One of our favorite clients, Gary, once told us a story as we began talking about a possible tax transformation project for the public company he had recently joined as its new vice president of tax.

Earlier in Gary’s career, he was the compliance tax manager for a large privately held corporation that sought to implement a new financial consolidation and budgeting system. As one of many inducements, the implementation partner offered to include a tax data warehouse for a fraction of the true cost. Corporate leadership was told that the warehouse equated to a giveaway worth more than $1 million. Leadership was swayed.

Gary’s tax group eagerly engaged and started brainstorming about how a tax data warehouse could improve their processes and change the company. As the project got underway, the tax group participated in discussions about requirements. Optimism quickly spread.

Then came the big presentation in which the design of the tax data warehouse was revealed to the tax group and other stakeholders. Their enthusiasm turned out to be painfully short-lived.

The implementation partner had designed a warehouse that contained the summary-level general ledger account balances, consistent with summary-level detail in the financial consolidation and budgeting system. But it lacked any transaction-level detail, not to mention any drill-down capability for eighty-three different source ledgers at Gary’s company.

The company had grown from a significant number of acquisitions over the years, and its owner was committed to fostering an entrepreneurial spirit. One way he did this was to allow each acquired business to keep as many of its internal processes and systems intact after the acquisition as possible. In other words, the owner did not advocate system integration or standardization.

As a result, at the time of this project, there were eighty-three separate accounting systems in production, and the tax group relied on all eighty-three to capture the detailed information they needed for compliance, provision, and planning.

So, for the tax group, the tax data warehouse as designed was useless.

Sure enough, this did not end well for the tax group. Leadership was unwilling to make funds available to change the tax data warehouse design. They didn’t understand why something that worked for financial consolidation and budgeting would not work for tax.

Gary told us this story because he wanted to emphasize two ground rules in his new role as VP of tax. One, he intended to be personally involved in voicing the department’s challenges and articulating its business needs. Two, he was putting us on notice that he would explain to leadership the business value of projects and technology tools. He would tell the story.

The Power of Storytelling

Stories can trigger passion, inspiration, and loyalty. Compelling ones inspire emotional investment. And this doesn’t apply only to bedtime, campfires, and dinner tables. Fortunately for tax professionals, stories can fire up the boardroom, too.

Storytelling is one of the most persuasive forms of communication because of the emotions stories touch. Good stories forge a strong connection with the audience and paint a clear picture of what could be. In a corporate context, storytelling and funding have a very strong correlation. The better the story you tell when requesting funding for a project or technology tool, the better the chances of approval.

Tax professionals work hard, and they deserve the best technology tools. However, in many cases, their storytelling abilities to request funding for projects or technology tools do not match their tax expertise—a major reason that the projects or tools they propose very frequently are not approved.

By improving your storytelling, you can improve your business. Doing so requires thought, organization, and a proven process. Putting everything together can unlock your persuasive powers and clear your path to the project or technology tool you covet.

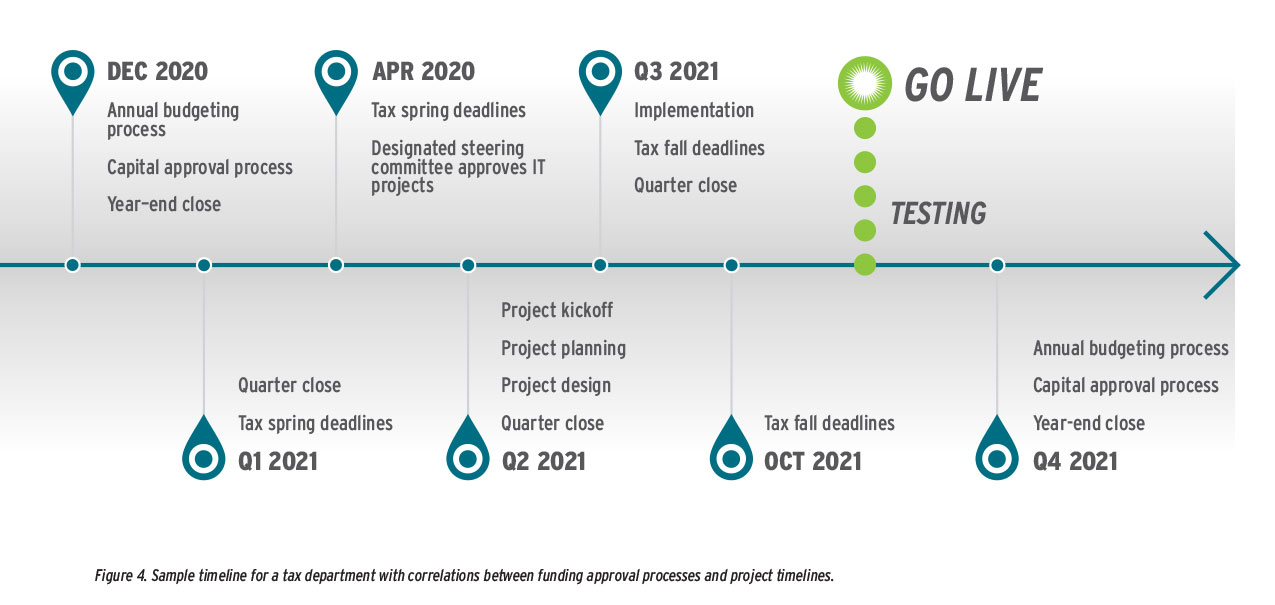

The Solution Flowchart

As shown in Figure 1 below, telling a compelling story works like a flowchart. It’s a multifaceted process that begins with identifying and clarifying challenges and potential solutions. That, in turn, creates a framework for building and presenting a business case. Encasing a value proposition in a storytelling wrapper can provide logistical and emotional clarity to everyone involved. The following sections spell out the seven steps to developing a compelling story, as shown in the flowchart.

Understand Your Challenges

Start by recognizing the daily challenges you face in your job. For a tax professional, it could be any of the following:

- wrestling with data management;

- doing mundane and repetitive tasks and running out of time on tasks that actually add value;

- spending more time on outdated, disparate systems to make things work, when the task could be completed faster or better outside the system; and

- experiencing “analysis paralysis,” or being unable to see the big picture or actionable insights to make meaningful decisions.

Prioritize

Prioritize

Prioritize (from highest to lowest) which of these specific challenges is most pressing in light of various factors:

- the time needed to complete the process—if something takes too long, a better way to do it with a technology solution probably exists;

- how tedious or labor-intensive it is;

- the potential for human error;

- the impact on employee morale;

- how repeatable it is;

- how the data in question is structured or unstructured; and how standardized the process is (rules-based or otherwise).

Make a list of all processes within your purview in the tax department. This list depends on your role within the department and your areas of focus. Identify the tasks that have always been done a certain way and consider why they are done that way. Additionally, examine why different people and groups accomplish related processes in different ways, even when at the core they really are the same process. When thinking about this, do not restrict yourself to one particular area or target a particular type of process.

Identify Problem Areas and Potential Solutions

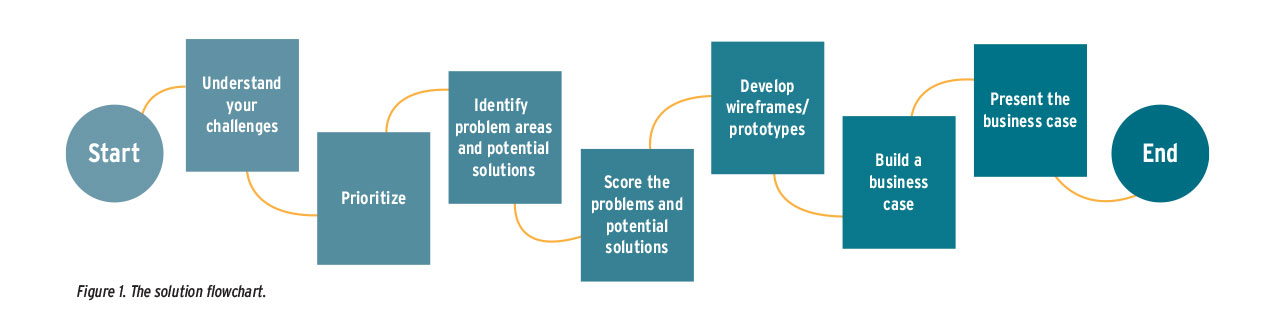

Once you have a comprehensive list of tax processes prioritized based on the challenges above, take the top three in the list for consideration. Then, come up with the best technology tool or project that you genuinely believe will address each area of concern. Of course, some research will be involved, including talking to friends and colleagues and attending industry webinars. Here, you can see a summary of where your biggest pain points lie and how to address them.

Having the support of people within your team or department will strengthen the case you eventually bring to decision makers. Recruiting members of your corporate community can provide fuel for your fire. Consider how or why anyone else in your team or department should care about these pain points. To that end, some social media channels can demonstrate measurable levels of support, such as the number of likes on a SharePoint site. Here’s an example of what these connections between problems and solutions would look like:

Score Problems and Potential Solutions

The next step is to take your list of problem areas above and weigh it against several factors, listed below, to see what solution would result in the highest business value. In this context, business value is the metric that would make decision makers say yes or no to a project or technology tool based on the net value it could provide the company. This is not an exhaustive list, and you can tailor these considerations to your department or company. Does this project or technology tool: align with your corporate strategic goals?

- align with your department strategic goals?

- increase revenues?

- reduce costs?

- result in improved efficiency or productivity?

- improve employee morale?

- differentiate your tax department and your company?

- reduce downtime?

- or attract great talent to your tax department?

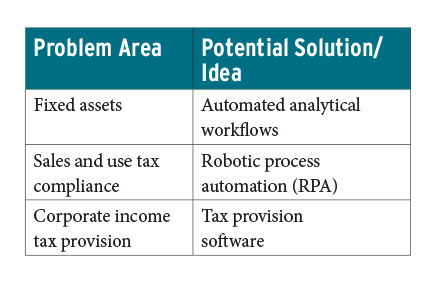

The top three solutions in your version of the problem areas chart can be rated against these factors on a scale of 1 to 10 in a matrix format. The solution with the highest score should be seriously considered a candidate for which you can develop a detailed business case. Make sure your business case incorporates a strong story to make your argument more convincing. An example of the matrix with the individual and total scores against factors appears below.

Depending on your department’s situation, you can assign more weight to a particular attribute (i.e., “increased revenues” can be weighted at twenty percent instead of at ten percent like other attributes), but for the sake of simplicity in the example below, we have assigned equal weights to all attributes.

Depending on your department’s situation, you can assign more weight to a particular attribute (i.e., “increased revenues” can be weighted at twenty percent instead of at ten percent like other attributes), but for the sake of simplicity in the example below, we have assigned equal weights to all attributes.

In the example above, the RPA project for sales and use tax compliance has the highest score and should be the one for which a detailed business case should be written. The factors rating shows that this provides the highest business value. You can assume, then, that this would have the highest potential to be approved by decision makers. Of course, the business case has to be augmented with a great story, return-on-investment (ROI) analysis, and governance and risk analysis.

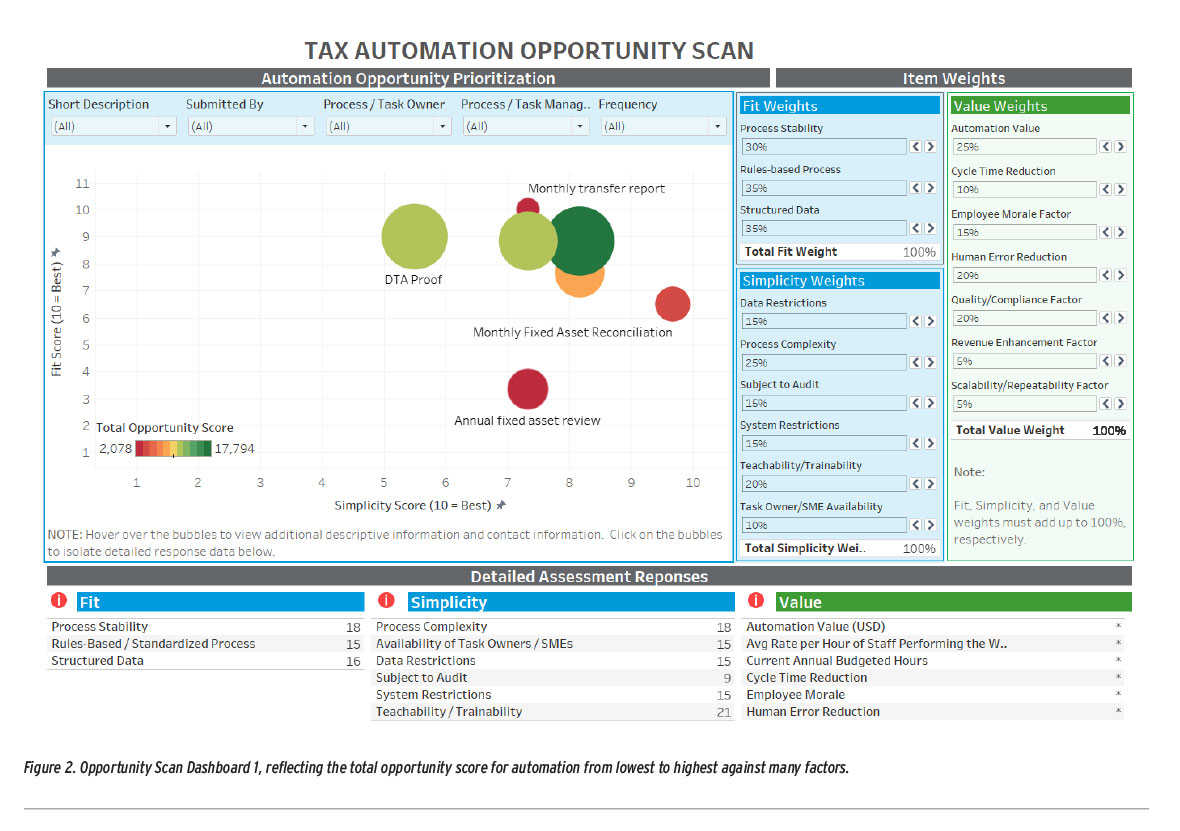

Stories with a visual component, such as illustrations or graphs, are usually more compelling. Figure 2 shows multiple challenges within the fixed assets area in the tax department. Weights and scores are assigned, and results are rendered in dashboards in real time.

In this example, which focuses on tax process automation, the larger and darker green the bubble, the more the specific tax process is ripe for automation. Conversely, the smaller and darker red the bubble, the less ripe that specific tax process is for automation. Develop Wireframes or Prototypes If your business case is not for a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) licensed tool, putting together a quick prototype or proof-of-concept for your idea can provide decision makers with some visual context. This does not have to be extensive, but two to three screens can be wireframed or prototyped. Wireframing is the most cost-efficient, low-effort way to visually present an idea. Several free tools are available to construct a basic wireframe. The key here is to present a visual snapshot of your idea, but not to put together a book of pictures. When applicable, these wireframes should be attached to the business case to tell a visual story to the audience. Enabling others to visualize your story with the help of wireframes will strengthen your case.

Develop Wireframes or Prototypes

If your business case is not for a commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) licensed tool, putting together a quick prototype or proof-of-concept for your idea can provide decision makers with some visual context. This does not have to be extensive, but two to three screens can be wireframed or prototyped. Wireframing is the most cost-efficient, low-effort way to visually present an idea. Several free tools are available to construct a basic wireframe. The key here is to present a visual snapshot of your idea, but not to put together a book of pictures.

When applicable, these wireframes should be attached to the business case to tell a visual story to the audience. Enabling others to visualize your story with the help of wireframes will strengthen your case.

Build a Business Case

The business case for your dream project or technology tool is crucial to winning approval for it. As you build the case, put yourself in decision makers’ shoes and look for all the ways they could poke holes in it. You might get only one chance, and if you don’t make the best impression, the opportunity could be lost. With that urgency in mind, consider engaging an internal or external coach to provide some guidance. Ask them to review your business case before putting it on paper to capture diverse perspectives and alternative points of view.

Keep in mind the this business case document is not just a formal document. It’s a megaphone through which you tell the story of why you need funding. Your goal is to convince your audience to approve the funding request by illuminating how the tool solves problems and adds value.

Business case formats can vary among organizations and sometimes even across departments within a company. But for any successful business case, the following components are necessary to tell a compelling story.

- Executive summary. This is the best place for you to establish all the elements of your story. Remember the five w’s and one h—who, what, where, when, why, and how. The executive summary should feature the context, characters (who), conflict (why), the main idea (what), and the resolution (how) of your situation, and should specify the when and where as needed. Remember, this is an executive summary, so you need to be clear and concise. The goal is to grasp the interest of decision makers so they will read the rest of the document—and pay attention to it.

- Problem statement. Explain the business problem or issue you have been facing by giving it a practical human touch. The problem statement should be brief and get directly to the point.

- Solution to the problem (and any alternate solutions you have considered). State your proposed solution, then explain how you arrived at this solution and why you believe it’s ideal. In our example, it’s why investing in an RPA technology tool will solve the sales and use tax compliance issue in the tax department.

If you have analyzed any alternate solutions, list those here, but be brief about why any alternates were not explored further. The goal is to strengthen your case for the proposed solution and keep it focused, not dilute it. - Costs vs. benefits analysis. For most decision makers, this section is particularly important, so be sure to present a complete picture here.

Show the breakdown of all costs, and show the total costs summed up. If you are pursuing a technology tool, include not just the licensing costs of the tool but also any related training costs, consulting fees, implementation costs, and hardware or software upgrade costs. If it’s a project, list the summarized costs, such as software, hardware, team resource costs, consulting fees, and travel expenses.

Show the breakdown of all costs, and show the total costs summed up. If you are pursuing a technology tool, include not just the licensing costs of the tool but also any related training costs, consulting fees, implementation costs, and hardware or software upgrade costs. If it’s a project, list the summarized costs, such as software, hardware, team resource costs, consulting fees, and travel expenses.

When putting together costs, consider the total cost of ownership (TCO) concept to include all the costs of acquiring that technology tool or completing that project. Do your best not to omit information whose later emergence might surprise decision makers. If certain cost-related facts are not known, then note these as areas that require additional follow-up once the project receives initial approval.

Benefits are often not just quantitative; they can also be qualitative or intangible. Start with the quantitative benefits, such as increased revenues, cost savings, and employee hours saved, among others. Then move to the qualitative benefits, such as improved employee morale, employee engagement and satisfaction, future of work factor, reputation in the industry, differentiation factor, and other possible benefits.

While these benefits may not be easy to quantify, sharing short stories while presenting this information can convince stakeholders and decision makers to take the proposal seriously. Because you have done your due diligence on the benefits of the project or technology tool, this section should reflect that conviction.

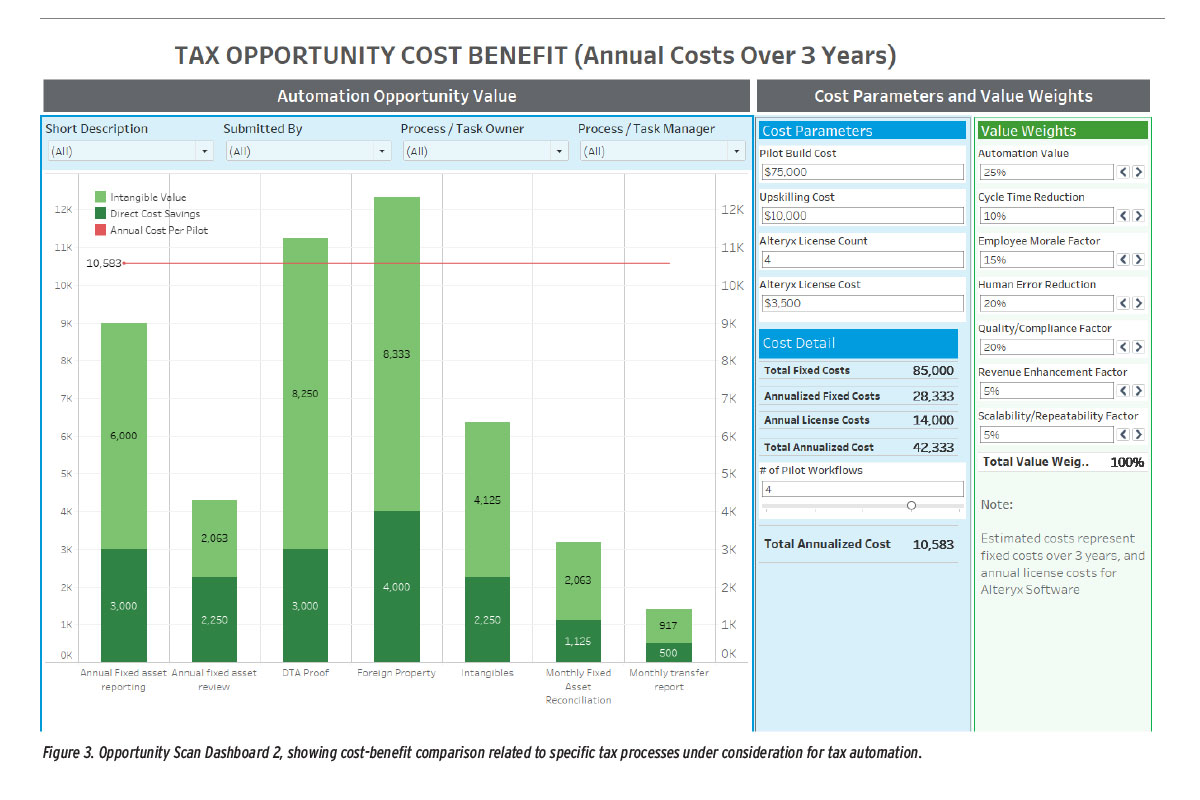

Costs-versus-benefits stories with visual elements are helpful. In Figure 3 on the previous page, which focuses on tax process automation, the stacked bars represent a specific tax process. The dark green part shows the tangible (direct) cost savings; the light green part shows the intangible value of automating that tax process; and the red line shows the average annual cost per pilot per process.

- Expected return on investment (ROI). The expected ROI for the project or technology tool should be calculated for the next five years. There are several ways to make your case stronger by showing ROI, leveraging internal rate of return (IRR), net present value (NPV), and the payback period (in years). Depending on whether it’s a project or a technology tool, the right method can be leveraged to strengthen your case.

- Risks. Highlight any risks related to the project or technology tool in the interest of full disclosure. These are the risks that can come into play if things do not go as expected. Highlight two to four potential major risks here. This does not need to be a risk register; it’s a way to give a well-rounded view to decision makers, who truly should be aware of key risks. Having some risks is not a negative. It can be framed as a positive, because risks—and rewards—are inherent in any investment.

- Recommendation. The formal recommendation for the project or technology tool is like a conclusion to the story that has been told throughout the sections above. Be clear and confident in your recommendation so there is no ambiguity.

- Project or technology tool proposal. Make your vision real. If you are proposing a project, highlight aspects of project roles and responsibilities, project governance, progress reporting, and other relevant project management aspects. If it’s a technology tool, detail how that would be put into practice.

- Attach the wireframes/prototypes. As a final step, attach the wireframes or prototypes developed for your idea with the business case.

Present the Business Case

Once you have built a rock-solid business case, usually the next step is to present it. Thoughtful, detailed preparation will substantially increase your chances of acceptance.

-

- Find allies and get their buy-in before the formal presentation. These could be the staff working under your supervision in the tax department or your immediate bosses (if you are staff), or both. Find people who are on board with the idea, have bought into it, and will stand with you and your idea before you make that formal presentation to the audience (including beneficiaries, stakeholders, and decision makers).

- Be prepared to answer questions. As with any presentation, the more you anticipate audience questions, the better you can be prepared to respond. Make sure to incorporate short stories into your answers to make the story real to your audiences. These short stories in your answers can be in the format of problem, solution, and the benefit. Relate your responses back to your case.

- Keep the presentation simple and straightforward, and start it with a story. You want your audience to understand the presentation easily. Avoid going into too much technical detail or analysis. Once again, incorporate a key story to start the presentation. This should be a story that grabs the attention of the audience and appeals to their compassion. While listening to the story, they should feel that they have a stake in the outcome.

- Be confident in your answers. Answering questions clearly and succinctly conveys confidence. This will make you appear credible and trustworthy, traits that are important to convincing decision makers.

Hierarchy of Funding

Funding for initiatives (including projects or technology tools) within most large corporations can come in several forms. The most common are:

- the annual budgeting process;

- the capital approval process; and

- a designated steering committee that reviews business and IT expenditure requests.

It is important to know and understand all three processes and how they affect funding for various IT projects and technology tools. That understanding will inform how you think through and plan your project or acquisition of the technology tool and your business case for funding.

If you are not familiar with funding process details, learn about them as soon as possible and clearly understand what will be expected for consideration. Find a mentor or a coach internally who knows these processes to help you better understand these considerations.

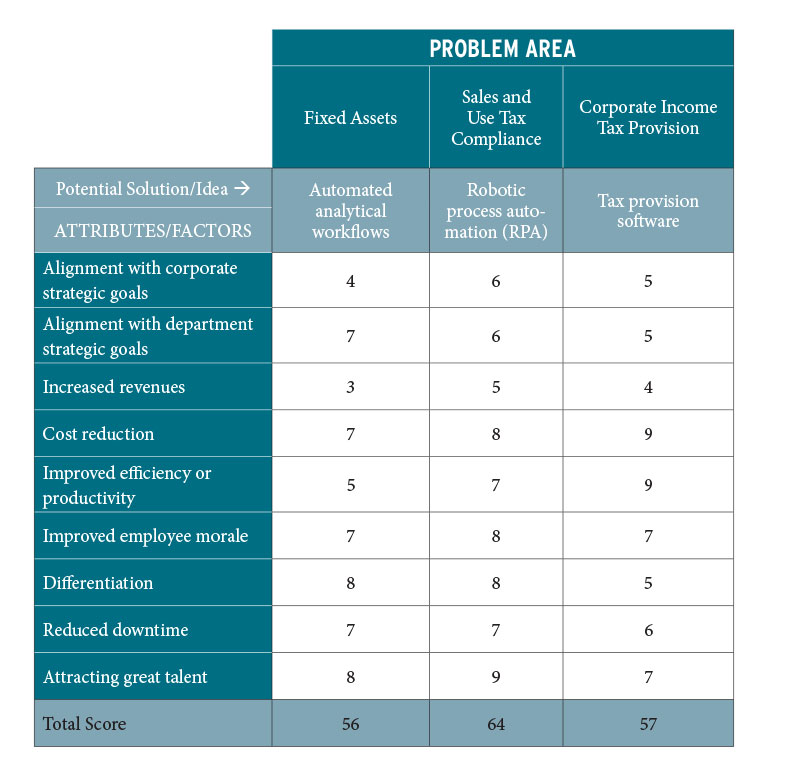

It’s also important to be mindful of how the funding process and timeline for your project will match up with other business processes. For a tax department, business process timelines may include the month-end close, quarter-end close, year-end close, and various tax filing, extension, and payment deadlines throughout the year. (For a sample, see Figure 4 on the previous page.) Allow enough time for decisions, planning, design, implementation, testing, and go-live of the project or technology tool rollout.

Closing Statement

A well-crafted story will elevate your funding request. Inspire your company’s investment in tax solutions by developing a story to supplement research, analysis, brainstorming, business case artifacts, and your understanding of internal funding processes. By pulling back the curtain to show decision makers a conflict and a resolution with a human touch, your presentation is more likely to have a happy ending.

Danish Qureshi is a senior manager and Elizabeth Sponsel is a partner, both in the national tax technology consulting practice at RSM US LLP.