On June 24, with much fanfare, House Republicans laid out the framework of a new tax reform proposal, frequently called a “blueprint” for tax reform. To date, most of the focus of tax reform discussions and the major Congressional committee and Obama administration efforts on tax reform have involved so-called 1986-style reform, that is, modifying the income tax system to lower the tax rates and broaden the tax base in the same manner as the last major tax reform in 1986. Conceptually, the new blueprint represents a significant move away from this 1986 model toward a consumption-based system. Although consumption taxes have their supporters, lawmakers have generally been ambivalent about them,1 and the blueprint makes clear that it does not propose to add a new consumption tax: “Movement toward a consumption-based system need not involve a shift to an explicit consumption tax, such as a retail sales tax, but instead could result from reforms which exclude certain features of the income tax base.”2

Although perhaps not a full-throated endorsement of a consumption tax, the blueprint does represent a shift in the discussion away from simply attempting to replicate 1986 reforms and an elevation of the role of consumption taxes among mainstream tax reform efforts. The cost to reduce rates is astounding: $102 billion over 10 years to reduce the corporate rate by one percentage point and $689 billion over 10 years to reduce the individual rate by one percentage point. However, unlike in 1986, when significant pay-fors, such as the passive activity loss rules and the repeal of the investment tax credit, were available, politically viable pay-fors are more difficult to come by today. That means comprehensive 1986-style tax reform that is revenue neutral will continue to be an uphill battle.

Previous Major Tax Reform Efforts

Congress and the executive branch have been developing tax reform proposals for more than a decade, and many have grown skeptical of the possibility for action in the near future. The rollout materials for the blueprint indicate that the House Ways and Means Committee will begin developing legislation based on the blueprint, with a goal of being ready for legislative action in 2017. Before exploring the blueprint, however, it is helpful to review some of the most recent efforts at tax reform.

Camp Draft

The most recent prior House tax reform proposal, the so-called “Camp Draft,” came from former Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) in February 2014. It is by far the most comprehensive recent proposal and illustrates well the tradeoffs necessary to accomplish a 1986-style revamp of the income tax code. Under the Camp Draft, corporations would be taxed at a top rate of 25 percent. Many of the corporate tax credits and deductions would be modified or eliminated, such as accelerated depreciation, last in, first out (LIFO) accounting, and the domestic production deduction; only a few, like the R&D credit, would be retained. Passthroughs would continue to be taxed through the individual tax system, although domestic manufacturing income would be taxed at a maximum rate of 25 percent.

On the international side, the Camp Draft would move to a territorial system, with a 95 percent exemption for dividends received by U.S. corporations from their foreign subsidiaries. Foreign intangible income would be subject to a 15 percent rate, and previously untaxed foreign earnings would be subject to a one-time tax at 8.75 percent for cash assets and 3.5 percent for other assets. The Camp Draft would also limit net interest expense deductions for U.S. companies with respect to debt with foreign subsidiaries. Specifically, the draft would limit interest deductions based on domestic leverage relative to the worldwide group or a percentage of taxable income.

For individuals, the Camp Draft would create two income tax brackets of 10 percent and 25 percent with an additional 10 percent tax on certain high-income taxpayers. Dividends and capital gains would be taxed at ordinary income tax rates with a 40 percent exclusion from income, resulting in a top rate of 24.8 percent. As with corporate taxes, many individual tax credits and deductions would be modified, reduced, or eliminated. For example, the mortgage interest deduction, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), and the charitable contribution deduction would be scaled back, while the deduction for state and local tax payments would be eliminated.

Senate Working Groups

In the Senate, Chairman Orrin Hatch (R-UT) and Ranking Member Ron Wyden (D-OR) of the Finance Committee formed five bipartisan tax reform working groups, focusing on (1) business income tax, (2) community development and infrastructure, (3) individual tax, (4) international tax, and (5) taxes on savings and investment. Each of the five groups produced a report in July 2015 with options and recommendations for the Finance Committee to consider as it worked toward reforming the tax system.

The report of the Business Income Tax Working Group acknowledged broad support for a substantially lower corporate tax rate, but advised that business tax reform must ensure that passthroughs are not ignored in an effort to reduce the corporate tax rate. The report considered several options to ensure equitable treatment, including (1) a business equivalency rate, (2) targeted tax benefits for passthroughs, and (3) a new deduction for active passthrough business income. The report also urged the committee to further consider corporate integration to eliminate double taxation of corporate income, although it did not recommend a particular approach.3 The Business Income Tax Working Group also discussed ways to promote investment and savings through moving to a consumption tax base.

The report of the International Tax Working Group called for an overhaul of the United States’ current system of international taxation as necessary to stave off additional tax inversions and to prevent base erosion. The report recommended a dividend exemption regime in conjunction with base erosion rules, net interest limitations to stop disproportionate leveraging, and a one-time tax on previously untaxed foreign income. The working group also explored a minimum tax on certain foreign earnings.

Administration Framework and Budget

The White House has focused largely on business tax reform, releasing the Framework for Business Tax Reform in February 2012 (and an update to that framework in April 2016). The framework would lower the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 28 percent while eliminating certain tax expenditures and implementing other reforms. Certain reforms are specifically recommended, such as repealing LIFO accounting and oil and gas preferences, whereas other reforms are offered as part of a “menu of options” to be considered as ways to lower the rate to 28 percent. These options include eliminating accelerated depreciation and creating greater parity between the taxation of corporations and passthroughs (for example, an entity-level tax on large passthroughs). The report also recommends establishing a new minimum tax on foreign earnings (the specifics of which are not described in the report, although it would allow U.S. companies to exclude costs associated with foreign investments, effectively creating a type of territorial system) and a one-time tax on unrepatriated earnings.

The Obama administration’s FY 2014–17 budget proposals have elaborated on the business tax reforms by reserving revenue associated with particular budget proposals for the business tax reform effort. The administration’s budgets also proposed rules to limit the net interest deduction for members of a consolidated group. Specifically, a member’s U.S. interest expense deduction generally would be limited to the member’s interest income plus the member’s proportionate share of the group’s net interest expense, but the rule would not apply to financial services entities. The administration’s budgets have also included proposals focusing on individuals, in particular, increases to the tax rates for high-income individuals, including those for dividends and capital gains, as well as limitations on itemized deductions. In addition, the budgets have proposed enhancements to the EITC, the child tax credit, and the American Opportunity Tax Credit.

Other Tax Reform Proposals

In 2005, President George W. Bush established the President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform with the purpose to provide revenue-neutral tax reform options. The advisory panel, led by Senators Connie Mack (R-FL) and John Breaux (D-LA), recommended two options for reforming the tax code, one of which proposed moving to a consumption-based system. The first option, the Simplified Income Tax Plan, proposed the more traditional path of simplifying the code by eliminating targeted tax breaks and lowering the rates, whereas the second, the Growth and Investment Tax Plan, proposed a consumption-based system not dissimilar from that proposed in the blueprint.4 Other notable tax reform proposals in recent years have mostly focused on income tax reform.

With the endorsement of the leadership of the House of Representatives, the blueprint’s focus on moving to a consumption-based system brings consumption taxes to the center of the tax reform discussion.

As chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, Rep. Charlie Rangel (D-NY) proposed comprehensive tax reform in 2007. Representative Rangel’s proposal would reduce the corporate rate to 30.5 percent and impose a surtax of 4 percent on higher-income households for joint incomes between $200,000 and $500,000 and 4.6 percent for incomes over $500,000. The bill would repeal various tax expenditures, including the domestic manufacturing deduction, and would deny a current deduction associated with deferred foreign income. It also proposed to make permanent the then-temporary small business expensing rules.5

The Bipartisan Tax Fairness and Simplification Act, introduced by Senators Wyden and Dan Coats (R-IN) in 2011 and in similar form by Senator Wyden and former Sen. Judd Gregg (R-NH) in 2010, would reduce the top individual rate to 35 percent and create a flat corporate rate of 24 percent. The legislation would allow immediate expensing for small businesses for all equipment and inventory costs, but would limit accelerated depreciation. It would also reduce the value of the interest deduction by cutting the value of inflation.

In addition, several outside panels have proposed tax reform in recent years. In 2010, President Obama created the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform led by former Sen. Alan Simpson (R-WY) and President Bill Clinton’s chief of staff, Erskine Bowles. As part of a debt reduction plan, the commission recommended establishing a single corporate rate between 23 percent and 29 percent, eliminating all tax expenditures for businesses, and moving to a territorial system. On the individual side, the commission recommended lowering the rates with the top rate not to exceed 29 percent. Capital gains and dividends would be taxed at ordinary rates. Most tax expenditures would be eliminated, though some would be retained or scaled back, including the EITC and child tax credit, mortgage interest deduction, and incentives for employer-provided health insurance, charitable giving, and retirement savings.

Also in 2010, the Bipartisan Policy Center Debt Reduction Task Force, led by former Sen. Pete Domenici (R-NM) and Dr. Alice Rivlin, issued a debt reduction plan that included a proposal for tax reform and then in 2011 a revised plan and tax reform proposal. The revised proposal reduced the corporate rate to a flat 28 percent and the individual rates to 15 percent and 28 percent with no standard deductions or personal exemptions. Capital gains would be taxed as ordinary income (with the first $1,000 excluded). Contributions to retirement accounts would be entitled to a flat 15 percent refundable credit or a deduction up to a maximum of $20,000.

Overview of the Blueprint

In early 2016, newly elected House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) announced that House Republicans intended to lay out “a bold pro-growth policy agenda” this year. To develop this agenda, Speaker Ryan established six task forces charged with developing policy recommendations in each of the following areas: poverty, national security, the economy, the Constitution, health care, and tax reform. Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady (R-TX) led the tax reform task force, and on June 24 the task force unveiled its blueprint for tax reform.

Because the blueprint is a relatively high-level framework for tax reform, the lack of details makes taxpayers’ engagement in the process essential.

The blueprint is a general outline of a tax reform plan and thus lacks many specifics. The blueprint aims to be revenue neutral. To achieve this, while simultaneously providing for the “largest corporate tax rate cut in U.S. history,” the blueprint relies on dynamic scoring and assumes that the remaining extenders are permanently extended so the baseline, or starting point for determining the cost of tax reform, is higher.6 It also assumes the repeal of the tax increases that were enacted by the Affordable Care Act, including the additional 3.8 percent tax on net investment income and the medical device tax. The proposal has not been scored by the Joint Committee on Taxation, however, so the actual cost is not yet known.7

Business Tax Elements

On the business side, the corporate rate would be reduced to 20 percent, and the top rate on passthroughs and other small businesses would be 25 percent. The blueprint would allow 100 percent business expensing for all property except land, resulting in no tax on a new investment. Double taxation on corporate income would be reduced through the reduction in the tax on dividends and capital gains of individual shareholders. Interest expenses would be deductible only against interest income, and net interest expense could be carried forward indefinitely and allowed as a deduction against net interest income in future years. The blueprint explains that immediate expensing of business investments acts as a more neutral substitute for deducting interest on debt incurred to finance that investment. The blueprint contemplates special rules for financial services companies that would take into account the role of interest income and interest expense in that industry. Most business credits and deductions would be eliminated, though the R&D credit and LIFO accounting8 would be retained.

Regarding international taxes, the proposal would move to a territorial system with a 100 percent exemption for dividends from foreign subsidiaries. Accumulated foreign earnings, currently approximately $2 trillion, would be taxed at 8.75 percent for cash and 3.5 percent for other assets (with companies able to pay the resulting tax liability over an eight-year period). It would also provide border adjustments that tax imports but not exports.9 The blueprint states that these provisions (combined with the lower corporate rate) are intended to stop inversions, prevent cash from being “trapped” overseas, and remove incentives to transfer money or businesses out of the country. The proposal would also eliminate the subpart F rules, except for the foreign personal holding company rules that prevent the shifting of passive income to low-tax jurisdictions.

The business provisions of the blueprint draw heavily on two member-sponsored legislative proposals—the American Business Competitiveness Act (the ABC Act, HR 4377) introduced by Rep. Devin Nunes (R-CA) on January 13, 2016, and the Main Street Fairness Act (HR 5076) introduced by Rep. Vern Buchanan (R-FL) on April 27, 2016.

The ABC Act would move to a business consumption tax that taxes all businesses (including passthroughs) on their cash flow at a top rate of 25 percent. The bill would replace business credits and deductions with 100 percent expensing. The bill would also move to a territorial system for international income. The cash flow tax concept in the ABC Act (and as adopted by the blueprint) is similar to the business tax portion of a flat tax.10

Under the Main Street Fairness Act, income earned by passthrough entities that is currently paid by the entity’s owner on their individual tax returns would instead be taxed at the same rates as corporations. While the blueprint proposes a higher rate for passthroughs than for corporations (25 percent vs. 20 percent), it removes passthrough income from the top individual rates, thereby de-linking individual rates and passthrough income. Rather than take the approach of Representative Nunes’ ABC Act to include all passthroughs in the business tax, the blueprint hews more closely to Representative Buchanan’s proposal and explicitly credits its concept on passthrough taxation.11

Individual Tax Elements

On the individual side, the blueprint would reduce the number of tax brackets from seven to three (0 percent/12 percent, 25 percent, and 33 percent) and allow a 50 percent deduction for capital gains, dividends, and interest income. The blueprint would consolidate many basic family tax deductions—the standard deduction, personal and dependency exemptions, child tax credit, and over a dozen education tax benefits—into a larger standard deduction, enhanced child and dependent tax credits, and simplified education tax benefits. The blueprint would eliminate all itemized deductions, except for the deductions for mortgage interest and charitable giving, and repeal the estate tax. The Ways and Means Committee will continue to develop options for encouraging retirement savings.

Consumption Taxes vs. Income Taxes vs. Consumption-Based Taxes

Attention to consumption taxes has been percolating on the periphery of the debate in Congress and in academia, with strong supporters and equally strong detractors. With the endorsement of the leadership of the House of Representatives (including Speaker Ryan and Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady), the blueprint’s focus on moving to a consumption-based system brings consumption taxes to the center of the tax reform discussion.

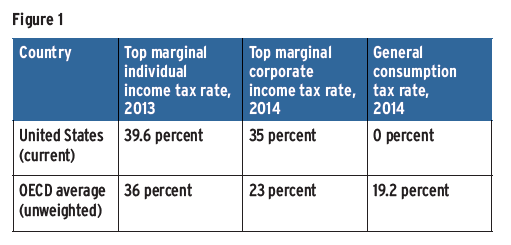

It is commonly noted that other developed nations have a consumption tax in the form of a value-added tax (VAT).12 Indeed, in these other countries, consumption taxes are generally imposed in addition to an income tax, resulting in lower income tax rates. The difference in tax burden is illustrated in Figure 1 comparing the current U.S. tax system with the tax systems of member states in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.13

Consumption taxes have generally been opposed in the United States for various reasons, including concerns about regressivity or concerns that these taxes will be too easy to increase without public accountability.14 When a consumption tax is proposed by U.S. lawmakers, it is generally as a replacement for the current income tax system. The blueprint follows this approach.

National Retail Sales Tax

One type of consumption tax that has been proposed is a national retail sales tax. A sales tax is levied only once, on the retail sale of the final good. The tax is collected by the retailer and remitted to the government. The FairTax (HR 25/S 155), introduced this Congress by Rep. Rob Woodall (R-GA) and Sen. Jerry Moran (R-KS), is an example of a national sales tax proposal. This legislation would replace all income and employment taxes with a 23 percent national retail sales tax. To address concerns that sales tax disproportionately harms lower-income taxpayers who spend a greater portion of their income, the legislation would provide a monthly sales tax rebate (or prebate) intended to offset the amounts paid by families at the poverty line.

Value-Added Tax

More than 140 countries have a VAT, which applies throughout the production chain, based on the value added by a business at each stage of production. This value is computed as the difference between the business’ sales and its purchases of materials from other entities. There are different ways to determine the value added. The credit-invoice method, which is the method of choice in almost all countries that have adopted a VAT, applies the tax rate to the sales price of the good or service and allows a credit for the VAT levied on purchases of taxable goods and services used in the seller’s business. The credit-invoice VAT looks the most like the retail sales tax because it is collected on a transactional basis—small increments of tax are collected at each stage of production—but the total amount should equal the retail sales tax on the sale to consumers.

The subtraction method and the addition method are also ways to determine the value added. The subtraction method differs from the credit-invoice method in that the tax rate is applied to the net of sales less purchases, and the addition method is the mirror image of the subtraction method, applying the tax rate to the sum of the taxpayer’s inputs that are not purchased from other taxpayers (for example, profits, wages, and interest). As a presidential candidate, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) proposed replacing the corporate income tax and payroll taxes with a 16 percent subtraction-method VAT (though he rejected the label, calling it instead a “business flat tax”), and instituting a flat 10 percent individual income tax.

Sen. Ben Cardin (D-MD) has introduced the Progressive Consumption Tax Act (S 3005 in the 113th Congress), which illustrates how a VAT might work with an income tax. Senator Cardin’s legislation would reduce the income tax burden by imposing a 10 percent VAT on goods and services. Under this proposal, the top individual income tax rate would be lowered to 28 percent and the corporate rate to 17 percent. Many individual credits and deductions would be eliminated and replaced with a consumption tax rebate. An income tax exemption of $50,000 for single taxpayers ($100,000 for couples) would exempt most taxpayers from the income tax.

Flat Tax and Other Variants

A so-called flat tax (also called the Hall-Rabushka flat tax after the economists who first developed it) is another form of consumption tax with separate business and individual components. The flat tax differs from the VAT in that, under the flat tax, wages are subtracted from the business’ tax base and the taxes on wages are paid by the individuals. In essence, the VAT tax base is divided in two, with businesses paying tax on their cash flow and individuals paying tax on their wages. (Return on savings and investment is not taxed.)

Flat tax systems have also been proposed in Congress. The Flat Tax Act (HR 1040), introduced by Rep. Michael C. Burgess (R-TX), would allow taxpayers to elect into a flat tax regime with a rate of 19 percent for the first two years and a rate of 17 percent in subsequent years. Similarly, the Simplified, Manageable, and Responsible Tax (SMART) Act (S 929/HR 1824), introduced by Sen. Richard Shelby (R-AL) and Rep. Mike Rogers (R-AL), would replace the current income tax system with a 17 percent rate on wage income for individuals and on cash flow for businesses. As noted earlier, the cash flow tax proposed in Representative Nunes’ ABC Act and in the blueprint are also forms of the business component of a flat tax.

Variants of the flat tax include the X tax, proposed by the late Princeton University economist David F. Bradford. The X tax calls for graduated rates on individual wages, and exemptions and credits could be retained for lower-income households. The business tax would be a flat rate equivalent to the top individual rate. Another variant of the flat tax is a personal expenditure tax (also called a “consumed income” tax). This version most resembles the current income tax system, in that individuals report all their income on tax returns and then claim a deduction for amounts saved or invested. Like the X tax, the personal expenditure tax would include graduated rates and exemptions and credits.

Blueprint

The blueprint stops short of recommending a pure consumption tax and instead characterizes the proposal as a “movement toward a consumption-based system.” The blueprint appears to combine features of several consumption tax models.

On the business side, the corporate income tax would be replaced by a cash flow tax that resembles the business component of the flat tax. Businesses will be able to deduct compensation paid to their employees (the tax on which will be paid by the employees) as well as fully expense their investments. While some tax credits, like the R&D credit, will be retained, businesses will essentially pay tax only on their cash flow. Unlike prior consumption tax proposals, such as those of Representatives Burgess and Nunes, however, the description in the blueprint suggests that passthroughs would continue to be taxed through the individual tax system, albeit at a reduced rate.15 Significantly, however, the blueprint would de-link the tax rate on passthrough income from individual tax rates, a move that addresses a substantial objection that small businesses had in regard to prior tax reform proposals and makes the plan more politically viable.

Perhaps the most significant difference from previous flat tax proposals, however, is the blueprint’s inclusion of border adjustments. Prior flat tax proposals, including Representative Nunes’ ABC Act on which the blueprint’s cash flow tax is based, have not included this feature. Border adjustments are typical in VATs. By including border adjustments, cash flow tax will be applied on a destination basis, meaning that imports would be subject to U.S. tax, but exports would be exempt. Because a VAT in most countries is in addition to an income tax, the benefits of a border adjustment with a cash flow tax are greater than they are with a VAT. A VAT border adjustment provides relief from the VAT but not from income taxes, whereas a cash flow border adjustment provides relief from all tax. This destination-based tax has been described as a game-changer that would eliminate the incentive to move production and profits overseas by reducing the cost of items exported from the United States and increasing the cost of imported items.16

A critical concern about the border adjustments is whether they are compatible with the provisions of the World Trade Organization. WTO rules generally allow border adjustments for indirect taxes like consumption taxes but not on direct taxes like income taxes. The blueprint argues that the proposed cash-flow tax is similar to a VAT and other WTO-permissible indirect taxes and thus should pass muster under WTO rules. Without further details, however, WTO compliance remains an open question.

From the perspective of individual taxes, the blueprint does not move as far toward being a consumption tax as it does on the business side. For individuals, the blueprint most resembles the personal expenditure tax, in that the details provided suggest it would retain the income tax-like format of reporting all income on annual returns and then allowing a deduction for returns on savings and investment. It differs, of course, from a full consumption tax by allowing only a partial deduction on savings and investment. It also appears to contemplate an array of credits and deductions, such as for housing and education, that are not entirely consistent with a pure consumption tax model.

Upon examination of these consumption tax models, the blueprint’s aim of moving “toward a consumption-based approach” becomes clearer. If retail sales taxes and invoice-credit VATs are at the pure consumption tax end, and our existing tax system is closer to the pure income tax end, the blueprint is somewhere in between. Features of the blueprint make it look a lot like a consumption tax, but it does not reach all the way there, particularly in its taxation of individuals. Given lawmakers’ historical ambivalence toward consumption taxes, however, this movement is significant.

Issues to Watch

While the blueprint may announce a shift in approach from a traditional 1986-style reform, many specifics remain to be developed. The Ways and Means Committee has indicated that it will begin developing legislation based on the blueprint, with a goal of being ready for legislative action in 2017. The process contemplates “ongoing dialogue with stakeholders” as the package is crafted.

Because the blueprint is a relatively high-level framework for tax reform, the lack of details makes taxpayers’ engagement in the process essential. For example, how interest income and expenses are defined can make a big difference in the impact of the blueprint’s provisions, as will the special interest expense rules that the blueprint contemplates developing for financial services companies. The treatment of tax-exempt municipal bond interest is also unclear, and the municipal bond groups have expressed concern that the exemption is at risk.17 The real estate industry has concerns as well about the elimination of the interest deduction.18 The blueprint indicates support for robust savings incentives, but the details will still need to be developed, so the impact on retirement and investment products is unknown. Fleshing out the technical aspects of the international tax rules, such as the role of the foreign tax credit, the treatment of branches, and the level of ownership of foreign subsidiaries required for the 100 percent exemption on dividends, will also be important. Similarly, the blueprint suggests that most other tax breaks will be eliminated, but provides no details.

As with any fundamental changes in the tax system, transition rules will be critical. The details of these rules will need careful consideration.

While the blueprint is currently just a high-level framework for tax reform, by putting consumption taxes on the table, it adds another element to the mainstream tax reform debate. As mentioned previously, it was becoming difficult to see how consensus could be achieved using a 1986 model. That said, taxpayers’ participation in the process was familiar, because the 1986 reform focused on rate reductions and retaining beneficial tax provisions without adding new tax burdens. Now, it remains to be seen whether the change in direction to focus on taxing consumption as proposed by the task force will break the logjam on tax reform. In addition, engaging with Congress may be more challenging as the proposals lack details and their effect on various industries is unclear. It will be important for taxpayers to model out the effect of a consumption-based tax to inform them in this new debate

Lisa M. Zarlenga is a partner and Cameron D. Arterton is Of Counsel at Steptoe & Johnson LLP in Washington, D.C.

Endnotes

- Although consumption taxes have been proposed by lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, such as Senators Ted Cruz (R-TX), Rand Paul (R-KY), and Ben Cardin (D-MD) and Rep. Michael Burgess (R-TX), and examined in various tax-reform studies, consumption taxes have been generally politically unpopular in the United States. In 2010, for example, the Senate overwhelmingly passed a measure condemning a VAT as “a massive tax increase that will cripple families on fixed income and only further push back America’s economic recovery.” See Reuven Avi-Yonah, “The Political Pathway: When Will the U.S. Adopt a VAT?” in The VAT Reader: What a Federal Consumption Tax Would Mean for America (Tax Analysts, 2011) at 334; see also Bruce Bartlett, “The Conservative Case for a VAT,” in The VAT Reader: What a Federal Consumption Tax Would Mean for America (Tax Analysts, 2011) at 85 (“As Sen. Byron L. Dorgan, D-ND, said, ‘The last guy to push a VAT isn’t working here anymore’”) and John Harwood, “Momentum Builds to Tax Consumption More, Income Less,” New York Times, November 20, 2015.

- “Savings and Investment Incentives Are Better for Growth,” in A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America, June 24, 2016, p. 15, abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-Tax-PolicyPaper.pdf.

- Senator Hatch is also working on a corporate integration proposal, reportedly involving a dividends-paid deduction.

- As described in the letter from the Advisory Panel to Treasury Secretary John Snow, “The second recommended option, the Growth and Investment Tax Plan, builds on the Simplified Income Tax Plan and adds a major new feature: moving the tax code closer to a system that would not tax families or businesses on their savings or investments. It would allow businesses to expense or write-off their investments immediately. It would lower tax rates, and impose a single, low tax rate on dividends, interest, and capital gains.” Letter to Treasury Secretary John Snow presenting the Report of the President’s Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reform, November 1, 2005.

- The Section 179 small business expensing rules were made permanent in the PATH Act.

- The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act of 2015 and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016 made permanent some previously temporary tax provisions while temporarily extending others.

- Although any estimates are likely to be imprecise given the lack of details, the Tax Foundation has estimated that the blueprint would cost $2.4 trillion over 10 years, but only $191 billion under dynamic scoring. Kyle Pomerleau, “Details and Analysis of the 2016 House Republican Tax Reform Plan,” July 5, 2016 (available at www.taxfoundation.org/article/details-and-analysis-2016-house-republican-tax-reform-plan).

- This seems inconsistent with full expensing, which would presumably include inventory. Perhaps LIFO was intended to be retained as a transition rule, although the blueprint does not discuss any other transition rules.

- Border adjustments are discussed in greater detail in Section III.D. It is uncertain whether these rules will comply with World Trade Organization (WTO) provisions.

- This approach is also similar to that proposed by Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Mike Lee (R-UT) in their Economic Growth and Family Fairness Tax Reform Plan (available at www.lee.senate.gov/public/index.cfm?p=pro-growth-pro-family-tax-reform).

- According to the blueprint, “This approach to the tax treatment of business income will build on concepts developed by Vern Buchanan in his Main Street Fairness Act (HR 5076).” A Better Way: Tax Summary, June 24, 2016, p. 17.

- Kathryn James, “Exploring the Origins and Global Rise of VAT,” in The VAT Reader: What a Federal Consumption Tax Would Mean for America (Tax Analysts, 2011) at 15. As of 2011, over 140 countries had adopted a VAT, and revenue from VAT accounted for approximately 20 percent of worldwide tax revenue. Id.

- Excerpted from Senator Cardin’s explanation of the Progressive Consumption Tax Act (available at www.cardin.senate.gov/pct-faq).

- See e.g., Kathryn James, “Exploring the Origins and Global Rise of VAT,” in The VAT Reader: What a Federal Consumption Tax Would Mean for America (Tax Analysts, 2011) at 20.

- Under the blueprint, the top corporate tax rate would be 20 percent, and the top rate on passthroughs and other small businesses would be 25 percent. Because corporate earnings would still be subject to double tax (although less due to the 50 percent exclusion for dividends and capital gains by individual shareholders), and the passthrough income would be subject to graduated rates up to 25 percent, the effective tax rates are probably much closer.

- Martin Sullivan, “Economic Analysis: Border Adjustments Key to GOP Blueprint’s Cash Flow Tax,” Tax Notes, July 18, 2016. Sullivan, chief economist for Tax Analysts, declared that House Republicans “surprisingly” appear to have hit upon “a magic solution to the challenge of attracting job-creating production into the United States.”

- See Evan Fallor, “House Blueprint for Tax Reform Worries Muni Pros,” The Bond Buyer, June 24, 2016.

- See Stephen K. Cooper, “Some Question Impact of House GOP Tax Reform on Real Estate,” Tax Notes, July 21, 2016.