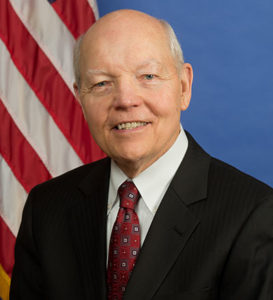

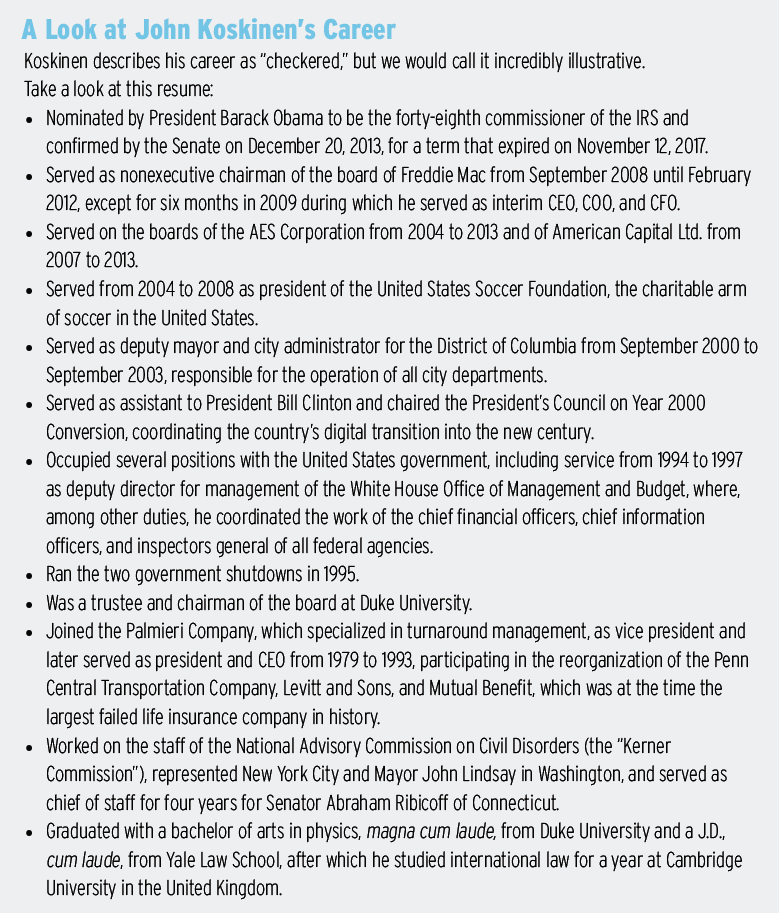

John Koskinen served as IRS commissioner for almost four years before leaving office in November 2017. As IRS commissioner, Koskinen dealt with thorny issues, including antiquated technology, the growing importance of international tax issues, and, of course, budget constraints. Tax Executive was granted one of the first interviews with Koskinen immediately after his tenure ended. Michael Levin-Epstein, senior editor of Tax Executive, conducted the Q&A.

John Koskinen served as IRS commissioner for almost four years before leaving office in November 2017. As IRS commissioner, Koskinen dealt with thorny issues, including antiquated technology, the growing importance of international tax issues, and, of course, budget constraints. Tax Executive was granted one of the first interviews with Koskinen immediately after his tenure ended. Michael Levin-Epstein, senior editor of Tax Executive, conducted the Q&A.

Levin-Epstein: How did your last day as IRS commissioner compare to your first day almost four years ago?

Koskinen: Before my first day almost four years ago, I already had spent time in the three or four months before that preparing for my courtesy calls on the Hill and my confirmation hearing, but mostly to get as much information as I could about the IRS. I interviewed anybody who ran anything at the IRS. So, when I started on my first day, I’d already met all of the senior executives and had already gotten a pretty good idea as to what the major challenges were. The biggest challenge obviously was responding to the congressional requests for the production of documents related to the major dispute about social welfare organizations and how their applications were handled. My last day—my term expired officially on November 12, but my last day in the office was November 9, the Thursday before Veterans Day—was primarily devoted to a farewell gathering in the lobby of the IRS building. There is a theory in management that you should never let anyone know when you’re leaving, because you become a lame duck and they’ll start to ignore you. My experience has been that, if you’re willing to make decisions, people start lining up outside your door trying to get things decided or approved before you leave. That’s been especially true as I left the IRS.

On my last day, we had a two-hour ceremony in the lobby. Jack Lew, who was the Treasury secretary when I started and is an old friend from twenty years ago, was there. Jack and I were deputies together at OMB [the White House Office of Management and Budget] in the mid-nineties in the Clinton administration. Jack was the deputy for budget matters; I was the deputy for management. Tony Reardon, the head of the NTEU, the IRS employee union, spoke as well, along with John Dalrymple, who had been my partner as the deputy commissioner for services and enforcement. Kody Kinsley, the assistant secretary for management at the Treasury Department, represented Secretary [Steven] Mnuchin, who had called me to say he had to be out of town.

So, it was a wonderful occasion. It also gave me a chance to thank all of the employees—there were several hundred crammed into the space—for all of their hard work and the great accomplishments they’d made. They had done this even with the restrictions on our funding and a decline of about 20,000 employees from 2010 until today. My wife, my daughter and her husband, and two of my four grandchildren were there as well. But, after the ceremony, I also spent time signing approvals and authorizations and having a press interview. So, it was a full day. Then, of course, I had to pack up my office and sort through papers for the last time. It was after six by the time I left.

Key Accomplishments

Levin-Epstein: What were your most important accomplishments in your tenure as commissioner?

Koskinen: I always try to make it clear that the agency made great accomplishments, and it was the result of the work of the employees. A lot of times you do get asked, when you finish a tour of duty, “What did you accomplish?” People often say, “Well, I did this and I did that.” I’ve always thought that was a mistake, because the work really is done by the employees. I always tell people I never looked at a filed Form 1040. I never talked to a taxpayer on the phone or in person at one of our taxpayer-assistance centers. I told the employees throughout my four years that I would always recognize that the progress we were making was really progress as a result of their good work. I really do believe that.

Koskinen: I always try to make it clear that the agency made great accomplishments, and it was the result of the work of the employees. A lot of times you do get asked, when you finish a tour of duty, “What did you accomplish?” People often say, “Well, I did this and I did that.” I’ve always thought that was a mistake, because the work really is done by the employees. I always tell people I never looked at a filed Form 1040. I never talked to a taxpayer on the phone or in person at one of our taxpayer-assistance centers. I told the employees throughout my four years that I would always recognize that the progress we were making was really progress as a result of their good work. I really do believe that.

So, the agency, while I was there, with constrained resources, was able to have four very successful filing seasons. During the last filing season, we processed more than 150 million individual returns. I’ve always said that a successful filing season doesn’t happen automatically or by accident—it’s a significant undertaking for the agency. We start preparing for the filing season in May of the preceding year, and, with our antiquated IT system, all of the adjustments and changes that have to be made are a significant challenge. So, the fact that we got through four seasons very smoothly was a high priority for the agency, and a great accomplishment.

We also struggled for a number of years with identity theft and refund fraud. Criminals became increasingly adept at masquerading as a taxpayer because criminals have access to enough personal information to appear as the taxpayer, and then file a false return and claim a refund. When I started, the agency was struggling and basically thought it was doing well if it could hold its own in terms of the number of taxpayers who reported themselves victims of identity theft. We put together a partnership two and a half years ago with the private-sector members of the tax community—tax preparers, tax software developers—as well as the state tax commissioners. We called the partnership the Security Summit. I told them, when we gathered the leaders in Washington in March of 2015, that the purpose of the meeting wasn’t to tell them what to do. The purpose was to form a real partnership and work together to deal with this problem. Increasingly, we were not dealing with entrepreneurs sitting in their bedroom filing false returns. We were dealing with organized crime syndicates around the world. They were well funded, very creative, and very persistent.

At the end of the first filing season, for tax returns for the year 2015 filed in the spring of 2016, we were delighted to find that the number of taxpayers reporting themselves victims of identity theft fell by forty-seven percent. In the next filing season, last year, the number dropped by another forty percent. So, in two years, the number of taxpayers reporting themselves victims of identity theft dropped by almost two thirds. It’s the first time we’ve ever been able to make a dent in the problem. Again, that was the result of a lot of good, ongoing work by IRS employees and a great partnership with the entire tax ecosystem, including financial institutions.

Budgetary Constraints

Levin-Epstein: What effect did budgetary constraints have on a day-to-day basis?

Koskinen: If you look at our budget for 2017, it’s down $900 million from where it was seven years ago in 2010. Over seventy percent of our budget is personnel, so the way we dealt with the declining resources was simply not replacing most people when they left. The result is we’re down 20,000 employees over that seven years. When you take 20,000 employees out of a system, you can become more efficient and effective to counterbalance some of the decline, and we continue to try to do that. But, at some point you begin to interfere with and undermine the ability of the agency to function. So, we have fewer people answering the phone than we would like. The level of service is not at the number that we would like to have it. We have over 7,000 fewer revenue agents, revenue officers, and criminal investigators, so the number of audits we’re doing that need to be done to assure people the system is fair has dropped significantly, by over fifty percent.

We are like every financial institution being attacked by criminals not only trying to file false refunds, but trying to access our database. Thus far we’ve been very fortunate, as a result of all of our security systems and precautions, that nobody’s ever actually accessed the database directly. As noted earlier, some criminals have been very successful at masquerading as individual taxpayers and getting an individual’s tax return, but no one yet has been able to access the database itself. But sixty percent of our hardware is out of date and twenty-two percent of our software is out of date. We’re still running applications that were running when John F. Kennedy was the president.

When you have limited resources, you don’t do enough of anything. You don’t provide the level of service you’d like. You don’t check compliance at the volume you’d like. You don’t upgrade your IT system at the rate you would like. And you have to struggle to maintain security as you go forward.

When I started I told our employees, “If we just guerrilla-war-fight our way through the budget crunch every year and don’t do anything else, we’ll just wake up five or six years later and be that much farther behind.” So, even with our funding and personnel constraints, we worked very hard as an agency to prioritize what we could do and needed to do to upgrade our ability to operate on all fronts.

In particular, our focus was on how could we move our ability to deal with taxpayers forward. The goal has been to give people the opportunity to deal with us online the same way they do today with their financial institutions. They should be able to interact with us digitally, get all the information they need, file their returns, answer questions we have or ask us questions. All this should be able to be done efficiently and effectively online.

We’ve made significant steps toward our future state. You can now check your balance online. You can find out the status of your payments. You can do an online installment agreement. You can do an online offer and compromise, and you could get a copy of last year’s tax return. So, all of that is moving forward at a measured pace, but not as fast as we would like.

“If you look at our budget for 2017, it’s down $900 million from where it was seven years ago in 2010.”

—John Koskinen

At the same time, security has been a high priority. We value the information we have. We have an obligation we take very seriously to ensure that every taxpayer’s account is secure and that criminals don’t have access to it. But it’s a constant balancing act. My farewell tour on the Hill over the last couple of months has been to warn people that you can’t keep cutting the budget without, in effect, threatening the ability of the agency to function. If our budget continues to be cut, it’s not a question of whether the IRS fails. It’s just a question of when. Either the agency will be unable to run the filing season effectively because its IT system doesn’t work, or the compliance rate will begin to decline when people think either everybody’s not paying their fair share or they’re not going to get caught if they cheat or cut corners. As I’ve said, if you lose one percent in the compliance rate, it costs the government $33 billion a year, which dwarfs the amount of money that’s being saved by starving the IRS’ budget.

Other Major Challenges

Levin-Epstein: What other major challenges did you face as commissioner?

Levin-Epstein: What other major challenges did you face as commissioner?

Koskinen: A major challenge was trying to resolve the issue of the so-called targeting of social welfare organizations who had applied for a determination that they were tax exempt, which is why I was asked to take this job. When I started, there was a major battle going on with claims that the IRS had been politicized, that the president and his supporters had instructed the IRS to target conservative groups, to keep them from being able to function. By the time I was confirmed, everyone in the chain of command responsible for that area had been dismissed.

As a result, I ended up spending a significant amount of time for the first couple of years at congressional hearings, which continued to attack the agency generally. House committees attacked our inability to provide documents more quickly—even though we ultimately provided about 1,300,000 pages of documents. They then moved on to attack me personally, challenging my credibility and my integrity. This all came with the territory, but most people said they had never seen anything like it.

Supporting IRS employees and maintaining their morale was a related, very important issue. Federal employees had been under attack for some time. There were shutdowns, pay freezes, and then all the attacks on the IRS as an agency. I’ve always felt that, if you want to know what’s going on in an agency or an organization, go talk to the people who do the work. So, I started in January of 2014, as soon as I arrived, with a series of town halls with frontline employees and their managers all around the country. I went to two cities a week for three and a half months, visiting all of the major IRS offices, and continued to visit offices over the four years. Ultimately I talked to, and listened to, about 24,000 IRS employees. I did that not just to maintain morale, although probably over eighty percent of the frontline employees had never seen an IRS commissioner before, but because that’s the way I was able to keep up with what was actually going on. Wherever I went, and I did over eighty town halls, I always learned something new, either a new issue, a new problem, or something that I thought we had fixed that still was not working well. My town halls were an important part of an ongoing dialogue with employees. I think, as a result, employees felt more and more that they were part of the solution, that their opinions were valued, and that they were playing a critical role in helping the IRS to continue to function, notwithstanding all of the attacks.

Relationship With TEI

Levin-Epstein: What are the major issues facing in-house corporate tax specialists today?

Koskinen: I’ve been delighted to have had the opportunity to talk to TEI members during my term as IRS commissioner. It’s important for IRS executives not only to share their perspectives, but to hear from people “in the real world,” as I called it. This gave us a better understanding of what tax administration looks like from their standpoint. Their questions, concerns, and suggestions were very valuable during my four years.

Clearly, as the global economy gets to be more integrated, the challenges for international corporations are going to get to be more complicated. Increasingly, every company of any size has some connection to the global economy. A major development recently has been the OECD’s base-erosion profit-shifting initiative, focused on what they view as the problem of double nontaxation. That has led to the requirement of significant increases in information exchange with the goal of appropriate taxation. A challenge is that, as you get more aggressive around the world with taxation, you increase the likelihood you’ll have double taxation rather than double nontaxation.

I’m a member of a group called the Forum on Tax Administration (FTA), which is the tax commissioners of the fifty largest countries that operate under the aegis of the OECD. That group, when I first started, had a history of primarily sharing “promising practices”—effective ways of dealing with taxpayers. Every one of those tax commissioners is in the same business, and that is trying to help taxpayers figure out what they owe, how to pay it, and to make sure that everybody is paying their appropriate amount. But, by the time I finished my term as commissioner it had become clear that, as a result of BEPS and all the required information-sharing, tax commissioners around the world were beginning to work much more closely and cooperatively together on international taxation issues.

The United States started the move toward increased information-sharing with passage of the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), which required foreign financial institutions to report to the IRS accounts held by Americans. When I first went to an FTA meeting three years ago in Ireland, I thought, “Well, I’m going to get yelled at by all these people, because we’re making their financial institutions give us information.” But instead I was pleased—and relieved—to find that commissioners were enthusiastic about FATCA because they saw it as the first step toward greater transparency and information-sharing.

Since then, the OECD, under the BEPS program, has developed a common reporting standard, which is really FATCA extended. They have also developed country-by-country reporting requirements for large international corporations. We’re about to start collecting that data from U.S. corporations, and tax administrators around the world will be collecting that data from companies headquartered in their countries. The information will then be shared by host country tax commissioners with every country where the company operates, which protects the company from having to file in each of those countries.

We’re all concerned about making sure that information shared is secure and used appropriately. As we go forward, the greater transparency and collective action has a potential positive upside. In this digital age, as companies get used to filing all of their basic information about where they’re operating, where their employees are, where their revenues are, you could envision companies putting into a central database all of their relevant financial information. Tax commissioners could then access that database and create a tax return and send a bill for taxes owed. The advantage for corporations would be if you’re operating in twenty different countries, rather than having to complete and file twenty different tax returns, you would in effect have one filing. Now, I’m known to be an optimist, which is the only way I could get through all these crazy jobs I have taken. It may take a while to get there, but I think there’s a growing recognition by tax commissioners that double taxation is to be avoided at all costs, that there’s a significant amount of gain from working together to make sure that taxes are appropriately collected, and making sure that disputes are resolved efficiently and effectively. As that happens, I think that major corporations may find that dealing internationally on tax matters will get to be more straightforward, although perhaps not exactly simple. However, if you could ever end up filing a single tax return rather than twenty or thirty or forty of them, life would be a lot easier.

“A major challenge was trying to resolve the issue of the so-called targeting of social welfare organizations who had applied for a determination that they were tax exempt, which is why I was asked to take the job.”

—John Koskinen

Levin-Epstein: What do you think is the biggest issue facing your successor, and what advice do you have for him or her?

Koskinen: The first question is easy for me to answer, and that is the question of budget, of resources. I really do believe that the IRS has been cut back enough that, with the additional responsibilities it has, there is a risk of failure. I’ve already talked with Dave Kautter, who’s been appointed the acting commissioner, about the need for him to make an independent assessment of the funding needs of the IRS. He then needs to make sure that he makes his views clear on the Hill. He already knows enough to understand that the funding constraints are real and a threat that needs to be addressed. My hope is, with the social welfare issues now part of history, and with a new commissioner appointed by this administration, that there will be a rational discussion and understanding about the need for the IRS to have appropriate resources. The irony in all of this is that no one disagrees that, if you give the IRS money, we give you more money back. Whether it’s four, six, or eight times the amount can be questioned, but no one has ever disagreed that we are in fact a significant investment opportunity. We had a proposal for 2017 that said, if you gave us $450 million for enforcement activities, we’d give you back, net of the investment over a ten-year period, $47 billion. There isn’t anyplace else in the government you can go and provide some money up front and get $47 billion back. I think that’s the issue that both Dave Kautter as the acting commissioner and whoever is finally confirmed as the permanent commissioner need to deal with.

My advice to whoever the new commissioner is, is that the IRS has a great workforce. In my forty-five years of dealing with organizations under stress, I’ve never dealt with a better workforce, and clearly never dealt with a better set of senior executives running the organization. I think it’s important for a new commissioner to get to know them and continue to take advantage of and build on the insights, opinions, suggestions, and information that you can obtain by listening to employees at all levels. For a large organization to be agile and quick on its feet, you have to know what’s going on, day in and day out. For that to happen, you’ve got to have effective lines of communication, not only from the top down but, even more important, effective lines of communication from the bottom up. I think that there’s a lot of momentum in that direction at the IRS, and employees have responded very positively. Probably the most important part of any legacy I’ve left behind is that employees continue to feel that they are an integral part of the operation, that their views are important, and the information they have is critical to us as we go forward.