The United States has spent more government aid to combat the COVID-19 pandemic than at any other time in the country’s history. Due largely to pandemic spending, the United States federal government debt increased from $22.7 trillion to $28.5 trillion in the past two years, with much of the increased spending going to corporations to aid their operation and survival.

This article highlights the amount of government aid the United States spent to combat COVID-19 and details the ways in which corporations listed in the Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P 500) stock market index received and disclosed government aid. In addition, it provides graphs showing the types of aid and locations of relevant disclosures. The article examines the accounting rules and guidance that companies followed to report their receipt of government aid.

Finally, this article provides excerpts from annual and quarterly financial reports to showcase how companies disclosed various forms of aid received due to the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Securities (CARES) Act.

Government Assistance Programs for COVID-19

In 2020, the US federal government authorized $3.8 trillion in spending to combat the effects of COVID-19 through legislative bills, including:1

- the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act ($8.3 billion on March 6, 2020);

- the Family First Coronavirus Response Act ($225 billion on March 18, 2020);

- the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Securities Act ($2.2 trillion on March 27, 2020);

- the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act ($483 billion on April 24, 2020); and

- the Consolidated Appropriation Act ($920 billion on December 28, 2020).

Most of this funding was in the CARES Act, which provided $2.2 trillion in government aid to individuals, businesses, state and local governments, and health care, education, and safety net initiatives. The largest proportion of recipients of CARES Act aid were individuals and businesses.2

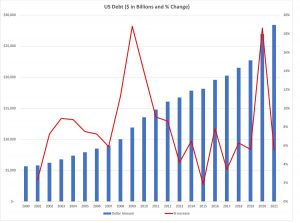

Figure 1 shows the aggregate debt of the US federal government and the year-over-year percentage increase in spending between 2000 and 2021. Debt levels rose from $22 trillion at the end of 2019 to $28.5 trillion through the pandemic. The federal government increased spending by approximately eighteen percent year-over-year to combat the pandemic. Interestingly, it is the same year-over-year percentage debt increase as during the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009. After that financial crisis, the federal government continued its elevated year-over-year spending, with percentage increases above ten percent for several years. The rapid economic recovery, driven in part by historically loose monetary policy from the Federal Reserve, resulted in a more severe decline in government spending: six percent year-over-year growth only one year after the pandemic began.

How Companies Reported COVID-19 Government Aid

To report the government aid companies received, financial statement preparers followed a wide variety of standards as well as none at all, including international accounting standards (IAS 20), not-for-profit accounting standards (ASC 958), and nonauthoritative guidance. Some used their own judgment. And many reported nothing.

US GAAP

In 2015, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) proposed an accounting standard update, Disclosure by Business Entities About Government Aid, that would require companies that prepare their financial statements under US generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) to disclose details of the government assistance they received. However, many organizations opposed the proposed rule, and comment letters suggested that the scope was too broad to apply and too difficult to implement.

In this case, hindsight is quite literally 20/20—the year of the pandemic—where it became evident from COVID-19 relief that defining the scope of and measuring government aid was not necessarily as complex as comment letters suggested, since companies grasped the nature and amounts of the government aid they received. Unfortunately, there was no rule in US GAAP requiring companies to disclose the details.

International GAAP

On the flip side, and quite oxymoronically, the principles-based accounting society (international accounting) had a rule. With no official rule in US GAAP, many financial statement preparers turned to international accounting standards number 20 (IAS 20), Accounting for Government Grants, which requires the following disclosures:

- the accounting policy adopted for government grants and the methods of presentation adopted in the financial statements;

- the nature and extent of government grants recognized in the financial statements and an indication of other forms of government assistance from which the entity has directly benefited; and

- unfulfilled conditions and other contingencies attached to government assistance that has been recognized.3

The total figures of government assistance are straightforward, if substantial, but identifying the corporate recipients of that aid has remained more elusive. The different wrappings of the aid—the Paycheck Protection Program, direct grants, access to low-interest rate loans, tax loss carrybacks to years where rates were at thirty-five percent, payroll tax credits, and the deferral of Social Security payments, among others—have frequently gone unreported and undisclosed in corporate financial reports. Before the pandemic, the spotlight on government aid to companies was often dim. This resulted in an absence of accounting policies or reporting mechanisms for the proper measurement, presentation, and disclosure of government aid from the coronavirus response.

Analysis of S&P 500

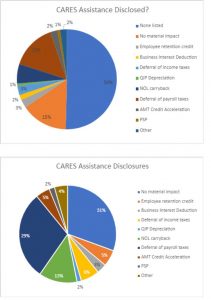

An analysis of financial reports filed by S&P 500 companies4 shows substantial diversity in qualitative and quantitative disclosures of government assistance received through the CARES Act. Half of all S&P 500 companies made no disclosures of CARES Act assistance, and another fifteen percent disclosed no material impact from the assistance.

The top two areas of disclosures were the deferral of the employer portion of payroll taxes, which allows companies to defer remittance of payroll taxes due from March 27, 2020, through December 31, 2020, to December 31, 2021, and December 31, 2022, with fifty percent due on each date. Fifteen percent of S&P 500 companies disclosed that they elected this deferral. The other top disclosure was electing to carry back net operating losses (NOLs) generated from tax years beginning in 2018, 2019, and 2020 with a five-year carryback period. Six percent of S&P 500 companies disclosed this election.

As shown in the top graph of Figure 2, only half of all S&P 500 companies disclosed receiving aid through the CARES Act in their various financial reports. The bottom half shows how the fifty percent that acknowledged receiving CARES Act aid applied that aid to their businesses.

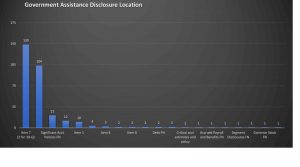

There is not just diversity in the scope and quantity of disclosure, but also in the location where that aid was disclosed in annual reports. S&P 500 companies disclosed government assistance from the CARES Act in twenty different locations within their annual reports. As shown in Figure 3, most of those disclosures were made in Item 7 (management’s discussion and analysis, or MD&A) or the income tax footnote within Item 8 (financial statements and supplementary data). However, disclosures were also common in the significant accounting policies footnote; in Item 1A, risk factors; in and Item 1, description of business.

In addition, government assistance disclosures were found in COVID-19 footnotes, directly within the financial statements, in Item 5, in Item 6, and in several other footnote locations.

Excerpts From Government Aid Disclosures

For some context about how companies reported specific forms of aid, here are excerpts from annual and quarterly reports found using Bloomberg Tax & Accounting’s advanced EDGAR search, which allows quick discovery of CARES Act disclosures. The excerpts are from different companies’ disclosures in their risk factors, MD&A, and financial statement notes sections. Some excerpts have been slightly modified for readability, but not edited or standardized.

Paycheck Protection Program

JetBlue Airways annual report, excerpt from risk factors section: “In April 2020, we entered into the Payroll Support Program Agreement under the CARES Act with the Treasury governing our participation in the Payroll Support Program. Under the Payroll Support Program, Treasury provided us a $936 million Payroll Support Payment, consisting of $685 million in grants and $251 million in an unsecured term loan. On September 30, 2020, Treasury provided a $27 million Additional Payroll Support Payment, consisting of $19 million in grants and $8 million in unsecured term loan under the PSP Agreement. In consideration for the Payroll Support Payment and the Additional Payroll Support Payment, we issued warrants to purchase approximately 2.6 million and 85,540 shares of common stock, respectively, to the Treasury at an exercise price of $9.50 per share.”

Direct Grant

Surgery Partners Inc. annual report, excerpt from MD&A: “As a result of the CARES Act and other governmental assistance programs, during the year ended December 31, 2020, the Company received approximately $59 million in direct grant funding and approximately $120 million in accelerated Medicare payments . . .”

Access to Low-Interest-Rate Loan

Air Industries annual report, excerpt from MD&A: “In May 2020, our three operating subsidiaries entered into government subsidized loans with Sterling National Bank in an aggregate principal amount of $2.4 million. Subject to the terms of the note evidencing each loan, each SBA Loan bears interest at a fixed rate of one percent (1%) per annum, with the first six months of interest deferred, has an initial term of two years, and is unsecured and guaranteed by the SBA. At least 60% of the proceeds of each Loan must be used for payroll and payroll-related costs, in accordance with the applicable provisions of the Federal statute authorizing the loan program administered by the SBA and the rules promulgated thereunder.”

Tax Loss Carryback to Years Where They Paid 35%

Air T Inc. annual report, excerpt from income tax note: “The CARES act permits favorable treatment of deductible interest expense as well as the ability to carryback tax losses incurred in the March 31, 2021 fiscal year up to 5 years and recoup previously paid federal income taxes; under which the Company was subject to a higher federal tax rate. The benefit of the recoupment of these taxes are included in these consolidated financial statements and the Company expects to receive a refund of $3.4 million.”

Payroll Tax Deferrals

Tyson Foods Inc. annual report, excerpt from MD&A: “Other long-term liabilities primarily consist of deferred compensation, deferred income, self-insurance and asset retirement obligations. Amount also consists of $134 million of payroll tax deferrals associated with the CARES Act, which we expect will be paid in fiscal 2023.”

Certain Deferred Social Security Payments

Vacasa Inc. quarterly report, excerpt from MD&A: “The CARES Act allows for deferred payment of the employer-paid portion of social security taxes through the end of 2020, with 50% due on December 31, 2021, and the remainder due on December 31, 2022. For the year ended December 31, 2020, we deferred approximately $7.6 million of the employer-paid portion of social security taxes. As of September 30, 2021, and December 31, 2020, the current portion of $3.8 million is included in accrued expenses and other current liabilities and the non-current portion of $3.8 million is included in other long-term liabilities on the condensed consolidated balance sheets.”

Lookback to FASB Government Aid Disclosure Rules

As mentioned above, in 2015 the FASB released proposed Accounting Standards Update 2015-340, Disclosure by Business Entities About Government Aid. On November 17, 2021, it was finalized as Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 832.

The 2015 proposal aimed to:

increase transparency about government assistance arrangements including 1) the types of arrangements,

2) the accounting for government assistance, and 3) their effect on an entity’s financial statements [because] diversity exists in the recognition, measurement, and disclosure of government assistance arrangements because no explicit GAAP exist for government assistance received by business entities.5

As we saw in the recent S&P 500 disclosures, diversity does indeed exist in practice for recognizing, measuring, and disclosing government aid. Unfortunately, the proposed disclosure rule about government aid was not finalized prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, during the disbursal of the most US government aid ever.

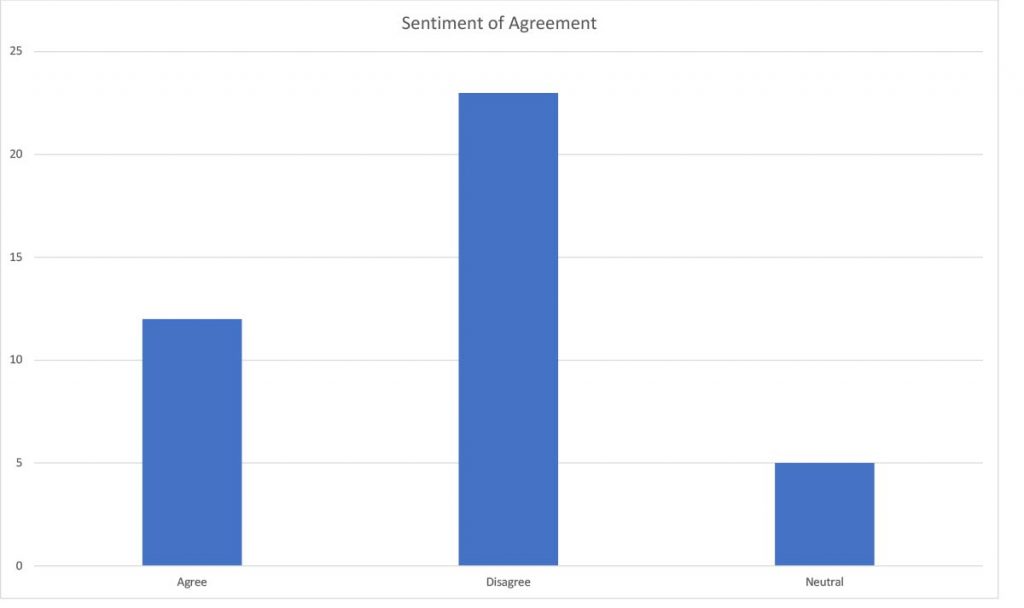

Several factors explain why the proposal did not become final for so long, among them the difficult implementation of other standards governing revenue, lease, and credit loss accounting. However, a big reason the rule lingered in the proposal stage was the large proportion of comment letters concerned with the scope of the proposal, the complexities of implementation, and the lack of systems and controls, among other issues.6 As shown in Figure 4

on the previous page, almost twice as many comments submitted to the FASB disagreed with the proposed standard as supported it.

FASB Final Rule ASC 832: Government Assistance

There we were, without US GAAP rules in the era of the most US government aid ever.

As they say, it is never too late to do the right thing. On November 17, 2021, the FASB released the final rule for government aid disclosures, more than six years after its proposal and near the tail end of pandemic spending. The new rule, codified under ASC 832, requires companies to disclose government aid in ways that account for:

- types of assistance;

- an entity’s accounting for the assistance; and

- the effect of the assistance on an entity’s financial statements.

The main provisions to accomplish the requirements of ASC 832 include:

- information about the nature of the transactions and the related accounting policy used to account for them;

- the line items on the balance sheet and income statement that are affected by the transactions and the amounts applicable to each financial statement line item; and

- significant terms and conditions of the transactions, including commitments and contingencies.7

ASC 832 is effective after December 15, 2021, with early application permitted.

Considerations for Reporting Government Aid

For companies that did not disclose government aid or that seek to amend the way they report government aid, here are some considerations:

- Read ASC 832, Government Assistance, in Accounting Standards Update 2021-10.8

- Establish or refresh accounting policies for government aid in the company’s accounting policy manual. Consider including what thresholds for dollar amounts or for the aid’s significance to the business should trigger reporting. For example, any aid more than $1 million is material and will be disclosed. Or, if the aid is minimal in dollar value, but routine in nature, this may be disclosed.

- If the company currently uses IAS 20 or ASC 958 standards for reporting, consider referencing the new US GAAP rules in ASC 832 in the next round of disclosures.

- Learn and read how organizations currently disclose various forms of government aid in their quarterly and annual financial reports.

- Know your customers, know your suppliers. Taking a play out of Scope 1 and Scope 2 carbon emissions disclosures, in the context of government aid look not only at the government aid you received, but also at the government aid your supply chain or customers have received. Scope 1 disclosures would be government aid received by the entity, whereas Scope 2 is government aid received by a customer or the supply chain. Although Scope 2 government aid may not necessarily be disclosed in financial reports, knowing the government aid received by customers and the supply chain may prove material to your business.

- Know your stakeholders and find out what they deem material and important. Historically this would mostly be the shareholders. However, the receipt of government aid broadens your stakeholders. It is not just the shareholders who matter. Taxpayers foot the bill for government spending, and regulators oversee compliance with GAAP. Do they deserve to know if and how a company is getting their money?

Joseph Bailey is a senior analyst and Todd Cheney is a practice lead at Bloomberg Tax & Accounting.