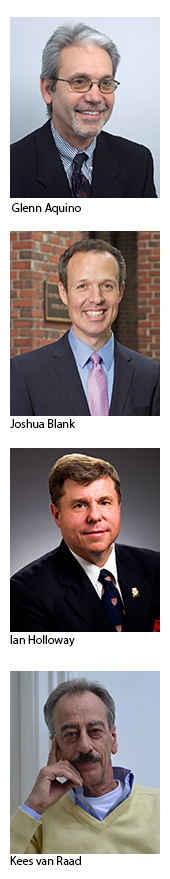

The education of tax professionals has never been as important—or as complex. Tax laws and regulations are proliferating, the international tax scene is burgeoning, online education is on the rise, and, according to some observers, many students expect different educational experiences. In November, we convened a roundtable to explore these issues with a group of international tax educators, including Glenn Aquino, director of the Illinois MS Tax Program, which is based in Chicago and affiliated with the College of Business at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Joshua Blank, professor of tax law, vice dean for technology-enhanced education, and faculty director of the graduate tax program at New York University School of Law; Ian Holloway, professor and dean of law at the University of Calgary in Canada; and Kees van Raad, professor of law at Leiden University and director of the International Tax Center Leiden. Tax Executive Senior Editor Michael Levin-Epstein moderated the roundtable.

The education of tax professionals has never been as important—or as complex. Tax laws and regulations are proliferating, the international tax scene is burgeoning, online education is on the rise, and, according to some observers, many students expect different educational experiences. In November, we convened a roundtable to explore these issues with a group of international tax educators, including Glenn Aquino, director of the Illinois MS Tax Program, which is based in Chicago and affiliated with the College of Business at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; Joshua Blank, professor of tax law, vice dean for technology-enhanced education, and faculty director of the graduate tax program at New York University School of Law; Ian Holloway, professor and dean of law at the University of Calgary in Canada; and Kees van Raad, professor of law at Leiden University and director of the International Tax Center Leiden. Tax Executive Senior Editor Michael Levin-Epstein moderated the roundtable.

Michael Levin-Epstein: How has tax education changed in the last five to ten years?

Glenn Aquino: The way it has changed—I’d say it’s relatively interesting from my perspective, because this program was started eleven years ago. It was started because a lot of the tax practitioners in corporate tax environments, as well as public accounting, were finding that the depth and breadth of tax expertise, or the exposure to various different areas of taxation, was not happening like it did in the past. That’s primarily because the emphasis and focus became more and more on specialization, whether it be multistate taxation, international taxation, etc. So, you have people entering the profession, and they go right into these specialty areas without having the exposure to the more general areas of tax, which, in the past, would provide you a good foundation. In the past, you’d progress from being a generalist to a specialist, and over the course of time it sort of flipped and you became a specialist and needed to get the general background through whatever means were available to you.

Kees van Raad: In the early 1960s, the Dutch government decided to open at the University of Leiden Law School the possibility to specialize in tax law. At that time, law school was five years, with the first three years pretty much the same for all students, and the last two years to be spent on a specialization. To the existing specializations at Leiden University Law School in civil law, public law, criminal law, etc., tax law was added in 1964. As a matter of fact, I was among the thirty or so students that enrolled in that study, to graduate five years later in law with a tax specialization. While those two full years of tax law were pretty comprehensive, at that time international tax was hardly covered. The success of the Leiden University tax program resulted in the 1970s and ’80s in virtually all Dutch universities inaugurating a tax program, sometimes not only in their law school but also in their faculties of economics. In those law school programs tax students would get additional training in accounting, economics, and public finance. And the tax curriculum offered to economics students would include in addition to tax law also quite a bit of general law. So tax graduates from law schools (about eighty percent of those specializing in tax) and from schools of economics (twenty percent) would in the end be quite comparable. Over the years the Dutch universities have delivered annually between 300 and 500 tax graduates—quite a number for a small country like Holland, with only seventeen million inhabitants but a very open and international economy. Occasionally, our tax specialty also increased Dutch exports: in the 1990s when there was a great shortage of tax solicitors in the UK, Dutch tax graduates were lured by major UK firms to move to London to start working there after completing a crash course in UK taxation. After my graduation in tax law in Leiden and an LLM at Georgetown University, I worked for a few years with the Dutch Ministry of Finance before joining Leiden in 1975 as a junior faculty member. I was appointed there in 1986 as a specialized international tax chair, the first of its kind at the time. Over the years, my teaching and research visits to the United States and other countries inspired the idea of creating at Leiden University a specialized international tax program, catering particularly to foreigners from countries with limited or no opportunities for academic training in the international tax area. This resulted in 1998 in the board of the law school of Leiden University accepting my proposal to establish a postgraduate program in international tax under the umbrella of the International Tax Center Leiden (ITC Leiden), which was set up to accommodate the program. This advanced LLM program in international tax law has developed quite successfully over the years, attracting a large number of applications from all over the world, from which we select some forty to fifty students per year. A few years ago an advanced LLM in European tax law was inaugurated, and in 2017 we hope to start a full-year advanced LLM program in transfer pricing for multinational enterprises.

Ian Holloway: I actually think that it’s wrong to consider tax education in isolation from changes that are taking place in legal and professional education generally. What’s happening in law schools—and I assume business schools, too—across North America is a recognition that the old dichotomy between theory and skills is a false one. The best way to impart a deep understanding of principle is to require students to engage with the subject matter in a hands-on way. For obvious reasons, tax law lends itself to this sort of pedagogical innovation. It’s certainly what we’re doing at the University of Calgary, and I know other North American law schools are as well. Beyond pedagogical innovation, what we’re seeing, as Glenn noted, was a recognition that fewer and fewer tax problems are jurisdiction-specific. So we’re all placing a greater premium on international and transnational tax courses. As I often say to students, “jurisdiction” used to be a comfort term for lawyers, for it signified when a problem became someone else’s problem. Now, though, what it signifies is an additional wrinkle. And to the extent that our mission is, as I say all the time, to prepare students for the profession they are joining, not the one we joined, then it is critical that we equip students with the knowledge and skills to respond to those wrinkles.

“I find that today’s students are a bit more focused than we were in my generation.” —Ian Holloway

Joshua Blank: The NYU graduate tax program was started in 1945 and has been educating tax lawyers for over seventy years. To answer your question about the biggest changes that we’ve seen, both at NYU and other LLM programs in the United States, I would say that one of the biggest changes is the format in which these programs are delivered. A significant change at NYU has been that, since 2008, we’ve offered an entirely online LLM program, the Executive LLM in Taxation. The background is that we always heard from applicants who were interested in studying tax at NYU Law but were not in the New York area. They could not necessarily leave their careers to spend a year living in New York in order to participate in our program. Since 2008, we’ve offered basically the same program that we offer on campus, but in an online format. For example, when I teach corporate tax, there are high-definition cameras and a director in the back of the room and at different spots in the room recording the class. Instead of using a chalkboard, I use an electronic smartboard. Instead of having students email questions to me, they post their questions on a discussion board that everyone can see. In addition to the students in the classroom in New York, I have many students who are in the class but who are participating purely in an online format of the class and who are located in another area of the country or the world. At the end of the class, everyone takes the same exam, is graded on the same curve, and the admissions standard for our program for the online students, the Executive LLM in Tax, is the same as the admission standard that we use for our other LLM programs. We’ve seen that there has been a lot of interest among practicing attorneys in our online program. It provides tremendous flexibility in terms of their busy work schedules. As a result of having the online program for lawyers, we received many calls from corporations that have tax departments with lawyers and accountants working side by side. The request that we often received was, “Can our accountants participate in this online tax program that you have?” Historically, we weren’t able to do this because our program was only open to lawyers. However, since 2014, we’ve offered an online tax program for accountants and other financial professionals, which is titled a Master of Studies in Law (MSL) in Taxation. The basic idea is that we are providing the same education that we provide to law students in a pure online format, but the students in this program are accountants who hold a CPA or substantially similar certification, or they have a master’s degree in accounting or tax, and they have at least three years of work experience with U.S. tax issues. We’ve seen a lot of interest from accountants who are working in corporate tax departments and at the major accounting firms. These accountants and financial professionals are interested in taking classes where there is a discussion of judicial doctrine, anti-abuse rules, and general tax policy goals.

Levin-Epstein: Do you charge the same tuition for the online program as you do for in-person classes, and have you had a continual uptick in enrollment?

Blank: Under our current rules, we charge the same tuition on a per-credit basis for all of our tax programs. The big difference, of course, is that online students don’t incur the expense of living in New York for the year and don’t forgo their practice in order to be in New York. We currently have in our Executive LLM in Tax program over 100 students. While online education ten years ago may have been more mysterious to potential employers, today, as so many forms of education have moved online as well as in person, the skepticism that we saw ten years ago has decreased. The MSL in tax for accountants is a new program, so many accountants are not yet aware that we are offering this degree. We have found that many of the students applying to our program have learned about it from other students who are currently in the program. We are anticipating in the future, as students become more aware that we offer this program, applications and enrollment should increase.

Levin-Epstein: Glenn, Kees, and Ian, anything similar at your schools?

Aquino: At this point in time, we don’t have an online complement to our existing program. It’s something that we’re probably going to look at in the near future, but everything that Joshua said about the attractiveness of it is what makes it inevitable. I think all of us at some point in time need to address it and probably be in that game. But what we do have is a program that is designed specifically for working tax professionals. So, we’re looking at people that apply to our program that have two-plus years of either tax experience or financial accounting experience that may be looking to broaden their base in tax or make a career change. It’s an executive-style program, it’s run on Friday afternoons and all day Saturday, and it’s a one-year program. You start in May, and you graduate the following May. It’s thirty-six semester hours of tax courses, and in order to get people in and out of the program in one year, it requires us to have a very specific course curriculum. The maximum class size is thirty-five, and everybody in the class starts at the same time and graduates at the same time. They all take every one of the classes that’s offered in the same sequence—there is no deviation—and we almost have to do that in order to get the people in and out of the program in a year. Again, it was intended and it was structured in that way so that it would be more convenient for working tax professionals to actually sign up and get an advanced degree in taxation.

“International tax has become a greater area of focus in our curriculum.” — Joshua Blank

van Raad: Before we started the advanced LLM program in international tax law in 1998, we had to deal with the issue whether to make the program accessible not only to lawyers but also to accountants and (business) economists with a tax background. Fortunately, the board of the Leiden University Law School accepted our argument that in many countries in the world—and particularly in Asia, the Far East, and in Latin America—tax is practiced mostly by people with an accounting background rather a legal background. If you look at a country like India, it’s probably over ninety percent of the tax work being done by accountants. Also the chambers of the tax tribunals in India—first instance courts for tax matters—are made up of a lawyer and an accountant who will jointly decide on the tax appeals brought to their tribunal. As a result, the Leiden program has been admitting, in addition to law graduates, also economics and accounting graduates with a tax specialization, and with great success: many of our top alumni have an accounting or economics background. Leiden does not offer its programs online yet, but we are looking into that possibility. Being a government university like virtually all Dutch institutes of higher education, there are some legal and bureaucratic hurdles to take, but I’m pretty confident that within two or three years we may be able to offer a parallel online program. One aspect to highlight in this context is that the Leiden program is organized a bit different from the traditional law school curriculums in the Netherlands and elsewhere: we do not have semester-long courses. Courses vary in length (from two to twelve weeks) and are offered sequentially, each concluded with an exam. As a result, a student who is not interested or able to attend the full program may register for a single course (and upon passing the exam of that course, receive a certificate). Further, the Leiden program is a full twelve-month program. We start at the end of August, and students graduate at the end of next August. It’s a very lecture- and workshop-intensive program. Students on the average have about twenty hours of lectures and workshops a week, and that goes on for about forty weeks (with the remainder spent on a thesis), so in the end people may have double the number of hours they would get in similar programs offered elsewhere. As a result, many of our students graduate with at least ten percent less body weight than they had upon arrival in Leiden. Further, some of them who arrived by themselves will leave Leiden with a partner. These special characteristics of the Leiden program may perhaps provide a special incentive for some people to opt for studying tax law at the ITC Leiden.

Holloway: Not yet for us. NYU has been a leader in professional online education in the tax area, and we all have a lot to learn from them. One thing we are working on, though, is a course on cross-border tax issues which brings together virtually students from our school with students at the University of Houston. We’ve got a close partnership with Houston; together we run a really interesting dual-degree scheme called the International Energy Lawyers Program. Students spend two years in each of Calgary and Houston, and earn two law degrees, so that they can be admitted in both countries. Given the interconnectedness of the energy industry, it’s a program that is in significant demand. But reflecting Houston’s strengths in the tax area, we’ve started to work with them on a cross-border tax course, which will be taught jointly to American and Canadian students. We’ll get them to work together in cross-border groups, and to do joint assignments. It’s going to be really exciting.

Levin-Epstein: Have your programs changed recently, and has there been an increase in the number of courses having to do with international tax issues?

Aquino: Our courses have remained relatively static, although obviously the course content changes based on these changes in the tax law. So, something BEPS-related would obviously be covered in our international taxation course. I guess the other thing I’d point out is that our program has a more distinct corporate or business focus, so it’s really geared towards people that are working in consulting firms, whether they be public accounting or tax consulting firms per se, and/or corporate tax department personnel. That’s what our focus is, and that’s the sweet spot for us. I guess I’ll cut it off there.

van Raad: Our program has an international focus throughout its entire twelve-month period. But within the program we continuously monitor changes occurring in the real world. That has led earlier to adding to the transfer pricing course which we have had from the beginning, an advanced transfer pricing course and, ultimately, to the initiative to develop a full-year advanced LLM in transfer pricing program. Similar adjustments we see in other courses. In for example the EU tax course, the topic of state aid is taught in much greater detail these days than in the past.

Blank: First, international tax has become a greater area of focus in our curriculum. We offer a large number of classes on international tax topics. By that I mean U.S. tax rules for international transactions, inbound and outbound. We also offer seminars and other programs on some of the initiatives to attack transfer pricing abuses, such as one on BEPS. But we have heard from employers and our alumni that students should prepare for exposure to international tax issues in any practice area, specifically transactional practice. All of our students take more international tax classes today than they would have a few decades ago. The second area of change is that we have seen an interest among students for what I’ll describe as “deal-oriented courses”—those that don’t just focus on the substantive tax law, but that describe how it’s relevant in practice. We now offer classes like taxation of mergers and acquisitions, taxation of private equity and advanced corporate tax problems. These courses respond, in part, to an interest among employers for their future associates and other employees to have exposure to topics such as inversion transactions, spinoffs, and IPOs. Finally, the last area that’s changed in our curriculum for lawyers is that we’ve introduced courses that give students some exposure to financial accounting concepts. We offer a course called Accounting for Tax Consequences that basically familiarizes our law students with accounting rules that are relevant to tax events and consequences. The course also gives our law students a sense of what accountants will be interested in in terms of the probability that a particular tax position is going to be respected by the taxing authority.

Holloway: Absolutely, for all the reasons I said earlier.

Levin-Epstein: Do you think that the students have changed in important ways in the last ten years or so?

Aquino: I’d say they haven’t changed. The students, again, going back to the comment I made earlier, are students that are looking to expand their depth and breadth of expertise in tax. So, ninety-plus percent of them are tax practitioners, but they’ve been very narrow in their focus in their current positions at their current places of employment, and they’re using our program to expand the breadth and depth of knowledge. Additionally, the students, as well as their current and prospective employers, want to develop into what we call “complete tax professionals” by focusing on skill development in the areas of business communication, teamwork, relationship building, negotiation techniques, and the ethical challenges they will face in practice. We accomplish this in our program via a series of workshops throughout the program year. This helps them to develop into contributing “business” members of the management team, who just happen to have tax expertise. It equips them, whether they are internal or external tax advisors, to function more effectively at the C-suite level.

van Raad: As mentioned earlier, the Leiden tax programs cater primarily to students from foreign countries. As Dutch students interested in tax will typically opt for the tax specialization that virtually all Dutch law schools and schools of economics offer; they are less inclined to take on an additional full year to further specialize in international tax. So we do not have many Dutch students in our program. But as far as the origin of our foreign students is concerned, we’ve seen quite a shift since the beginning of this millennium. This often had to do with students in particular countries becoming—culture-wise—more interested in studying abroad (China, India), sometimes assisted by broad government scholarship programs (Colombia, Indonesia). Globalization certainly has become an important additional factor in many students’ education and career planning.

The three-week programs ITC Leiden runs in various regions of the world certainly cater to this interest. By customizing and adjusting these programs as much as possible to local interests, needs, and skills and offering them in large monolingual areas such as Brazil and the Spanish-speaking Latin-American world in the local language, we try to make a difference.

Holloway: Unlike Glenn, I actually think they have changed a bit. I find that today’s students are a bit more focused than we were in my generation. As with all things, this has good elements and not-so-good ones.

Blank: The first change I think we have observed is that students today do not believe that the only way to learn material in a tax program is in a classroom setting over the course of a fourteen-week semester. Students are much more accepting and interested in the possibility of learning some, or even all, of their course material in an online format as long as there’s an opportunity to interact with the professor and the other students in the class in some way. They’re also not necessarily committed to learning only in a fourteen-week semester, but if it’s possible to learn material over the course of an intensive four-day course or even shorter course, there is a lot of interest among practicing students in that type of format. Each summer, we offer on-campus courses that occur just over a four-day period so that some of our practicing students can travel to New York and be here just for those four days. The second change is that, as I’ve said, we’ve observed there is an interest among tax practitioners who are not lawyers in learning about tax law issues the way that lawyers first learn about them in a classroom. That’s one of the reasons why we offer a program now just for accountants and financial professionals—the MSL in tax. The third change I would say is relatively recent, even just within the last couple of weeks. In the U.S., we’ve just had our presidential election, and now there is one political party in charge of the executive branch and both houses of our Congress. The possibility of fundamental tax reform occurring in the United States is higher than it’s been at any time since 1986. The chance of major tax changes occurring in the United States, specifically with respect to international tax rules and business taxation, within the next few years is high. For decades, we’ve talked about the possibility of fundamental tax reform in largely theoretical terms. As a result of the change in the power structure in Washington D.C., I think many of our prospective students will become aware of the fact that the tax rules may change. This development may be one real advantage of learning about these new rules in the structured environment of an LLM program, whether in person or online. As the rules change, the demand for tax specialists in the United States and abroad will likely grow.

Levin-Epstein: Thank you for an excellent roundtable.