader may notice from reading Article 53 of the KSA VAT regulations, the position of KSA toward enacting a general obligation to all the companies operating in this country to keep their records in Arabic and even issue the invoices in local language sounds too extreme for multinationals accustomed to operating in multiple locations with a common ERP system. The article reads as follows:

“The Tax Invoice must include the following details in Arabic, in addition to any other language also shown on the Tax Invoice as a translation:

- the date of issue;

- a sequential number which uniquely identifies the Invoice;

- the Tax Identification Number of the Supplier;

- in cases where the Customer is required to self-account for Tax on the supply, the Customer’s Tax Identification Number and a statement that the Customer must account for the Tax;

- the name and the address of the Supplier and of the Customer;

- the quantity and nature of the Goods supplied or the extent and nature of the services rendered;

- the date on which the Supply took place, where this differs from the date of issue of the Tax Invoice;

- the taxable amount per rate or exemption, the unit price exclusive of VAT and any discounts or rebates if they are not included in the unit prices;

- the rate of Tax applied;

- the amount of Tax payable, shown in riyals;

- in the case where Tax is not charged at the basic rate, a narration explaining the Tax treatment applied to the Supply;

- in cases where the margin scheme for Used Goods is applied, reference to the fact that VAT is charged on the margin on those Goods.”

A natural reaction to the requirement would be to upgrade ERPs to the latest versions or to install language patches to comply with it. Both, however, are easier in theory than in practice. Furthermore, records must be kept in Arabic—all records, including contracts, purchase orders, and any backups of transactions. These requirements call for a complete redesign of the processes in place to fulfill the language demands of the VAT regulations.

In this sense, the EU is far more liberal, in that it favors the freedom of parties to do business in the language they choose as long as they can, in case of an audit, translate the documentation into the local language as needed. Rumor has it that the UAE is heading in another direction, one that deemphasizes the importance of language.

Right to Deduct

The right to deduct is an integral part of the VAT system and fundamentally should not be limited.

To deduct VAT, a company’s purchases must have a direct, immediate connection with the output, and these expenditures must be part of the cost of producing the output.

What’s more, the taxable person must hold evidence of the receipt of the services and goods by means of a compliant invoice. Alternatively the KSA VAT implementing rules leave room to accept other commercial documentation “at the discretion of the authority.” Even if leaving things up to the authority’s best judgment is not necessarily ideal, at least KSA is considering the possibility historically embraced by the European Court of Justice to admit evidence beyond the invoice.

The EU has developed extensive case law that rests on the “substance over form” theory that benefits the taxable persons when authorities deny their right to deduct the VAT. The GCC, however, starts with a blank slate open to myriad interpretations that differ from member state to member state; these states would do well to take enormous advantage of this rich history of jurisprudence on the right to VAT deduction.

VAT Grouping

VAT grouping is optional both in the EU and the GCC member states. The main advantage of a VAT group is that intragroup transactions among entities that form part of the group are disregarded for VAT purposes.

The GCC framework doesn’t detail what conditions constitute a group, which means that member states can impose different entry requirements as they see fit.

For instance, KSA requires the grouped entities to remain “under common control.” In this sense, “common control” is defined as an entity that directly or indirectly controls over fifty percent of the capital or the voting rights of value of the legal person. Additionally, at least one of the legal persons must be a “taxable person,” which means that passive holding entities can join a group.

Import VAT Deferment

In line with some of the most advanced EU countries that enacted the import VAT deferment to the VAT returns so that VAT is simultaneously paid and deducted, so far KSA has recognized this possibility to traders that apply for it.

The cash flow benefits associated with this deferment are crucial, especially for traders that mainly import and export products or are just starting out.

Challenges Ahead

A Herculean task awaits businesses and tax authorities in the GCC region.

Setting the proper governance to tax transactions correctly and implementing tax calculation engines to automate tax compliance and minimize the likelihood of penalties will require highly skilled VAT professionals to be able to assist businesses as they prepare for the GCC VAT challenges awaiting them on January 1.

Companies should quickly develop a strategy to approach the implementation that includes the following points:

- understand the basics of VAT systems and how VAT affects each industry;

- apply for VAT registration in each GCC jurisdiction where the company operates;

- update business controls and audit trail processes to incorporate VAT guidelines;

- explore VAT-optimal supply chains and structures of legal entities;

- check existing contracts to find out which ones require proper VAT wording (e.g., not VAT-inclusive prices, etc.); and

- train accounts payable and accounts receivable teams about the importance of creating and processing fully compliant invoices to meet the extremely formalized requirements imposed by VAT legislation.

References

Annacondia, Fabiola (editor). EU VAT Compass 2017/2018. IBFD, 2017.

Echevarría Zubeldia, Gorka. “GCC: The New Kid on the VAT Block.” International VAT Monitor 28, no. 4 (2017). www.ibfd.org/IBFD-Products/Journal-Articles/International-VAT-Monitor/collections/ivm/html/ivm_2017_04_int_1.html.

Echevarría Zubeldia, Gorka. “Legal Uncertainty of the EU Effective-Use-and-Enjoyment Criterion.” International VAT Monitor 23, no. 4 (2012). www.ibfd.org/IBFD-Products/Journal-Articles/International-VAT-Monitor/collections/ivm/html/ivm_2012_04_e2_1.html.

Echevarría Zubeldia, Gorka. “First Step to a Worldwide VAT System: The OECD VAT Guidelines.” International VAT Monitor 25, no. 4 (2014). www.ibfd.org/IBFD-Products/Journal-Articles/International-VAT-Monitor/collections/ivm/html/ivm_2014_04_int_1.html.

Echevarría Zubeldia, Gorka. “The Second EU Invoicing Directive: A Missed Opportunity.” International VAT Monitor 21, no. 6 (2010). www.ibfd.org/IBFD-Products/Journal-Articles/International-VAT-Monitor/collections/ivm/html/ivm_2010_06_e2_4.html.

van Doesum, Ad, Herman Van Kesteren and Gert-Jan van Norden. Fundamentals of EU VAT Law. Wolters Kluwer, 2016.

Gorka Echevarría Zubeldia is the chairman of TEI’s European indirect tax committee.

Editor’s note: This article is an expanded version of the column “GCC: The New Kid on the VAT Block” (2017), published in International VAT Monitor 28, no. 4 (full citation under References).