With public country-by-country reporting (CbCR) on the horizon, companies with operations in Europe or Australia may soon have to disclose key information about their tax and business operations by jurisdiction. Companies with operations in Romania may be required to produce public CbCR filings as early as December 31, 2024 (for 2023 calendar-year data).

Reputational risk may be a major concern for companies. After all, investors, analysts, the media, employees, customers, and communities will have access to their newly public data. These stakeholders may run analytics on the information and draw conclusions about a company’s tax position and broader commercial profile. Public CbCR data could include commercially sensitive information, such as margins and the nature of a company’s activities by country. How much profit a company generates and how much it contributes through taxes may also draw scrutiny.

Many companies are responding by looking at data readiness, reviewing their tax governance, and potentially increasing their mandatory and voluntary disclosures on tax. Many public CbCR data points have some crossover with Pillar Two as well as with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards and other regulations. Companies can front-load current work on Pillar Two data readiness to address public tax CbCR/ESG reporting requirements (including definitional differences between qualified CbCR safe harbor data points and public CbCR definitions). The patchwork of increasing requirements has led some companies to think holistically and to consider attaching narratives to the newly transparent figures to meet complex stakeholder needs. Companies can choose from a range of disclosures, from meeting only minimum requirements to publishing various documents, including sheets on tax key performance indicators (KPIs), tax policy, added tax topics in their ESG reports, and full tax transparency reports.

Trust and transparency are becoming more intertwined as US and international ESG standard-setters and government regulators increase requirements in jurisdictions where stronger tax governance and transparency are becoming business imperatives. Societal and market forces have heightened the importance of companies’ ESG strategies, and tax is emerging as one of the latest ESG indicators, with expansion of metrics to cover tax governance and transparency. Tax leaders are engaging with their various internal stakeholders (such as companies’ C-suites, boards of directors, legal teams, and sustainability leadership teams) on reporting and articulating a cohesive tax narrative.

Public CbCR Requirements in the EU and Australia

Public CbCR regulations in the European Union (EU) will require multinationals with annual global consolidated revenue exceeding €750 million and active in the EU to publish certain tax information on a country-by-country basis annually. Key tax and business data includes the nature of the company’s activities; the number of full-time equivalents; revenues; profit or loss before income tax; accrued income tax; income tax paid; and accumulated earnings. Public EU CbCR is continually evolving, and guidance on the EU directive is still forthcoming. To comply with public EU CbCR, companies will need to publish this CbCR data on the website of the relevant chamber of commerce and on their own websites for five years.

Businesses whose calendar year ends December 31, 2025, must publish their reports by December 31, 2026, to comply. However, some member states have been allowed to apply the public CbCR rules sooner, and so far Romania, Croatia, Sweden, Hungary, and Spain have chosen to do so. Non-EU- headquartered multinationals should comply with the public CbCR rules for any specific jurisdiction where they are present through at least one medium-sized or large entity in the EU or an equivalent branch. In this context, the EU rules require that two of the following three criteria be met: 1) €5 million balance sheet total; 2) €10 million net revenue; and/or 3) an average of at least fifty employees during the fiscal year. A branch needs only to meet the revenue threshold. It should be noted that each member state may have different thresholds to consider, and where a company reports may have significance. Countries to be reported include EU member states as well as jurisdictions that the EU lists as “noncooperative” or “gray.” Other jurisdictions may be aggregated.

In June 2024, Australia’s federal government sent Parliament draft legislation for a similar requirement to make public some country-by-country data for fiscal years ending on or after July 1, 2024, to be due 365 days later. The information slated for publication in Australia is broadly aligned with the EU’s own directive, with some different data requirements. Specifically, CbCR reporting applies to parent companies with annual global revenue of AU$1 billion or more in the year preceding the reporting period, and where at any point during the reporting period they, or a member of their CbCR group, are an Australian resident or foreign resident with an Australian permanent establishment. CbCR groups are not required to publish where the group’s aggregated turnover is less than AU$10 million of “Australian-sourced income.” However, the test to determine Australian-sourced income is very broad, and entities should exercise care in establishing the amount of Australian-sourced income for all connected entities and affiliates. Countries with Australian reporting requirements include Australia as well as more than forty specified jurisdictions, including Hong Kong, Singapore, and Switzerland. The remaining jurisdictions may either be aggregated or reported on a country-by-country basis. Although other jurisdictions may be aggregated, companies may find that their aggregated data may be misleading, and reporting on a full country-by-country basis may be more appropriate.

The latest draft of the Australian public CbCR regulation aligns more explicitly, from a definitional perspective, with GRI 207, the tax reporting standard the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), a leading ESG standard setter, issued in 2019. This standard provides guidance for organizations reporting on tax as an ESG topic. Although the standard has been slowly growing in adoption, the draft Australian regulation, if passed, is likely to strengthen its position as a core reference point in the years ahead. In addition to tax and business data (similar to GRI 207-4), Australia’s draft legislation also requires companies to report a description of the CbCR group’s approach to tax, referencing GRI 207-1 as the relevant guidance. The guidance states that the following information shall be reported:

the organization’s tax strategy, if any, and a link to this strategy if publicly available;

- the governance body or executive-level position within the organization that formally reviews and approves the tax strategy, and the frequency of this review;

- the approach to regulatory compliance; and

- the way by which the company’s tax approach is linked to the organization’s business and sustainable development strategies.

Considerations for Reporting

To meet the minimum requirements for public CbCR, companies could publish a simple list of the public CbCR data without context or narrative. Investors, analysts, employees, customers, and communities will have access to this public information and may run analytics on it to draw conclusions about a company’s tax position and broader commercial profile.

Companies could prepare their data for reporting by identifying and mapping an inventory of tax data points to data sources. This will help identify overlap

between Pillar Two, CbCR, and expanded ESG reporting. While public CbCR focuses on corporate income tax data, other tax disclosure standards and requirements are broader, such as reporting all payments to governments. Globally, tax transparency regulations focused on payments to governments have existed for many years in some industries, including oil and gas and financial services. Closer to the United States, Dodd-Frank 1504 is a Securities and Exchange Commission rule mandating detailed tax transparency for US-listed extractive companies (with initial disclosure due September 2024 for calendar-year companies). Canada, the EU, and the United Kingdom have similar regimes in mining, and the EU has parallel regulations for the financial services industry.

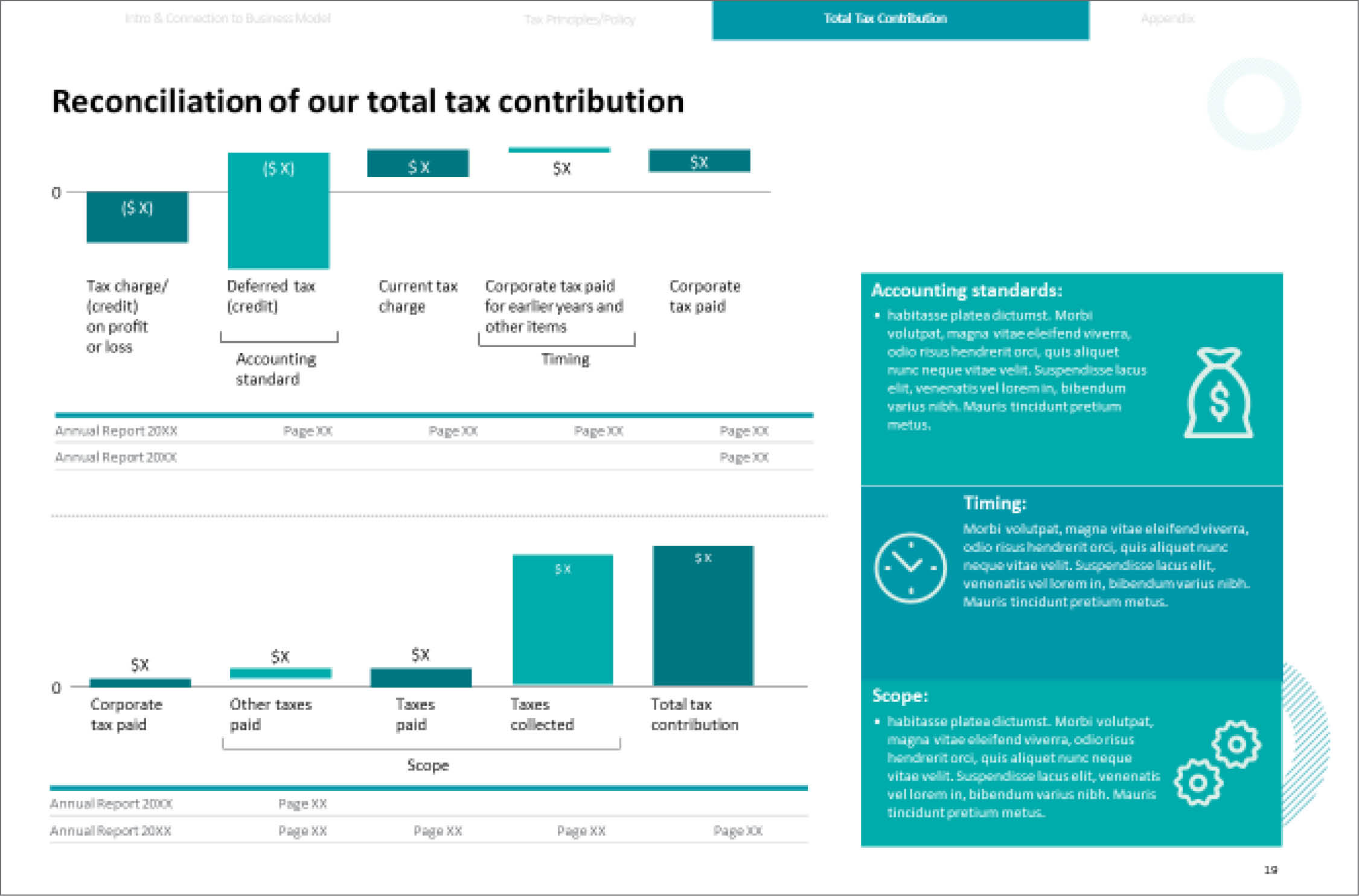

As part of these payment disclosures, companies may opt to disclose other taxes paid or collected such as excise taxes, indirect taxes, property taxes, and others to provide a more comprehensive view of their total economic contribution through taxes. Reconciliation will also be key to ensuring that data presented in various public disclosures is consistent. Collecting, presenting, and analyzing an initial wave of data during a dry run can provide key insights ahead of report delivery.

Companies can choose from a variety of disclosures and reporting mediums. As noted earlier, options range from meeting only the minimum requirements to publishing a table of total tax contributions in the aggregate, producing a tax KPI sheet, publishing a tax policy, adding tax topics in the ESG report, or publishing a full tax transparency report.

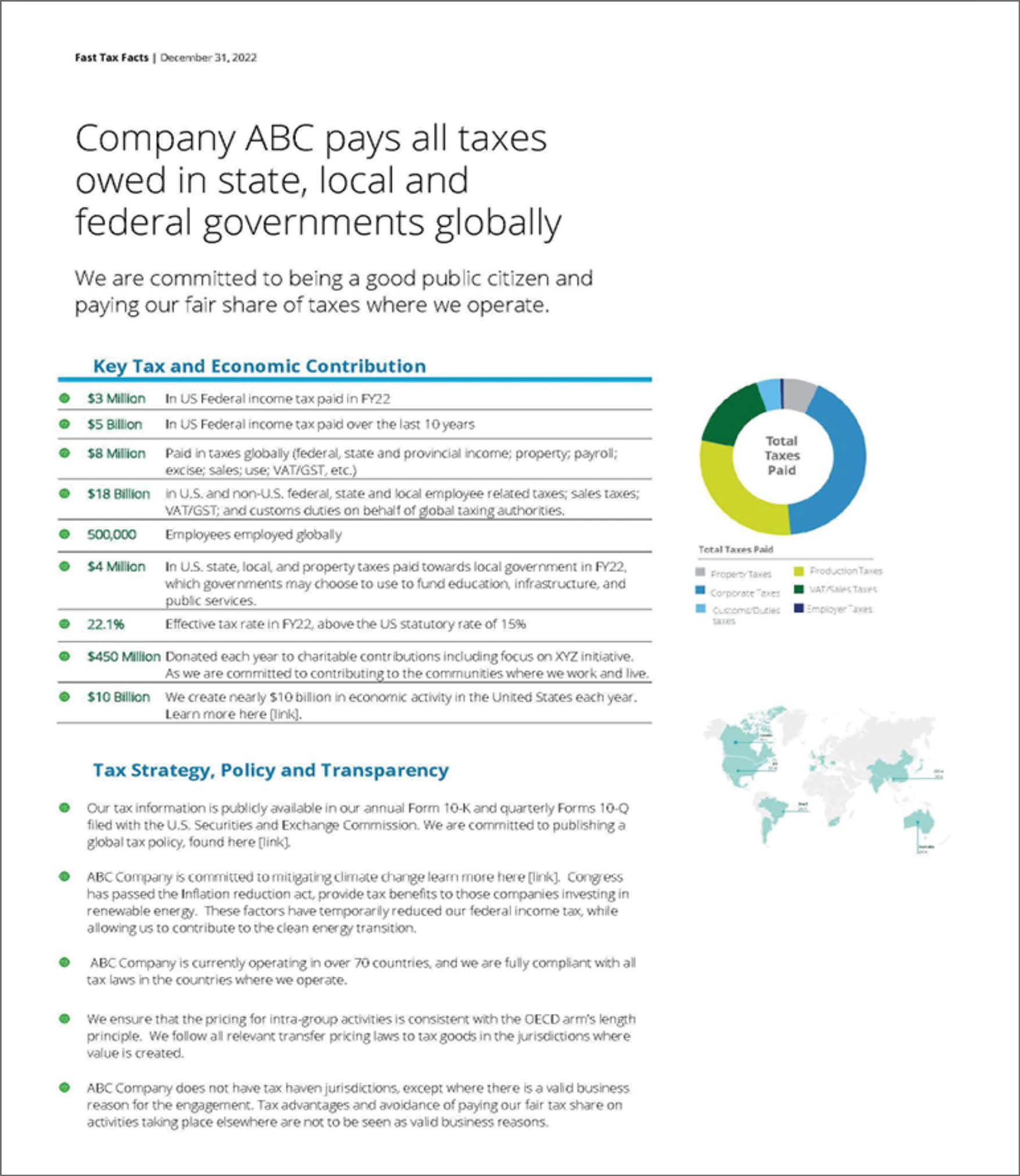

Preparing a Tax KPI Sheet

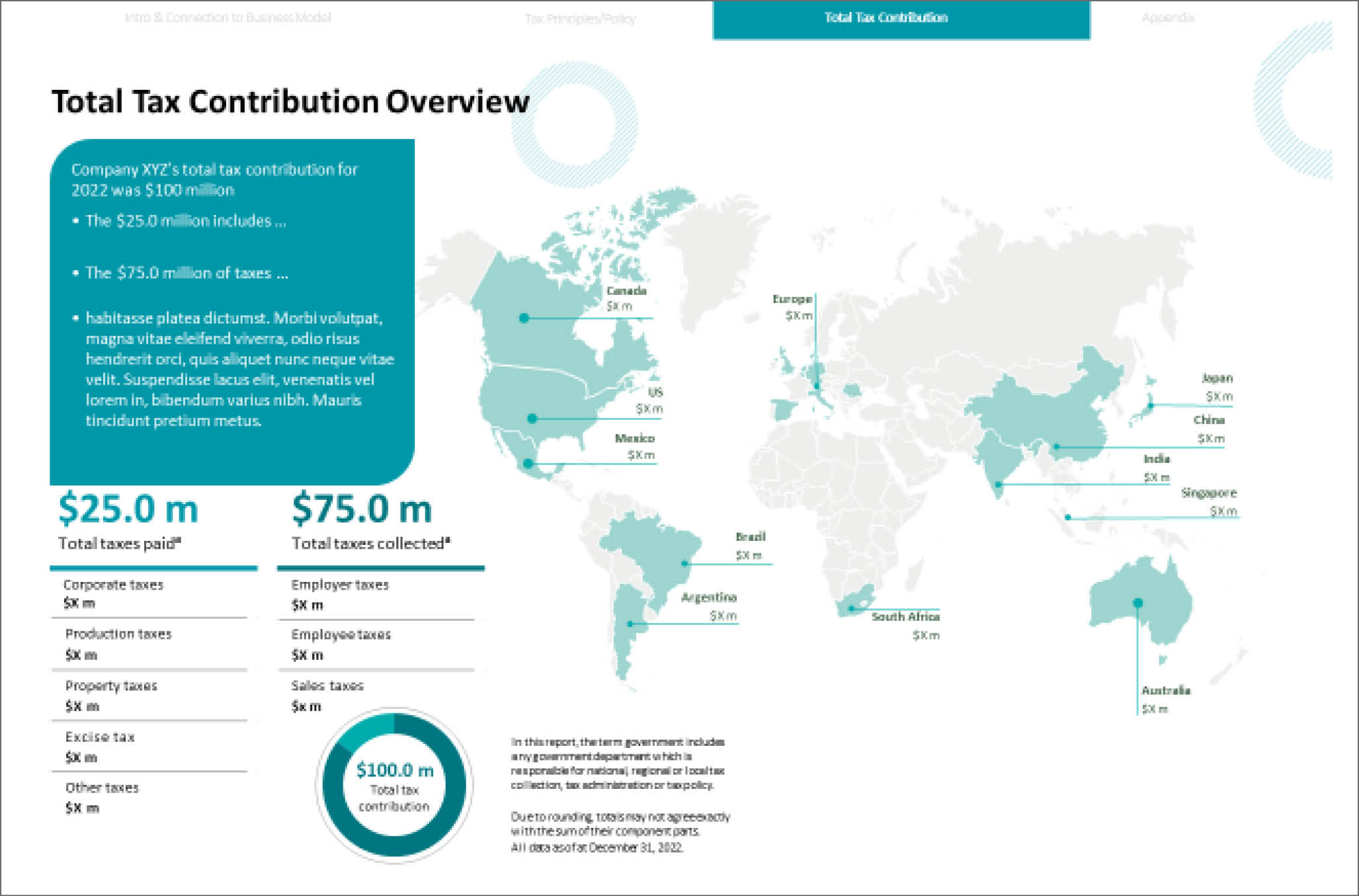

Some companies develop a tax KPI sheet as a first step toward transparency. It could be a one- or two-page document posted separately on the company web page, with the goal of providing key data on a company’s tax profile (see Figure 1 for a hypothetical example). Such documents could also serve as internal reports to educate the business or board on quick tax facts. Examples of tax KPIs could include high-level information such as total tax contribution, effective tax rates, and total income and could also include further details around total tax by tax type or by region or country. This is also a good place to include quick facts on tax strategy and policy.

Incorporate Tax in ESG, Sustainability, and Other Reports

GRI 207 includes three other sections in addition to reporting a company’s approach to tax. They are GRI 207-2 (tax governance, control, and risk management); GRI 207-3 (stakeholder engagement and management of concerns related to tax); and GRI 207-4 (country-by-country reporting), which includes all taxes paid beyond corporate income taxes. Companies may consider reporting against these three additional sections in an ESG, sustainability, or similar publicly available report.

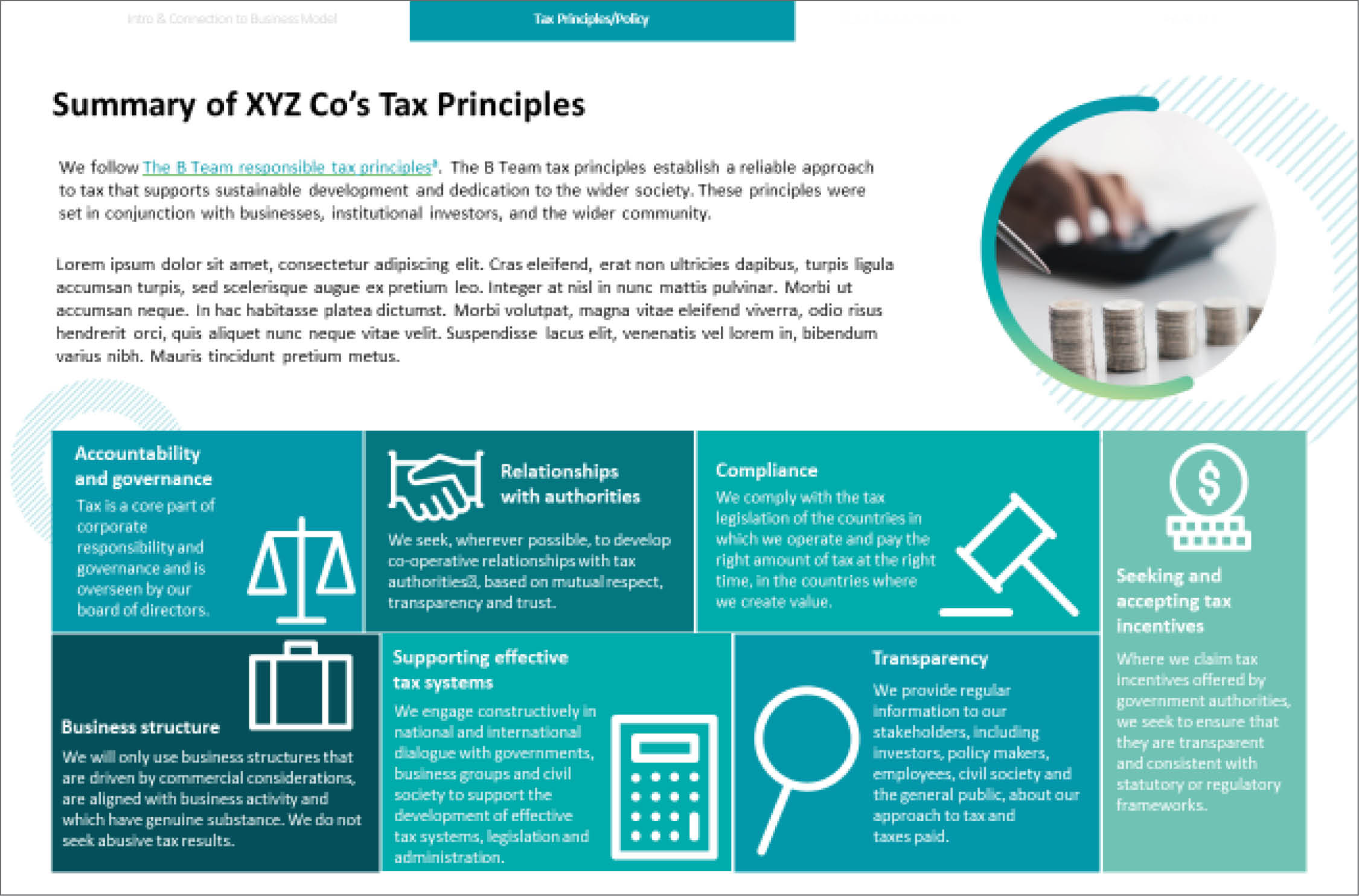

Some companies opt to report according to the B Team’s seven “responsible tax principles” (see Figure 2) by providing nonnumeric examples of how its tax practices support sustainable development and the wider society.

Publishing a Full Transparency Report

Some companies opt to disclose even further, by publishing a full tax transparency report. CbCR does not require one, but some companies may choose this approach for several reasons. Certain tax data may already be required to be made public (either now or in the near future), such as public CbCR data and tax notes in the annual report. The tax transparency report can provide context for that data. Companies can use the tax transparency report to provide a narrative around tax and tell its story, getting ahead of public scrutiny and other messaging produced by stakeholders and external parties (such as the media) that are already viewing public data on tax. Enhanced transparency can increase trust with stakeholders and improve brand image. For companies that use credits and incentives, many of these benefits aim to encourage sustainable investments and behaviors, offering companies the opportunity to highlight their positive impact. Tax transparency also has the potential to improve ESG ratings and alignment with ESG standards.

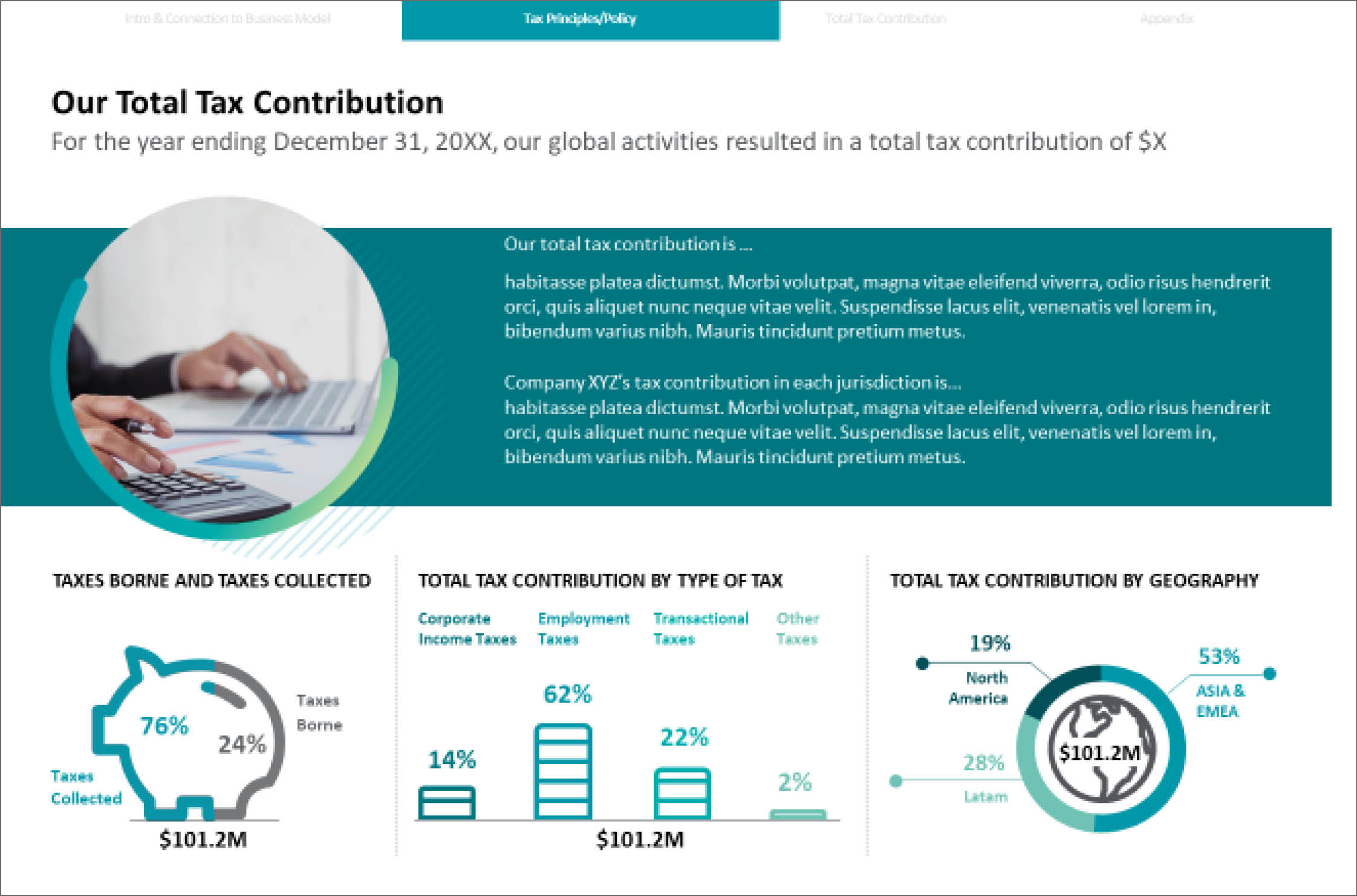

A tax transparency report typically contains twenty to eighty pages on a company’s position on tax. It typically has four main sections:

- An introduction explaining the purpose of the report and providing some tax KPIs. It typically has an executive summary letter from the company’s CFO, CEO, or CTO. It also may include an overview of tax’s correlation with the company’s business model (see Figure 3).

- A section on tax principles (see Figure 4) may outline key components of the tax policy that a company adheres to. Often these principles align with the GRI 207 and/or the B Team principles. A company may do a deeper dive into select principles, walking through how it puts its principles into practice.

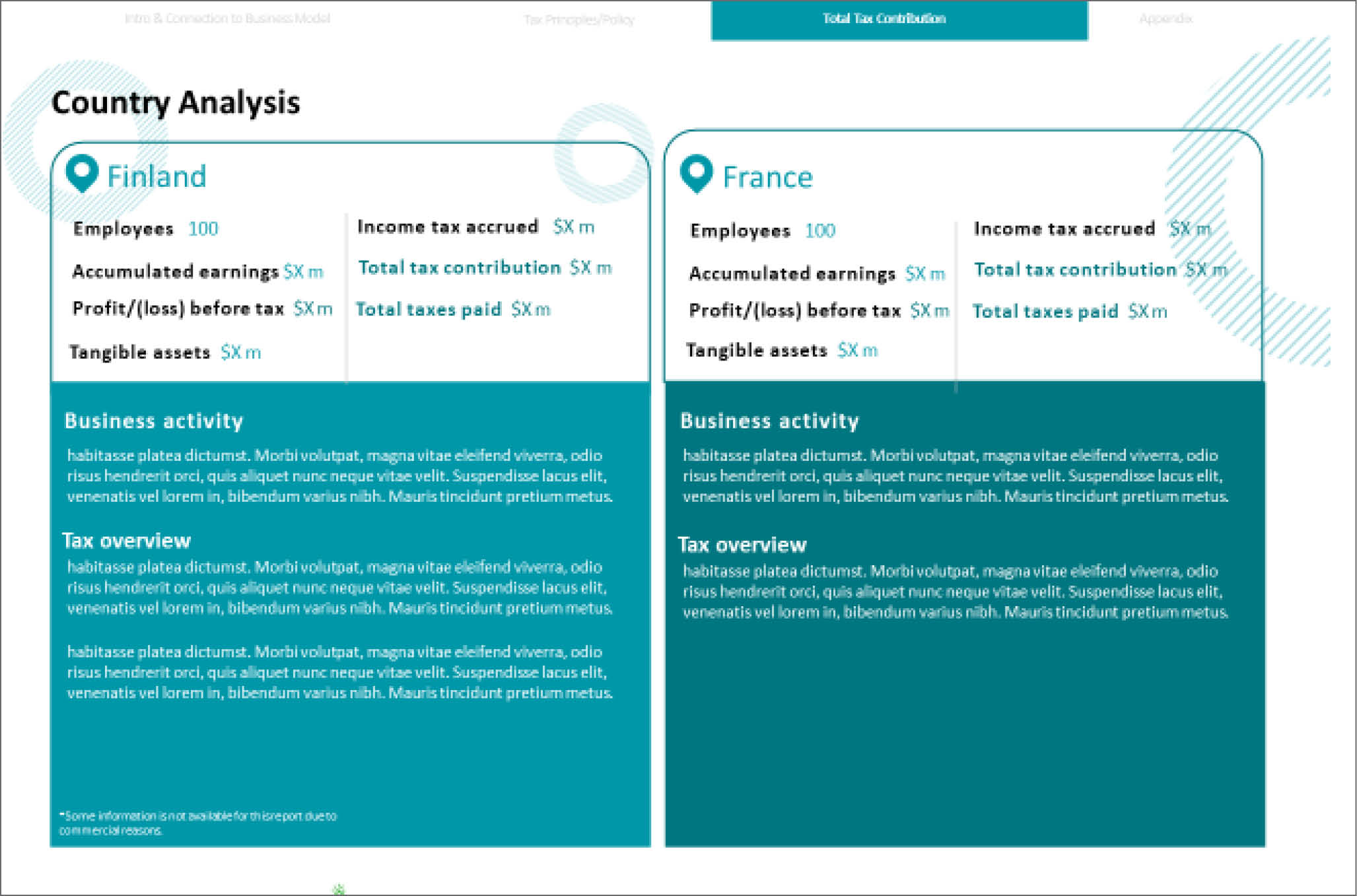

- The total tax contribution section typically accounts for the bulk of the content in a tax transparency report. (See Figures 5, 6, and 7 for samples of hypothetical breakdowns.) It may provide charts of total tax contribution and other graphics that explain the taxes the company pays. This section typically includes a table of the data required in public CbCR. In addition, it may include a write-up of the tax rate and business operations relevant to the company’s operations in each relevant country (see Figure 6 specifically). Some companies may include additional information on tax issues common to their area of expertise that they wish to expand on for interested parties. A company may also choose to include a reconciliation of total tax contribution to other published numbers, such as tax expenses per the company’s Form 10-K, as Figure 7 shows.

- Finally, a tax transparency report typically ends with an appendix outlining the standards used to complete the report (such as GRI 207). These reports have multiple stakeholders in mind, including those analysts, customers, employees and more who may have an interest in public CbCR data, even though they may not have technical tax knowledge. The appendix typically includes a glossary of tax terms, such as “transfer pricing” or “uncertain tax position,” that a nontax technical reader may not be familiar with. Some companies are choosing to get assurance over the report as well.

Drivers of Additional Tax Reporting

Factors beyond public CbCR also create a need for greater tax transparency, with more companies including tax discussions within their ESG, sustainability, and other published reports. Tax continues to be a key topic in sustainability more broadly, with rapid adoption of voluntary ESG standards and topdown pressures on tax to play its part in maintaining these standards. Through credits and incentives, such as the Inflation Reduction Act, tax can identify funding that can help finance the company’s transition to clean energy and other sustainability initiatives. The availability of credits and incentives can help drive demand for green products, such as electric vehicles. In addition, carbon and other environmental taxes can impact a company’s bottom line and may represent a material risk to the company. Social aspects of sustainability are also impacted by tax. Many credits and incentives have social requirements, such as meeting prevailing wage requirements and investments in low-income communities. Tax is also seen as funding the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) such as investment in good-quality education. Tax governance and transparency standards, including GRI 207 and the World Economic Forum’s tax metrics, necessitate more formal tax governance, a detailed tax narrative, and disclosure of jurisdictional tax data. Tax is already a core metric in industry and international ESG frameworks including those of the United Nations, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the Extractives Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), and the B Team and other industry bodies. Not only do companies embed tax into their sustainability strategies more and more, but tax is also more regularly discussed and featured in broader sustainability reports. Companies may wish to see how peers already tell their own stories and provide case studies on tax.

In addition to disclosures, tax governance requirements and standards are impacting companies in over twenty countries. Some of these standards, such as Germany’s, pose criminal or civil consequences for violators. The United Kingdom and Poland both require publication of company tax policy over local operations. As noted above, companies with operations in Australia would be required to publish a groupwide public tax strategy should draft legislation pass through Parliament as expected.

Actions Companies Can Take

Many companies ask how they can prepare for the risks and opportunities this upcoming reporting legislation will present. Here are some recommendations companies can follow to prepare for public CbCR:

Data readiness:

- identify and map inventory of tax ESG data points to data sources, which may also include identifying overlap between Pillar Two and CbCR as well as comparison to other published or filed data sources, such as local corporate income tax and CbCR compliance and statutory financial statements;

- identify systems, tools and technologies and analyze data reporting options; and

- evaluate data quality and gain insights through controls, analytics and visualizations.

Governance readiness:

- review and analyze tax policy against peers and standards such as B Team, GRI 207, and Australia CbCR requirements;

- assess governance maturity and tax risk, including analyzing governance versus stated objectives and developing a prioritized road map to address gaps; and

- design, test, and/or review internal tax controls, including testing updates for Pillar Two.

Communications readiness:

- assess company compliance obligations by looking at company locations of operation and at CbCR and other deadlines, including educating company leadership on requirements, timing, and impact;

- analyze what companies are currently publicizing and benchmark against peers and market leaders;

- review ESG reports and analyze against broader reporting standards, such as GRI 207 and WEF, and assess opportunities to include tax in ESG reporting;

- help prepare and implement an impactful communication strategy, including agree reporting, format, audience, and timeline for communications, which may involve a working session with tax, business, and sustainability leaders to analyze strategy and risks; and

- collaborate on draft tax transparency report, draft ESG report, draft tax policy, and other stakeholder messaging on tax.

Taking these actions now will help prepare you for these upcoming disclosures.

Elise Kelly, Diana McCutchen, and James Gordon are all part of Deloitte’s tax governance and transparency practice. Kelly is a tax senior manager, where she advises clients on data strategy, risk, and global tax compliance, with additional emphasis on ESG reporting. McCutchen is a tax partner who co-leads Deloitte’s tax governance and transparency offerings as part of the firm’s sustainability, climate, and equity practice. Gordon is a tax managing director who leads Deloitte’s tax governance and transparency offerings in the United States, after having held a national leadership role in the same area at a Big Four firm’s practice in Australia.