Our article, “GloBE Meets GILTI,” which appeared in the January/February issue of Tax Executive, addressed how taxes on global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) might be allocated. Sadly, the story was already out of date by publication. This follow-up article addresses not the possibilities, but rather what the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) actually did on this issue. It also addresses the safe harbor provisions, which seem at this point to command a lot of attention because getting “scoped out of” the application of the global anti-base erosion (GloBE) rules is greatly preferable to being “scoped into” them.

An extremely challenging future lies ahead for US-based multinationals. The need for tax executives to be able to model potential legislative outcomes effectively and efficiently is urgent.

In this piece, we use “Pillar Two” to refer to the OECD/G20 document titled Tax Challenges Arising From Digitalisation of the Economy—Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two): Inclusive Framework on BEPS and to a second document containing examples of those rules. The executive summary of the GloBE rules (the first document) describes those rules as:

a co-ordinated system of taxation intended to ensure large multinational enterprise (MNE) groups pay a minimum level of tax on the income arising in each of the jurisdictions where they operate. It does so by imposing a top-up tax on profits arising in a jurisdiction whenever the effective tax rate, determined on a jurisdictional basis, is below the minimum rate.1

Under the defined terms, the minimum rate is defined as fifteen percent. OECD member states are expected to enact their own rules that correspond with the Pillar Two rules. Member states that meet these criteria are obligated to enforce the minimum tax, unless there is a higher-tier entity operating in the relevant jurisdiction that itself meets these criteria. As noted, the US Congress could have enacted qualifying rules in July 2022 as part of the Inflation Reduction Act. But it did not, instead enacting the comparatively simple rules of the so-called “book minimum tax” (which is generally acknowledged not to qualify under the Pillar Two rules).

In summary, Pillar Two requires the highest-tier compliant country to apply a specified process consisting of five sequential steps:

- jurisdictional ETR = covered taxes/GloBE income;

- top-up % = 15% minimum tax rate – jurisdictional ETR;

- jurisdictional excess profit = GloBE income – substance-based income exclusion consisting of (5% × payroll) + (5% × tangible assets);

- jurisdictional top-up tax = (top-up % × jurisdictional excess profit) – qualified domestic minimum top-up tax (QDMTT); and

- allocation of top-up tax between low-taxed constituent entities within each jurisdiction.

This article focuses primarily on Step 1, specifically on how controlled foreign corporation (CFC) laws, such as global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI), will affect these calculations. In particular, we address how taxes imposed on the ultimate parent entity of a CFC are allocated to the correct countries for the purposes of Step 1 whose effective tax rates (ETRs) are being tested under the five steps above. The definition of adjusted covered taxes does not specifically list “taxes imposed under a CFC regime” as a component of covered taxes. However, as Article 4.3.2(c) of Pillar Two makes clear, these taxes do apply:

in the case of a Constituent Entity whose Constituent Entity-owners are subject to a Controlled Foreign Company Tax Regime, the amount of any Covered Taxes included in the financial accounts of its direct or indirect Constituent Entity-owners under a Controlled Foreign Company Tax Regime on their share of the Controlled Foreign Company’s income [is] allocated to the Constituent Entity. . .2 [emphasis added].

Four recent developments demonstrate how rapidly Pillar Two is being implemented.

- the publication by the OECD in February 2023 of a broad set of technical topics, one of which is the main focus of this article: how US GILTI taxes (and comparable provisions of foreign law) are to be allocated for purposes of testing the effective rate of tax on income;3

- the OECD’s publication on December 15, 2022, of rules describing a safe harbor in which qualifying business units are “scoped out” of the application of the top-up tax;4

- the publication of a draft version of the GloBE information return (GIR) that would be filed in connection with the GloBE rule;5 and

- the unanimous approval by the European Union of a directive calling for EU member states to implement GloBE.

The EU approval was less a technical development than an answer to the overarching question of how long it will be before all of this technical guidance actually applies. Under the EU directive, all EU member states (with some exceptions for smaller members) must have implementing legislation in place by the end of 2024. Many other major countries are in the same place. The wait-and-see aspect of the global implementation process appears to be over, with the significant exception of the United States.

The one thing that has not changed since our original article in the January/February issue is the likelihood that the US government is going to hear the call. The world we described in the first article—one in which the subsidiaries of US multinationals become subject to Pillar Two long before (or significantly in advance of) their US parents become subject to a US version of the OECD’s new approach—is still where we are. Barring a sudden groundswell of support for US implementation in the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, it is where we are likely to remain for some time.

The discussion below focuses first on the issue of how GILTI is to be allocated among countries for purposes of testing ETR, and then we address the safe harbor rules and the conditions that the OECD has created in its December guidance.

GILTI Allocation

The guidance the OECD approved on February 1, 2023, addresses a wide range of topics. The provisions of paragraph 2.10 address the interaction of GloBE with “blended CFC tax regimes.” A blended CFC tax regime is one in which the tax charge is computed based on a blend of income, losses, and/or creditable taxes of multiple CFCs whose ownership interests are held by a constituent entity-owner (or multiple constituent entity-owners that file a single tax return). The OECD’s authors specified that:

The US Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) regime is an example of a Blended CFC Tax Regime. The GILTI rules aggregate income, losses, and taxes of all CFCs owned by a US shareholder to determine whether that shareholder’s share of the income derived through CFCs is subject to tax at a minimum rate. The GILTI regime was designed to test the global aggregate CFC income of the US shareholder and then impose an additional tax should the globally blended ETR be below 13.125% in a given tax year, as computed under US tax principles.6

The guidance provides a simplified two-step formula to allocating the residual US income tax resulting from a blended CFC tax regime for purposes of determining each entity’s jurisdictional effective tax rate.

In the first step, each entity determines its own blended CFC allocation key according to this formula:

Blended CFC Allocation Key:

Attributable income of entity × (applicable rate – GloBE jurisdictional ETR)

In the case of GILTI, attributable income is defined as tested income of the tested unit without reduction for the foreign income tax.

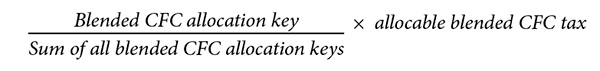

Then, in Step 2, the allocable blended CFC tax is allocated to each of the entities (for example, tested units in the case of GILTI) subject to the blended CFC tax.

Blended CFC Tax Allocated to an Entity:

One question that leaps to mind is whether any country other than the United States has a blended CFC tax regime, or whether the US GILTI regime stands alone in the category. If it does, no one else needs to worry about pushing down the tax imposed under an equivalent regime. It would be useful if the OECD could specify which countries have a blended CFC tax regime so that countries implementing Pillar Two do not need to define, and prescribe rules for, a category of one (that is, US GILTI).

And if the United States is not the only member, it would be useful to know what the equivalent “minimum tax rate” is for that other country or countries. We understand how a twenty-one percent corporate rate coupled with a fifty percent dividends-received deduction results in a 10.5 percent rate, and that a twenty percent disallowance of credits in the GILTI category results in the 13.125 percent threshold. If there is any other country in the category, what math tells us the “applicable rate” for that country?

It is a great simplification to say that the United States has a 13.125 percent minimum tax. But the recent OECD guidance acknowledges that its method for pushing down GILTI taxes is “simplified.” And we are all for simplification. After perusing the twenty-one pages of “data points” set forth in the proposed GIR, one may infer that simplification was not at the forefront of the drafters’ minds.

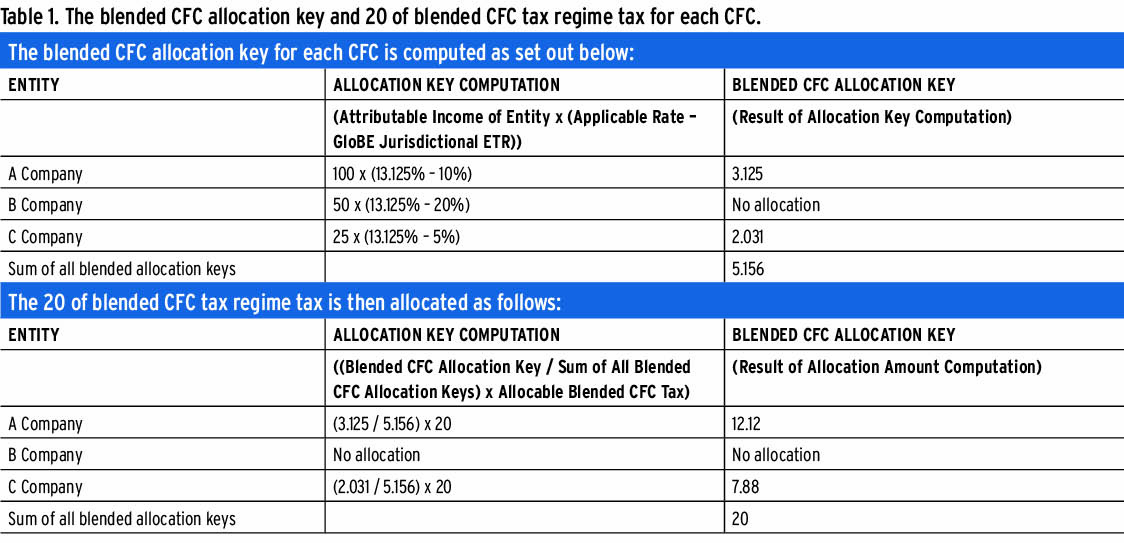

An example illustrating the allocation of the blended CFC tax assumes the following facts: in Countries A, B, and C, the ultimate parent entity owns CFCs that we will call A Company, B Company, and C Company, respectively. For the fiscal year, A Company generates 100 in attributable income, B Company generates 50 in attributable income, and C Company generates 25 in attributable income. The GloBE jurisdictional ETRs (before any pushdown of parent-level taxes on CFCs) are ten percent, twenty percent, and five percent, respectively.

The analysis is that Country B is out of scope because its ETR exceeds the 13.125 percent hurdle rate. Therefore, the 20 of “blended CFC regime” taxes have to be allocated between Country A and Country C, each having an ETR below the 13.125 percent threshold. To do this, one would subtract the jurisdictional ETR from 13.125 percent and multiply the applicable income of the jurisdiction by the resulting percentage. Table 1 shows the result.

Happily, as a result of the very large 20 tax imposed on the ultimate parent entity, A Company and C Company exceed the fifteen percent ETR threshold that the Pillar Two rules require. No top-up tax applies, which is a “victory” for the taxpayer. What the authors do not spell out is that determining the jurisdictional ETR is going to involve a great many data points (as the proposed GIR reveals) and undertaking the many adjustments to income as shown at 3.3.1.1(a) through (x) of the GIR. The effect of these adjustments on ETR will emerge over time as compliance efforts unfold. Nonetheless, it is good to know that A Company and C Company test out of the top-up tax as a result of GILTI push-down.

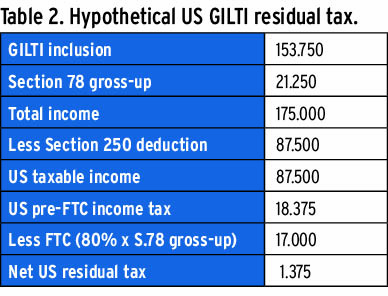

The example does not explain the determination of the ultimate parent’s 20 in residual income tax under the blended CFC regime, which seems inexplicably high. For example, under the GILTI regime, assuming no allocation and apportionment of deductions, the net GILTI tax could be as low as 1.375, computed as shown in Table 2.

Thus, the result derived from a 20 tax charge at the highest tier may overstate the actual benefit of the push-down analysis.

The question here is not who had the most pre-credit US tax liability, but rather who derives the least benefit from US foreign tax credit relief. For US practitioners accustomed to allocating taxes on income amounts, a method driven by the size of the US residual tax on the GILTI inclusion is a bit unsettling. The US rules average together all the foreign taxes in the GILTI basket, whereas the OECD takes apart the averaged US tax and allocates it back to the lowest tax units of the enterprise.

The OECD authors point out that the prescribed allocation rules “logically allocates the tax incurred under a Blended CFC Tax Regime to the Constituent Entities which have the most significant downward impact on the aggregate ETR of the CFC shareholder under the Blended CFC Tax Regime.”7 We absolutely concur that, as a matter of tax policy, GILTI tax should be pushed down before testing jurisdictional ETRs. And we agree that the allocation methodology should be weighted to the entities with the lowest ETR. But this is all predicated on knowing jurisdictional ETR. One wonders if a simpler allocation methodology might result in taxpayer victories—testing out of the top-up tax—without the preliminary calculation of jurisdictional ETR.

Another important question is why the OECD authors have not mentioned the tax imposed on “legacy subpart F income” (meaning the kind of income deemed unworthy of deferral under the laws that existed before GILTI came along in 2017). For this category, we are confident that many nations have incorporated these principles into domestic law, and just as Kleenex has become the noun that covers soft paper tissues, “subpart F” is used to describe the laws these nations have enacted.

Although GILTI probably has much greater materiality than legacy subpart F, it is also a blended CFC tax regime in many cases, such as holding company structures, where the CFC frequently holds operations in multiple taxing jurisdictions with cross-crediting allowed. If that is the defining criterion for a blended CFC tax regime, then the OECD should make it clear that tax imposed under legacy subpart F also meets the standard.

Safe Harbor Rules

On December 15, 2022, the OECD published guidance describing rules that would limit the scope of application of the GloBE rules by deeming a zero top-up tax to apply under the specified facts and circumstances. Within this guidance, there is the “transitional CbCR safe harbour” (bowing to the European spelling) and the “permanent safe harbour.”

We begin with the transitional rules. The OECD authors note that their goal was to:

allow an MNE to avoid undertaking detailed GloBE calculations in respect of a jurisdiction if it can demonstrate, based on its qualifying CbCR and financial accounting data, that in that jurisdiction it has revenue and income below the de minimis threshold (the de minimis test), an ETR that equals or exceeds an agreed rate (the ETR test), or no excess profits after excluding routine profits (the routine profits test).8

These three potential ways out of a more complex GloBE analysis are as follows:

- The MNE group reports total revenue of less than €10 million and profit (loss) before income tax of less than €1 million in such jurisdiction on its qualified country-by-country report for the fiscal year;

- The MNE group has a simplified ETR that is equal to or greater than the transition rate in such jurisdiction for the fiscal year; or

- The MNE group’s profit (loss) before income tax in such jurisdiction is equal to or less than the substance-based income exclusion amount, for constituent entities resident in that jurisdiction under the country-by-country report, as calculated under the GloBE rules.

As with all OECD guidance, there is a raft of new defined terms, which can be decoded as follows:

Simplified covered taxes are a jurisdiction’s income tax expense as reported on the MNE group’s qualified financial statements, after eliminating any taxes that are not covered taxes and any uncertain tax positions reported in the MNE group’s qualified financial statements.

Simplified ETR is calculated by dividing the jurisdiction’s simplified covered taxes by its profit (loss) before income tax as reported on the MNE group’s qualified country-by-country report.

Transition period covers all fiscal years beginning on or before December 31, 2026, but not including a fiscal year that ends after June 30, 2028.

Transition rate means:

- 15 percent for fiscal years beginning in 2023 and 2024;

- 16 percent for fiscal years beginning in 2025; and

- 17 percent for fiscal years beginning in 2026.

We continue to wonder how this will work in practice. Here too the GloBE information return casts some light on how taxpayers will assert the benefit of being in a safe harbor. But the proposed form could make it clearer that the whole point of simplification is to avoid undertaking all the data gathering and manipulation that the form contemplates.

Mark C. Gasbarra, CPA, is the national managing director and David Merrick, JD, is of counsel at Forte International Tax LLC.

Circular 230 Disclaimer: Any tax advice included in this communication is not intended or written to be used, and it cannot be used by any taxpayer for the purpose of avoiding penalties that may be imposed on the taxpayer.

Endnotes

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2021), Tax Challenges Arising From Digitalisation of the Economy—Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two): Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/tax/beps/tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-global-anti-base-erosion-model-rules-pillar-two.htm, p. 7.

- OECD (2021), Tax Challenges, p. 24.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2023), Tax Challenges Arising From Digitalisation of the Economy—Administrative Guidance on the Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two), OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/tax/beps/agreed-administrative-guidance-for-the-pillar-two-globe-rules.pdf.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2022), Safe Harbours and Penalty Relief: Global Anti-Base Erosion Rules (Pillar Two), OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/tax/beps/safe-harbours-and-penalty-relief-global-anti-base-erosion-rules-pillar-two.pdf.

- Public Consultation Document, Pillar 2 Information Return, December 22, 2022, through January 3, 2023.

- OECD (2021), Tax Challenges, p. 67.

- OECD (2021), Tax Challenges, p. 68.

- OECD (2022), Safe Harbours and Penalty Relief, p. 4.