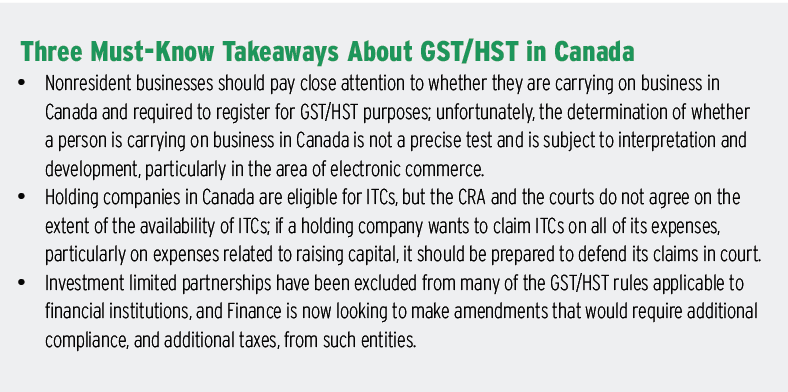

Three recent Canadian goods and services/harmonized sales tax (GST/HST) developments may have significant consequences for and warrant close attention from those engaged in businesses either in Canada or outside Canada with business or financial interests in Canada, as well as their tax advisors.

One of these concerns is whether the Canadian courts have significantly expanded the scope of “carrying on business in Canada” for GST/HST purposes for nonresidents of Canada who have no physical presence in Canada. This issue could have a significant impact on e-commerce.

Another concern is the ongoing tension between the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) and the courts regarding the eligibility of Canadian resident holding companies to claim input tax credits (ITCs) for costs related to their operating subsidiaries in Canada and abroad. For the moment, the courts appear to have the upper hand in broadening such eligibility requirements.

The third development concerns proposed amendments to the Excise Tax Act (Canada), or the ETA, that have implications for nonresident investment limited partnerships in which Canadian investors have an interest. Such partnerships may be required to self-assess GST/HST with respect to their Canadian activities (which would likely not be recoverable as an ITC).

Mandatory GST/HST Registration for Nonresidents

The primary threshold question for determining whether a nonresident of Canada is subject to GST/HST registration and ongoing reporting and remittance obligations is whether the nonresident is “carrying on business in Canada.” The ETA does not define the phrase “carrying on business in Canada” for GST/HST purposes. A “business” is defined broadly to include

a profession, calling, trade, manufacture or undertaking of any kind whatever, whether the activity or undertaking is engaged in for profit, and any activity engaged in on a regular or continuous basis that involves the supply of property by way of lease, licence or similar arrangement, but does not include an office or employment.1

The CRA recognizes, however, that “the mere fact that a nonresident person undertakes an activity that falls within the definition of a ‘business’ does not mean that the business is being carried on in Canada.”2

There is no GST/HST-specific jurisprudence specifically addressing the meaning of the phrase “carrying on business in Canada,” though there is Canadian income tax-related jurisprudence that can be applied, with due regard to the differences between the two tax regimes.3 The CRA’s current administrative policy regarding when a nonresident is carrying on business in Canada for GST/HST purposes consists of twelve factors to be applied in a fact- and context-specific manner. The factors include whether agents or employees of the person are in Canada (and what the length of their stay in Canada is), the place where business contracts are made, and the location of a branch or office, among others.4

The CRA acknowledges that some factors that are relevant for businesses engaged in conventional business transactions may not be applicable to businesses engaged in electronic commerce, where the physical footprint of the business need not be in Canada. The CRA’s guidance regarding e-commerce businesses has generally been that without a physical presence in Canada (e.g., computer servers or employees), the person is not carrying on business in Canada.5

One potential development in this area could significantly expand the scope of “carrying on business in Canada” for GST/HST purposes. In Equustek Solutions Inc. v. Google Inc.,6 the British Columbia Court of Appeal (BCCA) expanded the scope of “carrying on business” in the province for purposes of giving the British Columbia Supreme Court in personam jurisdiction over Google Inc., a nonresident of Canada. Google Inc. had relied on the leading Supreme Court of Canada jurisprudence, which stated that

The notion of carrying on business requires some form of actual, not only virtual, presence in the jurisdiction, such as maintaining an office there or regularly visiting the territory of the particular jurisdiction.7

However, the BCCA, in concluding that Google Inc. was carrying on business in Canada, made the following observations:

While Google does not have servers or offices in the Province and does not have resident staff here, I agree with the chambers judge’s conclusion that key parts of Google’s business are carried on here. The judge concentrated on the advertising aspects of Google’s business in making her findings. In my view, it can also be said that the gathering of information through proprietary web crawler software (“Googlebot”) takes place in British Columbia. This active process of obtaining data that resides in the Province or is the property of individuals in British Columbia is a key part of Google’s business.8

The BCCA’s reasoning originated outside of the tax context (i.e., in the context of the extraterritorial reach of a provincial court); its relevance for GST/HST purposes remains to be seen. If such reasoning were found to be applicable in the GST/HST context, a nonresident internet-based business could potentially be found to be carrying on business in Canada even without a physical presence in Canada, in which case it could be required to register for GST/HST purposes and collect GST/HST on its fees that are charged to Canadian customers.

As a practical matter, one would expect that for reasons of fairness and transparency the CRA should not change its administrative policy regarding nonresident internet-based businesses without providing advance warning to the industry, so this is an issue to monitor, not to act upon, at this time.

Another concern is the ongoing tension between the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) and the courts regarding the eligibility of Canadian resident holding companies to claim input tax credits (ITCs).

ITCs for Holding Companies in Canada

It is generally well-understood that businesses in Canada are eligible to claim ITCs (i.e., refunds of GST/HST that they pay to suppliers in the course of business). However, there is a developing question to what extent parent companies in Canada (i.e., holding companies) with operating subsidiaries in Canada or other jurisdictions are also eligible to claim ITCs in Canada.

Under the general rule in Section 169 of the ETA, an entity must be engaged in a “commercial activity” in order to claim ITCs. Based on these rules, a holding company that merely holds an equity interest in other corporations has no basis to claim ITCs, since its only direct activity is the ownership of financial instruments.

However, for many businesses, the holding company is a useful way to structure ownership of a company for business reasons, as holding companies frequently incur costs (e.g., accounting and legal fees) that relate to the business group as a whole.

Accordingly, Subsection 186(1) of the ETA allows a holding company to claim ITCs in certain circumstances, where the underlying operating company is carrying on commercial activities, by deeming conditions to exist that would permit the holding company to claim ITCs under Section 169.

The extent to which Subsection 186(1) permits a holding company to claim ITCs is currently the matter of some dispute. Subsection 186(1) requires the property or services acquired by the holding company to be “reasonably regarded as having been . . . acquired, imported or brought into the province for consumption or use in relation to shares of the capital stock, or indebtedness” of the related operating company.

The CRA interprets this rule quite narrowly.9 According to the CRA, the expense must relate directly to the shares or indebtedness of the operating company (a “first order of supply”). In the CRA’s example, a holding company that incurs legal and accounting costs to issue shares of its own capital stock (i.e., to raise capital), for purposes of acquiring additional shares in the operating company (or making a loan to the operating company) and thus funding its operations, is not eligible for ITCs on the expenses. The “first order of supply,” according to the CRA, is the issuance of the company’s own shares, which is one step removed from, and therefore not sufficiently related to, the operating company’s shares.

In Stantec Inc. v. The Queen,10 the court considered the CRA’s position that the expenses must relate to the “first order of supply” and rejected it as follows: “The Government contends raising funds by issuing shares is one step removed from obtaining more operating company shares. I see no support for this one step removed doctrine.”

More recently, in Miedzi Copper Corporation v. The Queen,11 the court considered a case where a Canadian holding company owned six mineral exploration companies that operated in Poland, through a wholly owned subsidiary in Luxembourg. The Canadian company raised money through private placements, which it used to finance the exploration projects by way of loan to the Luxembourg company which, in turn, lent the money to the exploration companies. The Canadian parent company had no employees of its own or any office or physical location in Canada. From March 2011 through September 2012, the parent company paid HST in connection with private placement of its shares in the securities market, as well as legal and accounting professional fees. The CRA denied the parent company ITCs on the basis that the expenses did not relate sufficiently closely to the indebtedness or shares of the operating subsidiaries. In response to these facts, the Tax Court of Canada allowed the ITCs, stating that “[S]ubsection 186(1) was intended by Parliament to be a look-through rule and that this purpose would not be served by the narrow reading of the provision suggested by the respondent.”

These decisions (i.e., Stantec and Miedzi Copper) significantly expand the scope of ITC entitlement for holding corporations in Canada, in contrast with the CRA’s narrow position. Unfortunately, both decisions were issued under the Tax Court of Canada’s Informal Procedure, which does not result in a binding precedent. The CRA has not changed its published position, except to state in a published roundtable Q&A session, that in cases with the “same facts” as Stantec and Miedzi Copper, those decisions will be followed.12 This area is continuing to develop as the CRA and the courts continue to disagree regarding the scope of the rule in Subsection 186(1) of the ETA. It remains to be seen how long the CRA will continue to adhere to its administrative guidelines, which the courts appear to have soundly rejected.

Proposed GST/HST Amendments Regarding Investment Limited Partnerships

The Department of Finance (Finance) issued a consultation paper setting out (at a high level) proposed amendments to the ETA on July 22, 2016, that when formally released as draft legislation will have several implications for investment limited partnerships.

Finance proposes to amend the definition of “investment plan” in Subsection 149(5) of the ETA (which is relevant to determining whether such an entity is a listed financial institution) to include investment limited partnerships, which will generally be defined to include a limited partnership whose principal activity is the investing of funds on behalf of a group of investors through the acquisition and disposition of financial instruments (which would include shares of corporations).

Furthermore, Finance proposes to amend the imported supply rules (i.e., services supplied outside Canada to a person resident in Canada) for financial institutions to ensure that nonresident limited partnerships in which Canadians have an interest are required to self-assess GST/HST with respect to their Canadian activities. Finance will do so by making a nonresident limited partnership a “prescribed person” for the purposes of the definition of “qualifying taxpayer” if the total value of the assets of the partnership in which one or more Canadian resident persons has an interest, is equal to or exceeds $10 million, and is equal to or exceeds ten percent of the total value of the assets of the partnership.

Finance has also indicated in the consultation paper that it will introduce a new GST rebate for investment plans (that would include investment limited partnerships) having nonresident unitholders. The rebate would be for the “nonresident investor percentage” of any unrecoverable GST paid or payable by the investment plan in a reporting period. This percentage would be based on the value of the units held by nonresident investors relative to the total value of interests in such investment plan, at a particular time in the fiscal year of the investment plan.

Amending the definition of “investment plan” in Subsection 149(5) of the ETA will mean that investment limited partnerships will be listed financial institutions for GST/HST purposes and hence be subject to the potential application of the selected listed financial institution regime (the SLFI Rules). The SLFI Rules apply to investment plans that have investors situated in an HST province and in at least one other province (either an HST or non-HST province). The SLFI Rules are intended to remove the incentive for an investment plan to locate in GST provinces (and pay only GST on expenses such as management fees), as they require investment plans to calculate and adjust their GST/HST liability based on the residence of their investors, rather than the GST/HST actually paid or payable on input costs.13 For investment plans situated in HST provinces, such plans would be entitled to a refund of the provincial component of the HST paid or payable on input costs, to the extent that such costs are attributable to investors residing outside of HST provinces. This could lead to significant tax relief. The opposite is the case for investment plans situated in GST provinces that pay only GST on input costs. Such plans would be required to pay the additional provincial component of the HST to the extent that such costs are attributable to investors residing in HST provinces.

Amending the imported supply rules to make certain nonresident limited partnerships “prescribed persons” for the definition of “qualifying taxpayer” will require such partnerships to self-assess GST/HST on any amount that is “qualifying consideration” under the cross-border rules. For an amount to be “qualifying consideration” it must be an outlay or expense that, among other things, “may reasonably be regarded as being applicable to a Canadian activity of the qualifying taxpayer.” A “Canadian activity” is further defined in Section 217 of the ETA to mean “an activity of the person carried on, engaged in or conducted in Canada.” As an aside, CRA administrative guidelines indicate that this definition is intended to give the term “Canadian activity” a broad meaning but provide no examples of what constitute “Canadian” versus “non-Canadian” activities.

Investment limited partnerships have been excluded from many of the GST/HST rules applicable to financial institutions, and Finance is now looking to make amendments that would require additional compliance, and additional taxes, from such entities.

This self-assessment obligation could apply to investment advisory service fees payable to nonresident managers by nonresident limited partnerships that are “prescribed persons” for the purposes of the definition of “qualifying taxpayer.” To avoid such self-assessment, the nonresident limited partnership needs to take the position that such expenses are not reasonably applicable to any activity of the investment partnership carried on, engaged in, or conducted in Canada. This position may be available if all of the partnership’s investments are located outside Canada and if the partnership’s management and control are exercised outside Canada by its nonresident general partner. However, this position would be difficult to maintain for any nonresident investment limited partnership engaged in investments in Canada.

It is likely that many nonresident limited partnerships will be unaware of the potential self-assessment requirements that will result from these new amendments. It is also not clear how the CRA will enforce these obligations, given that these partnerships may be outside Canada’s jurisdiction.

The effective date for these proposed amendments to the ETA is unknown (i.e., Finance has not indicated whether they will be retroactive to July 22, 2016, the announcement date of the consultation paper). This date should be clarified when the draft legislation is finally released.

Endnotes

- A “business” is defined more broadly for GST/HST purposes than for Canadian income tax purposes, because unlike for income tax, for GST/HST there is no requirement that a reasonable expectation of profit must exist. Additionally, the law contains a specific reference to supplying property by way of lease, license, or similar arrangement.

- GST/HST Policy Statement P-051R2, “Carrying on Business in Canada” (April 29, 2005).

- See Zen Nimeck and Yola Szubzda, “Carrying on Business in Canada—Income Tax Concepts in a GST World,” 2010 CPA Canada Commodity Tax Symposium Paper.

- The full list of factors can be found in GST/HST Policy Statement P-051R2, supra note 2. In the case of employees performing services in Canada, the CRA has a particularly low threshold for considering the nonresident to be carrying on business in Canada. In example 19 of that policy statement, the CRA considers a nonresident who sends ten employees to Canada for one month to perform a specialized cleaning service to be carrying on business in Canada.

- See GST/HST Technical Information Bulletin B-090, “GST/HST and Electronic Commerce” (July 2002), particularly examples 1 and 2 under the heading “Non-residents Without a Permanent Establishment in Canada.”

- 2015 BCCA 265 (Equustek), appeal to Supreme Court of Canada heard on December 6, 2016, but the decision and reasons were not yet published at the time of this writing.

- Equustek, paragraph 52, citing Club Resorts Ltd. v. Van Breda, 2012 SCC 17.

- Ibid., paragraph 54.

- GST/HST Memorandum 8.6, “Input Tax Credits for Holding Corporations and Corporate Takeovers” (November 14, 2011).

- 2008 TCC 400.

- 2015 TCC 26.

- May 2016 CPA Alberta Roundtable, question 14.

- The HST applies in HST provinces at the following rates: thirteen percent in Ontario and fifteen percent in New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The GST applies in the rest of Canada at the rate of five percent. For the purposes of the SLFI Rules, Québec is treated as an HST province, and the Québec sales tax is treated as the Québec portion of the HST.

Allan Gelkopf, Robert Kreklewich, and Zvi Halpern-Shavim are attorneys at Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP.

Allan Gelkopf, Robert Kreklewich, and Zvi Halpern-Shavim are attorneys at Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP.