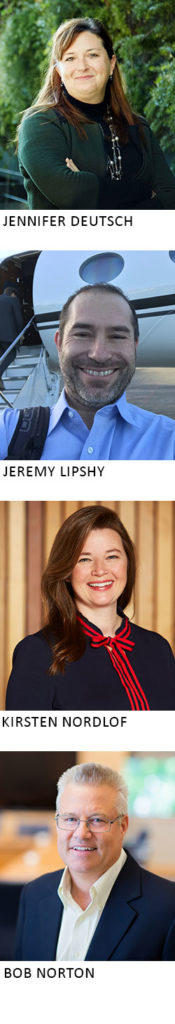

With the passage of the largest overhaul of the tax code in more than three decades, it was axiomatic that the technology used by tax practitioners would be directly impacted. What has that impact been, and what has it meant for in-house tax departments? To answer those questions, we scheduled a roundtable on this topic. We convened a forum in late July comprising Jennifer Deutsch, partner at Deloitte Tax LLP; Jeremy Lipshy, senior vice president for Bausch Health Companies Inc.; Kirsten Nordlof, global head of tax, treasurer, and vice president of finance at Autodesk; and Bob Norton, specialist leader at Deloitte Tax LLP. Deutsch moderated the discussion, which was facilitated by Michael Levin-Epstein, senior editor of Tax Executive.

With the passage of the largest overhaul of the tax code in more than three decades, it was axiomatic that the technology used by tax practitioners would be directly impacted. What has that impact been, and what has it meant for in-house tax departments? To answer those questions, we scheduled a roundtable on this topic. We convened a forum in late July comprising Jennifer Deutsch, partner at Deloitte Tax LLP; Jeremy Lipshy, senior vice president for Bausch Health Companies Inc.; Kirsten Nordlof, global head of tax, treasurer, and vice president of finance at Autodesk; and Bob Norton, specialist leader at Deloitte Tax LLP. Deutsch moderated the discussion, which was facilitated by Michael Levin-Epstein, senior editor of Tax Executive.

Jennifer Deutsch: Right before the call I sent over our premise for the roundtable today. It’s really based on how your companies are approaching what we would call the “operationalization” of tax reform. I think many tax professionals have worked through some initial assessments, and so let’s start with discussing the impact of reform and then try to think about what operational challenges you’re facing. Have you made some decisions, short-term or long-term, on how to address them? What’s driving it?

Kirsten Nordlof: At Autodesk, we were in a unique situation in the sense that we have recently, from the ground up, rebuilt the tax department. So, we didn’t have time to really ramp for tax reform, as our tax planning and provision teams were new, so we just hit the ground running. We built out work papers internally. We had those vetted with various professional accounting firms, and we relied heavily, heavily on spreadsheets. We didn’t have time to build in the automation. So, it’s a spreadsheet-driven model, which has its limitations in scenario planning, because there’s so many different factors at play in tax reform. It is overlaid on top of an already complex provision process. We built out spreadsheet models that we vetted and are strong. It will be nice to have time to automate more of it as we move forward. The second unique factor is, as you know, Jen, we were in the process of designing a new ERP system, so we’re hoping to leverage our new ERP system and have a lot of it built-in and automated as we settle into what our operating model’s going to be post–tax reform. I think as an industry it’s very rare to have the skill set to know how to design a system to be flexible and adaptable, especially when you’re using a new system. We’re going to a cloud ERP system, and we just didn’t have the skill set in-house to really make sure that we got everything we need. Hopefully, designing a new ERP system is only once or twice in our career, right? We don’t want to be doing it every day, so we want to do it right.

Jeremy Lipshy: Please, please—from your lips to God’s ears. It’s funny, because we’re doing that same thing right now. From our end, from an operational perspective, it was a little bit different, just because we were already a Canadian-parented company, and we don’t make an APB 23 assertion. So, we have already been doing E&P calculations, withholding tax calculation estimates and residual U.S. tax liability on our CFCs that we still had underneath the U.S. group. So, a lot of it for us was just modification of that database. We also tried to [automatize] ours—do it through an automation project—so we built this model, so that way we can actually flush the data through on a faster basis and do scenario-analysis planning rather than just in spreadsheets. We linked it with the company’s ten-year model and all of our other FP&A groups so that way we can actually spit something out, if you will, on a very quick basis.

Nordlof: We didn’t have that. I would love to get there, to that situation, but we don’t have that right now. In fact, from a business perspective, we’re going through an interesting time as well. We have a couple big things going on at the same time. We used to be a perpetual license-based company, and we’re in the process of moving to a subscription-based company, so our revenue models are totally different this year than they were two to three years ago. Also, in the U.S. we have—and I assume you have it, too—the ASC 606-605 deferred revenue challenge—

Lipshy: Yes.

Nordlof: So it’s an interesting year to also digest tax reform.

Lipshy: It was the confluence of all events, right? You had different accounting standards, revenue recognition, you had a large tax reform, a short period to do it, all at the same time that both of our companies are going through infrastructure changes. So, we’re looking at doing an ERP implementation at the same time and trying to figure out how it dovetails and how you build the flexibility out. We all would like to explore alternatives to spreadsheets to a certain degree, but when it comes to modeling, when it comes to alternative planning and being nimble as they change rules and give additional guidance, you still have a need for spreadsheet-based models in the interim.

Nordlof: That’s right. For us, from a technology standpoint, we just couldn’t get the IT support, because getting the deferred revenue implementation was so critical from a technology standpoint. Autodesk went live with the new revenue standard in the first quarter we went live with tax reform. There was simply not enough time to build automation.

Deciding on a Strategy

Deutsch: Kirsten, you mentioned you had a lot of internal resources that were tied up. In getting data, how have you changed, or, if you can, comment around making that shift between initial paths and either how you’re planning for additional refinement to the data, or how have you shifted between those two periods? Did you see yourselves refining the models you had more, or are you trying to step back and insert a bit more rigor around it in light of your company’s changes?

Nordlof: On the transition tax, like Jeremy, we only had very limited APB 23 assertion. We had some decent knowledge of what our E&P was. We had engaged an outside service provider two years ago as part of a planning project to do an E&P study on all our material entities. So, we really only had to update that for two years. A lot of our modeling and concern was whether it would be better for the transition tax to use our NOLs or our foreign tax credits. How would we be able to use our foreign tax credits going forward under the new GILTI regime? All these things there is a lot of uncertainty to, so we didn’t spend a lot of time refining our information sources from our internal resources, but more just trying to really understand all the scenarios that we needed to play out and model out. It was more around fact-gathering from a tax perspective.

Lipshy: I think that’s a large part of what we’re doing as well, just calculating the benefit. Is it more beneficial to use a net operating loss, or to pay the transition tax over the eight years? What’s your foreign tax credit situation, OFL, ODL? Doing all different kinds of hypotheticals with various variables—interest deduction, nondeductibility under 163(j)—and doing all of that planning, and trying to understand that it’s not static, that it’s a dynamic calculation, and that there’s puts and calls on all of it. That’s really where we put our focus on it as well.

Nordlof: You just want to make sure that you have all the scenarios that you have to model before you start modeling, which is so numerous it’s mind-boggling.

“I would say that my team’s always evolving. So, we’ve enhanced the tax team significantly, and we have a very strong planning team with people who are as strong as people in the Big Four on a technical level.”

— Kirsten Nordlof

Bob Norton: This is the largest overhaul of the tax code in over thirty years, and the tax planning list of considerations is very long. It sounds like both of you are pretty much focused on scenario planning, thinking about the potential hypotheticals, trying to model it, and thinking less about how to build a sustainable compliance model coming out of that. Is that something that you’ll consider down the road? If you could just talk a little bit to your journey.

Nordlof: I would say on tax reform that’s exactly it. We aren’t in a position yet where we’re even locked in on how we want to treat the transition tax. And then we have, hopefully, knock on wood—although I’m getting less and less sure—some new regulations that will be helpful on our BEAT analysis coming up in November. I thought there was going to be something good. I went out to D.C. with some other technology companies, and I came out of that really upbeat, so to speak, on the BEAT picture, but I had a small update with another technology company who’s really impacted by BEAT, as are we, and they said it wasn’t looking as good. So, I haven’t got any further guidance on that. But I think Treasury said they were going to put something out in November, and we just saw the Tax 2.0 had nothing about it in it, in the synopsis the House released this week. So, we’ll see. But because nothing’s settled yet and we don’t really know how FTCs will be treated, how will BEAT be treated, it’s hard to start thinking about how you are going to operationalize information, because it’s not really clear what information you need yet.

Norton: So, with all that uncertainty, I would imagine just doing the provision is a challenge. How do you guys feel about that?

Nordlof: It is until November, right? For us. I think we have one year. Depending on how flexible your auditor is, you have one year to try to tie everything down, and so it’s one year from December 22, so for us, that is our Q3, so we have to have everything locked down by November. Once November hits and we’ve made our decision, I’m sure we’ll still model it, but we’ll probably try to roll with figuring out how to operationalize and how we’re going to manage it going forward.

Adhering to SAB 118

Norton: Is that a focus now, just adhering to SAB 118?

Lipshy: Yeah.

Deutsch: There’s the data and technology components that we’ve been talking a lot about. There’s also a bit of a skill set flow within the department that you might consider putting under an “operating model” kind of approach. Have either of you started to rethink at all how you’re organized? Whether it’s increased emphasis on needing resources from a U.S. perspective or thinking about your regional teams, have either of you given any thought around that or begun to think about that?

Lipshy: We did, but we did it in a couple of ways. The first thing that we did was create a tax technology group in order to help us design and implement all of the automation to help to do the various scenario planning. That way we could get more of the modeling and the compliance function into an automated system and allow that group to kind of publish it for the rest of the department. We also then centralized the calculations. So, instead of having regional people reporting to a single corporate person who is in charge of doing the entire what I’m going to call the “global APB 23 liability,” including withholding taxes and FIN 48s on withholding taxes, to report that from both a Canadian and a U.S. GAAP, a U.S. tax perspective. So, we took a little bit of autonomy that was more at a regional level and centralized it, so that way it was a single point of contact from both a provision and a compliance perspective. That’s how we approached it.

Nordlof: I would say that my team’s always evolving. So, we’ve enhanced the tax team significantly, and we have a very strong planning team with people who are as strong as people in the Big Four on a technical level. If you see their tax reform printouts, they’re as marked up as they could be; they really are in the weeds on the technical issues and are able to hold their own with our advisors, which gives me a lot of comfort.

Norton: That’s important.

Nordlof: It’s really awesome. It’s great. We also are enhancing—you know, before tax reform, probably a year ago last September, I went on what I would call my “technology quest” to really try to start driving more technology into our team. It’s not just my tax team; it supports all my functions in finance. I hired my first engineer; we’re on the path now to a digital revolution, I would say, and that will, once we get to the other side of tax reform and know what our model looks like—and we are working to get our ERP system up to date—we also have a tax digitalization road map that we’re trying to develop and work to.

Norton: That’s great.

Lipshy: Digital technology revolution—I’m quoting you on that.

Nordlof: And I laughed when you said, “Have you guys thought about your team?” because I actually just, the hour before this call, I spent writing an organization announcement which had a big section in it called “We are digital rising” and naming all the digital people that I am trying to get into roles. It’s superhard; I don’t know, Jeremy, if you find it, but it’s like pulling teeth to push my tax team forward into technology. They just hate using new systems. They would love their spreadsheets; they don’t want to take the time to do something a different way because they’re always crunched and worried about mistakes. So, I’m having to go about it in a different way.

Lipshy: I have a very similar problem. Change management is always difficult. And then, once you’ve made a change, you get the people who continuously do it their old way, so they’re doing two to three times the amount of work that needs to be done. We have that, but that’s in part why I created the tax technology group within our department, to kind of force some of that change. We’ve found a great improvement in our efficiency in our second quarter of implementation on that. So, we’re getting a little bit more buy-in from it, but we’re still having the same issue of people wanting to go back to their tried-and-true or what-they-learned-in-school methods.

Nordlof: I think it’s key when they have to learn the new ERP system anyway, any other kind of technology changes we want to incorporate into the process, that’s a great time, because they won’t have their old way to rely on.

“Change management is always difficult. And then, once you’ve made a change, you get the people who continuously do it their old way, so they’re doing two to three times the amount of work that needs to be done.”

— Jeremy Lipshy

Lipshy: I think that’s one of the reasons to implement a new ERP system. It forces change.

Deutsch: It can be a powerful tool when you may have to tear up everything anyway, right? Because it’s all going to have to change, and now we just layer on the change in regulations and everything else. Jeremy, I’m curious, when we’ve talked about ERP, I’m curious as to whether you have, and maybe could articulate, some of your expectations of software vendors. There’s data-wrangling tools, there’s likely going to be compliance software changes that have to occur. Are you trying to think about what you want technology to do, or are you thinking about it from the standpoint of “What are the vendors going to provide to me?” There are kind of two directions to go.

Lipshy: I personally will never rely solely on vendors to address all the nuances. I think from my methodology and my perspective, the reason why we went with the build-out model we chose was we felt that would get us the most accurate answer. We will then validate that as technology companies and software providers give their solutions. We will be able to use our model basically to validate what they are providing and what assumptions they are making in their calculations.

Norton: Yeah, that’s why you have to test it.

Deutsch: I think it certainly emphasizes the fact that there is likely no generic solution. I think, even just the two different business model changes that both of you are also anticipating, it may be hard to build that into a preprogrammed system, right?

Norton: I agree, Jen. My history is I’ve developed a provision system, and I was at a TEI conference, and one of the panelists asked, “Provision systems have been around now for ten years; how come there hasn’t been that much change in making it easier?” We quickly get to “it’s all about the data.” I guess my point is that some of the vendor solutions are elegant and powerful, but you still have to get the data, the right data. Access via the ERP or, in this case with the GILTI and some of the international tax provisions, even from tax systems, you have to be able to get access quickly to that data to be able to do your planning and what-if analysis. Does that ring true with you guys? How are you feeling about your department’s ability to get the data that they need to be able to monitor their tax positions and these what-if analyses?

Nordlof: I think from Autodesk, our historic system is great. I mean, our historic information is not great, but pretty good. We have a single instance of our ERP system; we have access to it. The reporting maybe isn’t really quick, but it’s not really slow, either; it’s pretty standard. What we struggle with is—and I think this is tax departments across industries—is getting the future-forward information we need to refine our planning models, because there, other finance groups do not need the level of detail tax needs—no one needs to bifurcate different types of royalties, or maybe they do their forecasting by currency or by region but not [by] specific country. Whatever it is they do, they don’t do it at the nuanced level that we need in tax. But I think that’s where the future is going to be really bright for us. In fact, I think with some of the artificial intelligence, easy modules that are coming up, we’ll be able to do some more nuanced artificial intelligence forecasts—machine-learning-type forecasts—on the things that the tax department needs that maybe the FP&A team isn’t going to forecast, but they’re willing to let us dump our historic data into some machine learning and start to get trends that will be a little bit better than “last year’s plus a margin or plus a percent” or whatever.

Norton: Right. Sure.

Lipshy: I just want to say I’m a little jealous since you have a single instance of an ERP, since I have, globally—I think we counted it the other day—fifteen to sixteen ERP systems worldwide.

Nordlof: I had that in my last job, Jeremy, and when I came and interviewed here at Autodesk, the controller told me that and . . . when I had to tell my other CFO why I was leaving, I was like, “Look, they’ve got a single instance of SAP.” And she was like, “Ohhh.”

Lipshy: You mind if I tag along with you? It might be “we come as a team.” For us, it’s interesting, because we face a similar challenge in terms of forecast, especially since we all know that FP&A groups tried to think of business unit or regional rather than legal entities. People don’t, outside of the tax department, really forecast and plan for intercompany transactions, transfer-pricing adjustments and things of that nature, which, of course, Kirsten and I have to do. Especially our planning and our numbers. The other thing for us is because I have over fourteen or fifteen ERP systems, I can’t pull the data that’s on a consolidated basis from each one of those systems and add it up efficiently, so we rely on consolidation tools, which aren’t as granular as we all would like. So, we have to rely on use of estimates as well, which as we hopefully go to a single instance of an ERP system over the next two years, hopefully that can get more granular.

Powerful Systems

Norton: That’s the thing. Some systems are just so powerful now; they can handle the data volumes, and it has the computational power to crank through these more detailed forecasts. If a company chooses to go that route and adopt that type of thing.

Deutsch: We’ve talked a little bit about provision, we’ve talked about some of the calculations —GILTI, BEAT, other things—we talked about operating models. What else has been on your mind or has made you prioritize, or what factors do you think go into prioritizing how much you’re doing? We talked a little bit about new regulations and the timing, but kind of getting a little bit more granular into some of the calculations. I’m curious if there are other decision factors that drove where you put the focus, or particular scenarios, any other items that you think other folks would be interested in, as they try to make their own decisions or other areas that factor into your decision-making?

Lipshy: I can say from my perspective, my personal view rather than, say, my company view, is a factor on what it is that you care about, for example, if it’s a cash tax or if it’s a gap-effective tax rate or non-gap-effective tax rate. Again, we’re a Canadian-parented company, so the impact of your interest expense limitation, the new 163(j), where you put your debt, or where you decide to put intercompany debt, on a global basis became a higher priority a little bit for us, and I would expect many foreign-parented companies are going through that exercise, especially as you add in BEAT, and, like Kirsten said, with GILTI and what the right GILTI rate is with NOLs, etc. That’s really where I think it’s a priority, a focus of what your company is concerned with or focused on, whether it’s a gap rate or a cash tax rate, etc.

Nordlof: I agree. I think by the time your article comes out, Jennifer, nobody’s going to have time to read it and adjust what they’re doing. I would just say if you’re reading this and you haven’t made your decisions yet on what you’re going to prioritize, it’s a little late. [Laughter]

Deutsch: It’s interesting, though. With the multitude of priorities for companies today, it’s challenging to decide what you address now and what you postpone. Jeremy, you commented earlier, we do use application providers or system providers, we’re not depending on them to get all the pieces right. How are you amassing your team, and maybe, if you wouldn’t mind commenting a little bit on what is it that you consider the most in trying to work through what all impact this has, how you get through it, where do you think your team also needs assistance in general? Were you thinking about that?

“There’s data-wrangling tools, there’s likely going to be compliance software changes that have to occur; are you trying to think about what you want technology to do, or are you thinking about it from the standpoint of ‘What are the vendors going to provide to me?’ There are kind of two directions to go.”

— Jennifer Deutsch

Lipshy: I’ll approach it three different ways. The first thing that I thought of is, you have to be comfortable living in the gray. Because, unfortunately, there’s no clear answers on a lot of this stuff. So, for me, when we deal with our auditors and advisors, you get conflicting answers. A lot. Sometimes I just wish I would get consistent answers across the board, but as far as you’re comfortable living in the gray, you know you’re not going to have it. So, for part of my team, that’s a difficult position to be in. They want assurance, and so, as I’ve told my boss and my board, we don’t know the answers. We haven’t gotten guidance on a lot of these things, and even when we do get guidance, we know that there’s going to be interpretations in the future. We don’t know what we don’t know yet, so we’ll give you the information as best as we can and our views of it, but you have to acknowledge and respect that we’re not going to be 100 percent accurate at this time. The one thing I would say from, again, an advisor perspective coming to the company is we appreciate honesty. We appreciate when someone tells us, “Look, we don’t know the answer any more than you do, but this is what we think that it is as a consensus,” rather than “You can do A, then it could be Z,” and it could be something anywhere in between.

Norton: How does your CFO handle that kind of challenge? And your board?

Nordlof: That’s our job, to explain the complex issues in terms that the board and CFO can understand, the areas of grayness and the risks. It is important to bring them along, but also not get lost in the nuances. Be prepared to go deep but stay at the right level. What do you do, Jeremy?

Lipshy: That’s exactly right. There’s two kinds of bosses: there’s the boss that used to do what you did, and you can have a really good understanding and talk with them, and then there’s the ones who have no idea what a tax provision is and are afraid vehemently of it. So, “You got this, Jeremy?” “Yeah.” “OK, good. I’m done.” I’m lucky—my CFO used to do taxes and has done a lot of this stuff, so he gets a lot of the nuance and the unclear guidance. He and I are able to have some really good, frank discussions on it, and then he’s like, “Do what you’ve gotta do, and do what you think’s right.” It’s very appreciative.

Nordlof: It’s the same with my CFO. My CFO has an engineering background, but he has a very blocking-and-tackling manner. I spent a large portion of my career explaining deals to private equity and financial buyers, so it’s just like you sum it down to the risk and the cost and you give ambiguity. You try to give a probability to the unknown—“It’s gray; we’re at sixty percent. You multiply that by the risk number”—and try to quantify it so they have some understanding of the impact of the decisions you’re making. My CFO can get into the weeds when the risk is high, but I need to help him understand when that is necessary.

Lipshy: Yeah, I used to describe the risk profile as, Is the risk a mile deep and an inch across, or is it a mile wide and an inch deep?

“We quickly get to ‘it’s all about the data.’ I guess my point is that some of the vendor solutions are elegant and powerful, but you still have to get the data, the right data.”

— Bob Norton

Deutsch: That’s a tough question. Finally, in retrospect right now, is there anything else that you would have changed about the way you’ve been able to react to tax reform, and if you knew that they were starting to think about significant modifications to what’s out there right now—I know we’re still waiting on regulations and clarifications—but would you change the approach you’ve taken at all, if you could?

Nordlof: I think the modeling is so endless that the speed in which we had to make decisions is almost a blessing, because you could get lost in really wanting to get it, to nail it 100 percent, and I don’t know, with all the different scenarios you can model out, especially when you throw on the factors that I have, where we’re in a U.S. loss now and we’re ramping up to be highly profitable in the U.S. We have different tax rates in different jurisdictions; we’re in the process of negotiating various rulings across the globe. As you layer in all these factors, “OK, what if we get this rate in our ruling in this country, does that impact, do we trigger the high tax?” There’s so many factors that I think we approached it very logically, to the best of our ability, and I like that we have a limit. We can do go-forward planning and change things, but this beginning period, it’s nice to have kind of “OK, we have nine months; now we’re going to have to make a decision to move forward.”

Norton: That’s where the machine learning and the AI might pay some dividends. Of course, that may be a couple years down the road, right, to be able to do all that kind of modeling.

Lipshy: I do agree. I think the speed at which it got and has been enacted was a blessing, because it didn’t allow you to get to paralysis by analysis. It forced you to make quick decisions. Educated decisions, but again, you had to do them quickly rather than six months or longer of analysis. I think that was a little bit of a blessing. I think that we might have taken a few steps to maybe implement more of my automation tools and some of my data gathering a little bit sooner than we did if we had known it was getting passed the way that it did, but that would be the only thing that I would have changed, maybe gone more to automation a little bit sooner.

Nordlof: Since I haven’t automated yet, I can’t say that, but I wish I would’ve automated sooner, too. I still wish we would have automated sooner, but I don’t know if that has anything to do with tax reform.

Deutsch: Thanks for a great conversation.